When I was a boy, we always had bread in our home. My Dad worked as a Deli man most of his life and would bring home beautiful Italian breads that he used to make cold cut and meatball sandwiches. In typical 1950s style, my Mom would keep loaves of white bread in what she called her "All-American house". When we had pasta with "gravy", we'd tear off some bread to use at the end of the meal to clean up the plate. Even when we had meat, like a roast beef, the bread would come out and we'd soak up "the blood" (the drippings) that oozed out of the meat in the bottom of the serving platter. If we had soup or a stew, the bread would work its way to the end of a meal to clean our plates. And if my Mom was making Sunday Gravy, we'd get out the bread, even if all we had was sliced Wonder Bread (ugh), and smear a ladleful of sauce on a slice for a pre-meal snack.  Why scarpetta (little shoe)? Wouldn't it be better to call it scopa (mop)? Little did I know what we were doing was carrying on an Italian tradition in dining--fare la scarpetta (making the slipper/shoe). Scarpetta means shoe in Italian. And to fare la scarpetta a tavola, means tearing off a piece of bread at the table to mop up the sauce or juices left on your plate, help in getting your food onto the fork or spoon. In my father's poor childhood--growing up in a Hoboken tenement with a large family--there weren't enough forks or spoons to go around, so using bread as a scarpetta was a necessity to lift bites of food out of the large communal bowl my grandmother would place in the middle of their table. Nothing goes to waste in Italy, and especially in the impoverished South where my parents came from, one would never leave anything on their plate. Food was life itself. After all, not wasting food is being furbo. And in the South, they don't shy way from having bread with pasta, like they do in the North. What is the preferred type of bread for use as a scarpetta? Curiously, it is ciabatta, which literally means slipper, but any crusty bread will do. Some say that the expression scarpetta comes from the fact that a torn piece of bread looks like a little shoe. I prefer to think that it really refers to wiping your feet... as wiping the bottom of the plate. Because of the extreme poverty suffered by many of our Southern Italian ancestors, others think scarpetta refers to being so hungry that one would eat the soles of their shoes. Sadly, there is historic evidence of desperate people doing just that, so perhaps there is some truth here.  Scarpetta can work with the right OR left hand Scarpetta can work with the right OR left hand However, the tradition of using bread to clean up plates goes back to the time of the Romans. I remember reading in my Latin study book how Romans would use bread after a meal to clean their hands--soaking up the juices and olive oil on their hands--and also cleaning the bowls and the table. They would then pop the soppy bread into their mouths. Again, furbo... nothing is wasted. Fare la scarpetta is an ancient tradition indeed. Perhaps because of its links to Southern culture and Cucina Povera, some areas of Italy consider using a scarpetta bad taste, even though its taste is actually pretty good. Most do it at home or in more casual trattoria and less in more chic ristoranti. But they all do it. And if someone tells you that they don't do it in Tuscany... nonsense. In fact, it's one of the only ways to add flavor to their saltless Tuscan bread. (That stuff is so dry on your palette without salt!) You'd be well served to consider Tuscan bread more of an eating tool, like a spoon or fork, than a bread for eating by itself. You can also do what many Italians do and consider the philosophical meaning of the phrase, fare la scarpetta: Live life fully. Never leave crumbs behind. Soak up everything that life puts in front of you. --Jerry Finzi Focaccia is one of the world's oldest flatbreads with roots in ancient Greece and with the Etruscans, even before the Roman Empire reared its head. The Romans called it panis focacius (bread of the hearth) in Latin. In its basic form, it is a leavened bread, very similar to pizza but without all that cheese. There have been versions of focaccia all through the Mediterranean coastline in Europe and northern Africa. In ancient Roman days, it looked like a very simple, flat round of pull-apart bread. It was a meal to be carried by shepherds and fishermen and meant to be eaten later. In regions of neighboring France it's called fougasse. In Argentina and Brazil--both with large Italian immigrant populations--its name is fugazza and they can be either topped with stringy cheese or even double-crusted and stuffed. The common modern form of focaccia is dimpled with fingertips to make little wells that can hold savory items like olives, cherry tomatoes, peppers, red onion, sliced potatoes, garlic or even sweet things like figs, pear slices, blueberries, walnuts, dates, honey, anise seeds, bulbing fennel (finnocchio), orange zest or grapes. The top is usually brushed or drizzled with extra virgin olive oil and sprinkled with rosemary, sea salt, pepper or other spices. Of course, you can sprinkle a bit of cheese (usually grated), but go to far and you've crossed the line between focaccia and pizza. The variations are endless. In Italy, most pasticceria (pastry shops), panetteria (bread bakery) and even bars will have slices of focaccia often sliced and priced by weight. (Note: A "bar" in Italy is a family friendly place to get cappuccino and pastry in the morning and panini for lunch.) Focaccia is usually baked in 1" deep, dark steel pans. The texture is usually bready and for that reason a high protein "strong" flour (bread flour here in the U.S.) is used. The thickness also has the benefit of being used to make panini, slicing through the middle and stuffing with provolone, mozzarella, prosciutto or thing slices of salami.  Dark, half sheet pan available on Amazon Dark, half sheet pan available on Amazon Ingredients Yeast mixture: 1-3/4 cups warm water (110-115F) 1-1/5 tablespoons fast acting yeast 1 tablespoon honey  For the dough: 1 cup King Arthur all-purpose flour 2-3 cups King Arthur bread flour (plus extra bench flour) 1 tablespoon sugar 1 tablespoon sea salt 2 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil Extra virgin olive oil for the pan Toppings: Extra virgin olive oil (for brushing) Cherry tomatoes 1/4 cup grated cheese (using 1/4 holes/box grater), provolone, asiago, or caciocavallo (cheese is optional) Dried thyme, rosemary, oregano, fresh ground pepper, sea salt Directions Preheat oven to 435F with a pizza stone or steel on the center shelf.

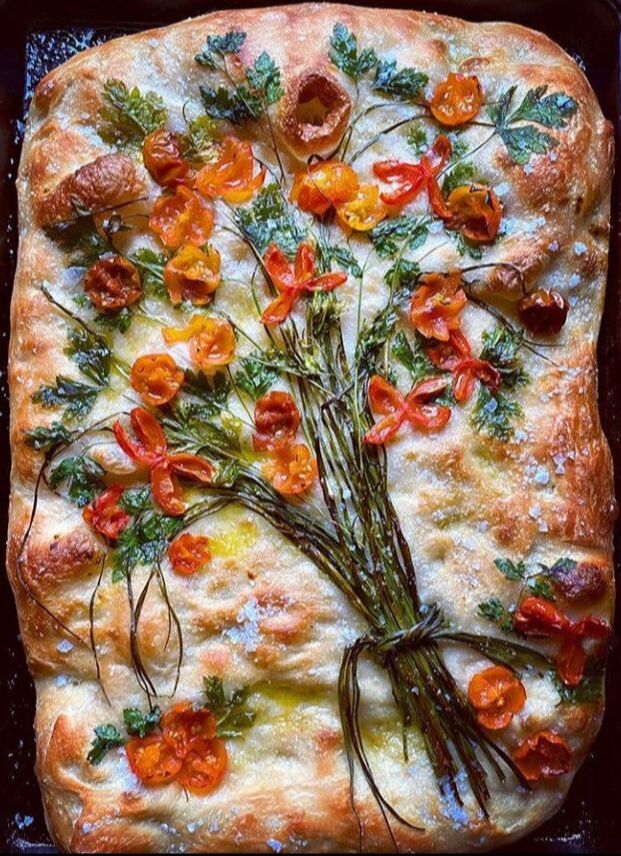

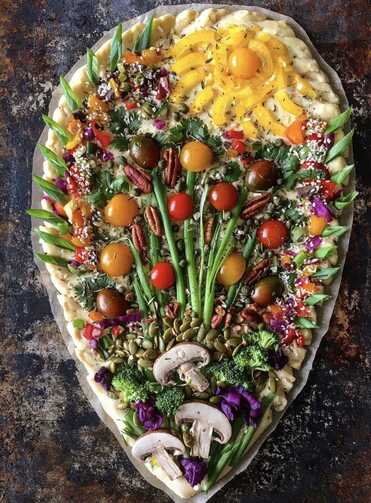

You can reheat in a microwave by wrapping with a damp paper towel, then heating for 30 seconds (time depends on the power of your unit). To kick it up a notch, try a fresh drizzle of extra virgin olive oil (we really recommend unfiltered) or an aged balsamic. For a quick lunch, top with a draping of prosciutto. You can also slice focaccia in half and use to make a panino (sandwich) filled with thin sliced colt cuts and cheese or even cooked ingredients like grilled eggplant, tomatoes and mozzarella or roasted vegetables. Getting Creative Now that you know the basics of making focaccia, consider getting creative, as these examples illustrate. Look for color contrasts, textures and interesting shapes with your choice of toppings. Consider unusual things like asparagus, cauliflower, beets, basil, cilantro, kale, mushrooms, berries, capers, chives, colored course sea salt, and various seeds. Depending on your ingredients, you might have to partially bake your focaccia first with ingredients that can cook during the entire bake time and need to be pressed into the dough. For other things that might burn, like seeds or tender leaves like basil, position on top during later stages of baking. Be creative and make a masterpiece for a special occasion, or simply make simple focaccia for every day snacks and meals... Buon appetito! --Jerry Finzi You might also be interested in...

Forni Italiani: 21 Regional Breads from Italy The Secret Life of Ciabatta Scarpetta: Bread Wipes the Italian Plate Clean Italian Easter Bread: Pane di Pasqua Recipe Pane Coccoi: The Amazing Sardinian Art of Decorated Breads Forno Antico Santa Chiara: More than Just a Bread Bakery Some people called my Dad acting "silly" as a negative, but not me. Anything silly, I love. Something offbeat, oddball, out of the norm, and I'm automatically drawn to it. The time Dad wore vampire teeth at a fancy wedding's cocktail hour was wonderful. My discovery of this interesting pizza is also wonderful: pizza scima ("silly pizza") from the cucina povera traditions of Abruzzo. It's authentic and offbeat. Why is it called "silly"? To understand the name, we have to get into the evolution of the Abruzzese dialect word "scima". This is an unleavened bread, and the Italian word azzimo (masculine) or azzima (feminine) in Italian means unleavened, referring to any bread that's made without yeast. In dialect the word is ascime. Southern Italians tend to shorten words, in this case the word was simplified to scima (SHEE-ma). Scema in Italian can mean either stupid or silly, perhaps in this case referring to someone silly enough to make bread without leavening... The history of this pizza evolved from the 13th century Jews who settled in Abruzzo and made unleavened bread. Traditionally it is baked directly on an open wood fired hearth, common in many country homes even today. After coming up to temperature, the wood coals are cleared to the sides and the dough round is placed directly on the brick base. Next, the dough is covered with a 5" tall dark steel coppo (like a large pot cover) and coal embers are placed on top. This baking method is similar to the Colonial American method of baking bread in a cast iron Dutch oven in an open fireplace. The baking method below tries to mimic the open hearth by baking on a pre-heated pizza stone (to cook the bottom) with a dark pan placed over the top of the pizza (to create a moist, but hot baking environment). You might even try to make this pizza using a baking cloche. Common in the southern towns of Casoli, Roccascalegna, Altino, Lanciano and San Vito Chietino, this pizza is characterized by the addition of extra virgin olive oil and wine. Each year there is even a pizza scima sagra (food festival) in Casoli. Ingredients

Instructions

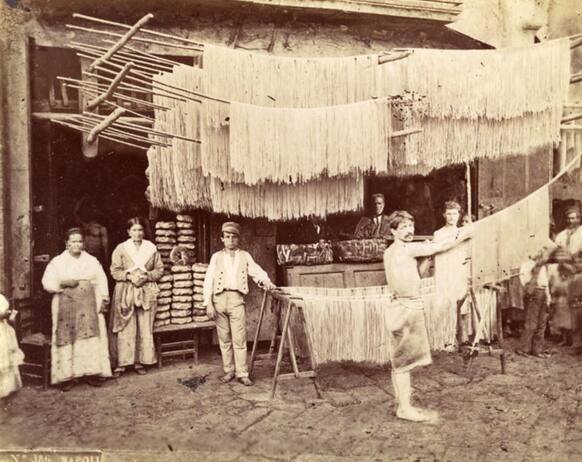

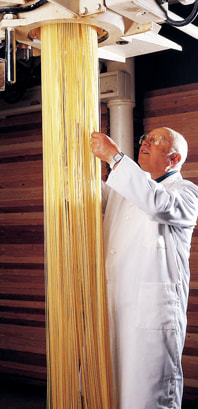

Useful Tools on Amazon... The History of Pasta

Interesting Pasta Facts

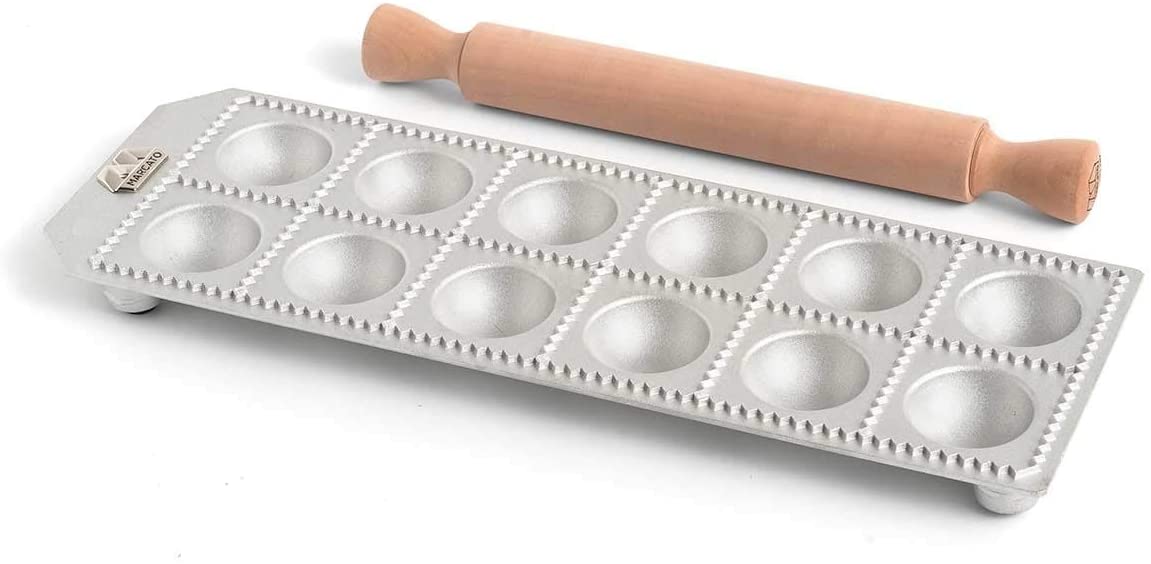

Cooking and Making Pasta

--Jerry Finzi Useful Pasta Tools on Amazon You might also be interested in...

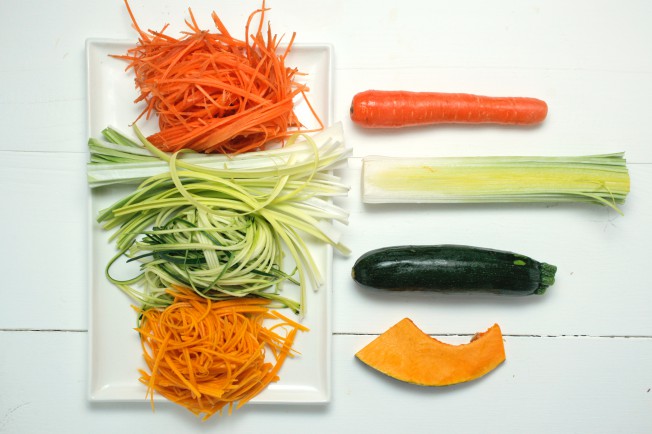

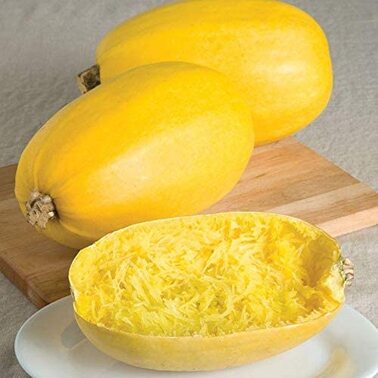

Map of Italian Regional Pastas Corzetti: A Regional Pasta that Really Leaves an Impression Sugo: The "Sunday Gravy" of my Childhood Discover Pallottine from Abruzzo The Light Way to Make Potato Gnocchi The Rarest Pasta in the World - Threads of GodTorta Rigatoni Piede Bolognese al Forno - Baked Standing Rigatoni Pie with Bolognese I'm not a gullible man. Even as a boy, I wasn't one to believe everything I was told. I always asked questions... "Why? Where? When? How?" I read lots of books, including my entire encyclopedia set and my Atlas. I loved science and the arts. I used both sides of my brain. But as a 12-year-old watching the old Jack Parr show in 1963, I tended to to go by the old adage, "Seeing is believing"--especially if you see it on TV! Big mistake! What I saw was a very legitimate sounding short documentary film with a very scholarly, British voice talking about the spaghetti harvest in Switzerland, and mentioning the "tremendous scale of the Italian's... (harvest)" and the "vast spaghetti plantations in the Po valley". From that point on, until I was in my early twenties, I actually believed there was some sort of special tree or bush in Italy that produced some sort of spaghetti... fruit, pod or otherwise. It wasn't until I saw Jack Parr himself talking about the hoax on the Tonight Show in the early 1970s that I learned the embarrassing truth--a "truth" that I would argue about with my non-Italian friends growing up... "Real Italian spaghetti grows on trees!", I would insist. Parr claimed they didn't get a single call about the segment and most people bought it hook, line and sinker. OK, so maybe I was a bit gullible. But it was a very convincing documentary film, produced originally as a serious film for, of all things, a British news show... and besides, I was only 12! On April 1, 1957, on April Fool's Day (Pesce d'Aprile in Italian), the BBC television show Panorama aired the short "documentary" about the "spaghetti harvest" in Ticino, Switzerland, on the border of the Italian Alps. The film shows spaghetti trees ripe with long strands of spaghetti and a farming family harvesting by hand, putting the spaghetti into baskets and then carefully laying them out to dry in the "warm Alpine sun." Some viewers bought it entirely and called BBC to find out where they could buy some of the "real spaghetti". Many British gardeners wanted to know how to buy a spaghetti bush for their own garden. Others were very angry that a joke was portrayed as a serious subject on a real news program. Still others--like me--just tucked this into their knowledge banks, unquestioningly and carried it as a "truth" through at least part of their lives, being even more convinced every time they heard the expression "fresh pasta"... of course, that must be referring to the real stuff fresh picked from the trees! What did I know. After all, neither my Mother or Grandmother made fresh spaghetti, because spaghetti trees probably didn't grow in our climate. All I ever saw growing up was dried, boxed spaghetti--you know, the fake stuff. The following video is the original broadcast in 1957 in England... The following video gives a behind the scenes take on the Spaghetti Hoax story from a member of the Panorama production team who came up with the idea... The next video shows a further chapter of this hoax broadcast in 1967 in Britain explaining how the spaghetti crop was being ruined by a terrible pest--the spag-worm, or "troglodyte pasta". ("Troglodyte" refers to a person so stupid because he lives in a cave). In 1978, San Giorgio Pasta produced a remake of the Spaghetti Hoax for one of their TV ads. Finally, cooking know-it-all, Martha Stewart (I'm not a fan) got into the act in 2009 with her own little spoof about her Spaghetti Bush, "spago officinalis" ("official string") trees.  Italian snake bean seeds on Amazon Italian snake bean seeds on Amazon Well, I've had a lot more culinary education since being misled by that little April Fool's prank when I was young and impressionable: my Mom and Dad taught with every loving dish they put in front of me; Grandma taught me her authenticity; having home and studio in Manhattan for so many years where varied cuisines are around every corner also taught me; In my 30s, I finally learned how to cook from Julia Child, Craig Clairborne, Marcella Hazan, Mary Ann Esposito and Pierre Franey. I now make fresh pasta with my son, Lucas from time to time. And during our Voyage throughout Italy, I never saw a single strand of spaghetti on a bush, tree or vine. Ever. (OK, so I did look, just to be sure.) However, I have since learned that there are actually spaghetti alternatives that grow from Madre Terra. I even grew 2 foot long "snake" beans a few years ago that came pretty close. Here are a few veggie spaghetti alternatives... If you want to make your own, fresh "veggie spaghetti" at home, pick up a Premium Vegetable Spiralizer from Amazon or the attachment we use for our stand mixer, the Kitchenaid Spiralizer Attachment. It's a lot easier than picking the spaghetti from the trees, collecting in baskets and spreading them out in the sun to dry...

(Damn you, Jack Parr and your dry sense of humor!) --Jerry Finzi  Continued from Part 2... Finzi: The first time our family visited Molfetta (where my father was born) we didn’t have time to meet the relatives that still live there (although we've gotten to know each other since on Facebook). What advice would you give to someone with a desire to approach long-lost relatives in Italy, especially if there is a desire to collect the heritage of recipes from their famiglia? Mary Ann: Call or email them; send photos; plan a meeting with them; bring old family photos if you have them. Finzi: When you first met your Italian relatives, what impressed you most? Mary Ann: Their genuine hospitality and love of connection with you. My cousins were especially welcoming. Finzi: I lived in France for a while and tried my best to be a decent French cook, but after experiencing the simplicity of regional Italian cooking on our voyage throughout Italy, I immediately was drawn back my Italian roots. It’s amazing to think that in centuries past, the food eaten by the Italian upper classes was in the French style. Why do you think the Cucina Povera rose to the top of Italian cuisine, with its fairly simple ingredients and basic techniques? Mary Ann: Because that is the true Italian cooking. It was only the upper class Italians who employed chefs called monzu. These were Italians trained in France and what they cooked was truly French and not Italian. Finzi: When my parents got married, according to my mother, she “wanted an American household”, so she didn’t teach her five children Italian. I’ve read that you took lessons on how to speak Italian. Did your mother have this same attitude to “Americanize” your family in this or any other ways? Mary Ann: No, my mother spoke Neapolitan dialect because my Nonna Galasso--her mother--lived with us. My mother would never serve an American style TV dinner and neither would I. Finzi: I’ve never heard you talk about having a second home in Italy. If you do, can you tell us a little about it? And if not, of all the beautiful regions and towns in Italy, where would you love to live, and can you describe your Casa dei Sogni, or Dream Home for us? Mary Ann: I go to Italy every year but do not have a home there; if I did, it would be in Siracusa because I love this baroque town; my second choice would be Torino.  Finzi: Your culinary life was influenced by two Nonne, but not everyone has an Italian grandmother to help educate them on how to prepare Italian dishes. In a way, you have become that Nonna for the millions of us who have watched you cook for nearly 30 years. Can you tell us something about your Mary Ann Esposito Foundation and your desire to pass along your passion and techniques to future Italian chefs? Mary Ann: Thanks for asking! The foundation provides scholarships for students in culinary degree programs in universities offering the study of Italian regional foods and is also establishing a legacy library online to record for posterity, regional recipes that otherwise would be lost to time for future generations. All donations in any amount are most appreciated. Your Grand Voyage Italy readers can go to www.ciaoitalia.com and click on “foundation” to learn more and to make a donation. Finzi: I want to really thank you for taking the time for this wonderful chat, Mary Ann. We'll be looking forward to seeing your new episodes on PBS... my TIVO is fired up to record every episode! One last thought... For us to envision il pranzo perfetto per Maestra Esposito, what are your all-time favorite dinner courses in La Cucina Esposito? Mary Ann:

Guy Esposito on Gardening  Finzi: When I was a boy, my Dad taught me all about saving seeds and the benefits of Home Grown Tomatoes, and now my 15 year old son grows them with me. Our favorites are Eva Purple Ball, Jersey Devil and Giant Belgium. Which are your top three favorite heirloom tomato varieties, and why you like each. Guy: Costoluto Genovese for fresh eating and preserving, intensely flavorful, deep red flesh); San Marzano are the only ones that match to those in Campania for sauce; Redorta for eating fresh, making sauces, canning or drying. It's better than San Marzano for growing in colder climates.  Finzi: For some reason, I’ve always had less than good results with Costoluto in our garden and Redorta is one we haven’t grown. I’ll try some next season. I’m in Zone 6a in Bucks County, Pennsylvania (April 15, last frost) and still I wish the growing season was a bit longer than it is. What are the problems growing vegetables in your short, Zone 5b growing season in New Hampshire? Guy: We get a late start after May 31 because of such a short growing season. Finzi: What do you consider the essential vegetables for an Italian gardener to grow, and for beginners, which do you think are the easiest? Guy: Lettuce, zucchini and radishes are easiest and the hardest are melons and artichokes. Finzi: Were you always a gardener or did your garden develop as Ciao Italia became a more prominent part of your lives as a couple, and what compels you to grow your own vegetables? Guy: I have been gardening since Medical School. We are believers in farm to table food without pesticides. For good health we maintain a Mediterranean diet. Finzi: We are also pretty much organic in our garden, but can always do better with a heathier diet. At least we make pretty much everything from scratch. I just wish we had a good fish monger near us. My wife Lisa would love to grow huge bushes of rosemary like we saw in Italy. For me, pomegranates and olives. But of course, we can’t in our Pennsylvania climate. What don’t (or can’t) you grow in the garden that you wish you could, or would like to grow, and why? Guy: Radicchio di Treviso and Bulbing Fennel (finocchi). Both are delicious for salads or cooking. Finzi: I’ve watched videos on how complicated it is to grow Radicchio di Treviso. Definitely not for the home gardener! What single vegetable or other crop has May Ann wanted you to grow that you haven’t yet, and why haven’t you grown it? Guy: Piennolo del Vesuvio tomatoes. It's just not hot enough here in New England and we have the wrong type of soil. . Finzi: I love the idea of growing these but even if I could, I doubt if they would last through the winter, hanging in large bunches, the way they do in Campania. If you could only grow one, solitary crop, which would you grow? Guy: Lettuce! Virtually every day we eat large salads every day. Finzi: That’s one crop I wish was possible to grow all season long. I’ve grown a variety of types, but some years, the rabbits and chipmunks get the best of them. What are the most difficult things to grow in your garden? Guy: Melons and sometimes tomatoes. Melons need a lot of heat and a long growing season. Some types of tomatoes we love can be prone to disease. Finzi: I’ve also had some experience with melons, but they require a lot of attention and even watering--difficult to keep up with in drier seasons. Is it difficult to be the husband of such a famous chef, or do you consider yourself a partner in Mary Ann’s efforts—and how involved are you in the production of the show? Guy: Mary Ann is first and foremost my wife. I am involved with Ciao Italia as the head gardener and wine consultant. The Mary Ann you see on TV is the exact same person in real life. I am a lucky man! Finzi: You certainly are. Mary Ann and Guy, I want to thank you both for being so generous with your time. I’m certain our readers are going to gain a lot of wisdom from the depth and span of your knowledge, experience and passion about Italian cuisine. Alla prossima e mille grazie! --Jerry Finzi Copyright, 2020 - Jerry Finzi/GrandVoyageItaly.com - All Rights Reserved

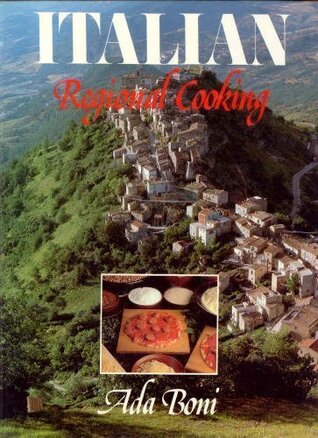

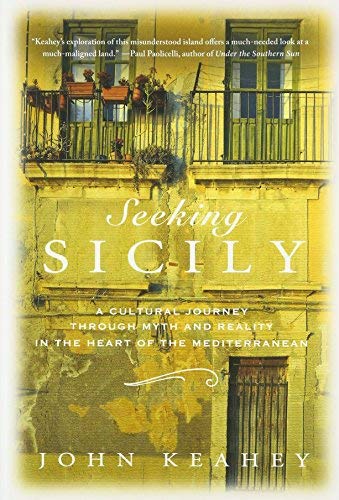

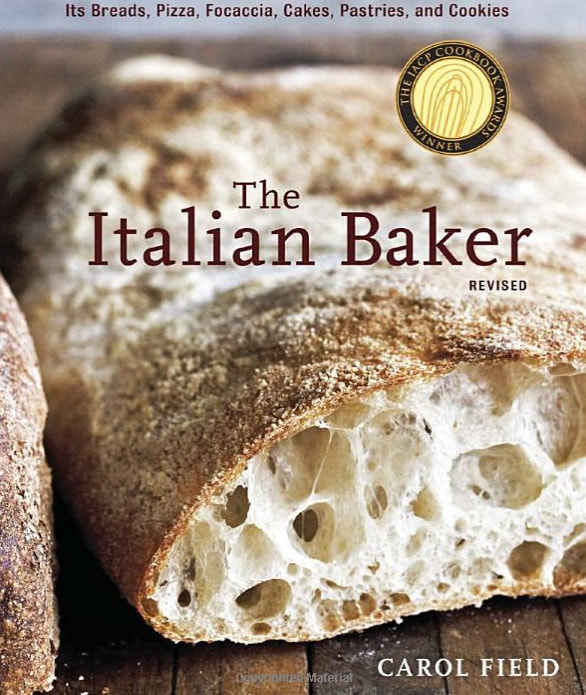

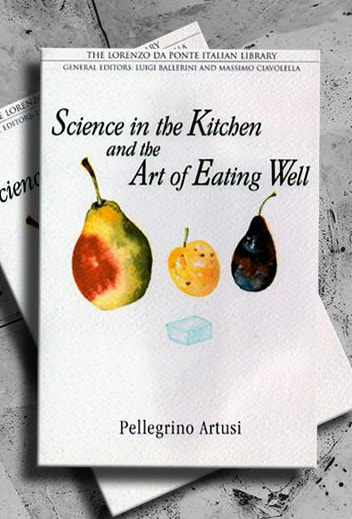

Not to be reproduced in any form without expressed, written permission.  Continued from Part 1... Finzi: Of course, we’ve read your new book, Ciao Italia: My Lifelong Food Adventures in Italy. You've given us all some more great recipes and stories with an enormous degree of detail. Another winner, for sure. Brava, Maestra! Speaking from an Italian-American perspective, what are the main differences between Italian cuisine and the dishes Italian-Americans served here? And regardless of their lack of authenticity, which Italian-American dishes do you really love? Mary Ann: Regional dishes are based on local ingredients, fresh ingredients and simple preparation. Italian-American food is often based on many canned foods like beans and prepared tomato sauces and inferior, imitation cheese. Of course I love spaghetti and meatballs and chicken “parm” like anyone else. Finzi: I grow our own string beans and especially love those yard-long heirloom beans that can plate like a green spaghetti, but I'll have to take your advice and start growing my own beans. We do make our own sauces from scratch, but most of the year used high quality canned tomatoes. In summer we do make fresh tomato sauce, which is wonderful. Chicken “parm” is a favorite in our house, too. We love the way my wife makes it (casserole style with rigatoni) but I also make a lighter version more like a standalone corso secondo. All of us have our favorite cookbooks. We have a collection of yours (of course), but also from Julia Child, Nick Malgieri, Marcella Hazan and Pierre Franey. Which cookbooks couldn’t you live without? Also, what are some historic cookbooks you would recommend for people wanting to explore the history of Italian cuisine? Mary Ann: Ada Boni’s, Italian Cooking; Waverly Root, The Food of Italy; John Keahy, Seeking Sicily; Carol Field, The Italian Baker; Pellegrino Artusi, The Science in the Kitchen and The Art of Eating Well Finzi: We actually have one on your list--Carol Field’s Italian Baker is amazing and includes a fantastic recipe for focaccia. What regions—or towns—have you never visited or cooked in when traveling through Italy? Which are on your bucket list, and why? Mary Ann: I have never cooked in Friuli or Calabria and I would love to cook in Abruzzo because the food is very high quality, and I love the way they use almonds in cooking. Although I love the confetti (candy coated almonds), there is so much more to do with them. Fried Fish Fillets with Parmesan and Almond Coating  Shopping in an Italian market Shopping in an Italian market Finzi: We agree totally. We love the flavor of almonds in all manner of pastries. But to be honest, I personally never went for confetti almonds—I was always worried about breaking a tooth! The waves of Italian Diaspora during the 19th and 20th centuries brought Italian migration to several countries around the world, merging Italian cuisine with that of their host countries. Have you ever thought of exploring the evolution of this mash-up of culinary cultures? (Examples: Brazil, Argentina, Australia, Tunisia). Mary Ann: It is a great idea and I have thought of it. It's on our bucket list! Finzi: I’ll be looking forward to see what you come up with. By the way, in researching my own surname’s roots, I have discovered that there are nearly as many Finzi in Brazil as in Italy! I’m in touch with many of them via Facebook—perhaps I’ll ask them for some fusion Italian-Brazilian family recipes! Are there any other countries you like to visit and cuisines you enjoy cooking? A fusion, perhaps? Mary Ann: I just love Ireland and their food is fantastic. I also enjoy cooking Chinese food. Click the photo above to see our own Shepherd's Pie Recipe  Mary Ann and her Mom cook together in this classic episode. Click to see the video. Mary Ann and her Mom cook together in this classic episode. Click to see the video. Finzi: This past Saint Patrick’s Day, I made my annual shepherd’s pie and my wife Lisa made her Irish Soda bread. Although my wife Lisa makes fantastic Chinese food, she hasn’t picked up her wok in a while. (Hint, hint.) There is such a wealth of ethic food in the world and so many influences in the regional foods of Italy! You’ve cooked with many famous chefs over the years, but we also appreciate when you cook along with home cooks here and in Italy (I still remember the episode with your Mom). Have you thought of doing a series of shows where you feature these home cooks’ recipes? Mary Ann: We have featured many home cooks and you will see them on our new season coming this spring. I learn a lot from them. Finzi: My mother was a pretty good Italian cook and my Dad worked as a grocer and deli man his whole life. Because of this, my favorite heirlooms from them is Mom’s scolapasta, her large pasta pot, her ravioli pin, Dad’s meat slicer and even his retractable crayon marker he used to mark prices on cold cuts. Which kitchen heirlooms do you treasure? Mary Ann: My nonna Saporito’s 2 ft long, thin rolling pin, her cleaver, chitarra, my mother’s scribbled notebooks on Italian foods, her apron and old cannoli forms made out of bamboo. Finzi: Bamboo cannoli forms? I love the idea. Easy to make if you have a neighbor with overgrown patch of bamboo. Beside heirloom kitchen tools, my Mom left me her techniques of making “Sunday gravy”, gnocchi (click for RECIPE) with a fork and her Italian style Pot Roast (click for RECIPE). Dad taught me how to make giant deli meatballs (click for RECIPE) Thanksgiving turkey, Christmas ham and all about home grown heirloom tomatoes. What are the most important technique your family's cooks passed along to you? Mary Ann: Use your hands! They are your best tools. Finzi: According to my son, my pizzas and other dishes are so good that he’d like to see me open a pizzeria or restaurant, but I simply enjoy cooking for my family and friends. With both of your grandmothers cooking for professional reasons, did you ever consider “going pro” and perhaps opening your own restaurant? If “no”, why not? Personally, I would really enjoy dining in your Trattoria Ciao Italia! Mary Ann: No, because I think of my show, Ciao Italia! as my restaurant. Opening a restaurant means a commitment to be there and I cannot do both at the same time. Finzi: Last summer, we vacationed in Cape Ann, Massachusetts and seemed to discover Italian influences just about everywhere. When we visited the North End of Boston we considered it to be a better Little Italy than Manhattan’s Little Italy, the Bronx’s Arthur Avenue or Philly’s Italian Market district. Which “Little Italys” have you visited and what are the best features of each? Mary Ann: I've been to most: Boston, Philadelphia, San Diego, New Orleans. Philadelphia has retained more authenticity; the rest are fading examples. Copyright, 2020 - Jerry Finzi/GrandVoyageItaly.com - All Rights Reserved

Not to be reproduced in any form without expressed, written permission.  Mom with her Big Pots Mom with her Big Pots Long before my mother passed, I would visit her and Dad in their suburban New Jersey home and we would watch Mary Ann Esposito's show, Ciao Italia on their local PBS station. While I learned Mary Ann's recipe and techniques on TV, my mother passed on her own recipes and hands-on lessons in her humble New Jersey kitchen, in the same way her mother had taught her. Mom taught me to make soups first, then stews, then how to make more complex things like light, fluffy gnocchi (I still remember how quickly her arthritic fingers tossed those gnocchi from the ends of a fork). While Mom taught me our own ricette di famiglia Finzi, Mary Ann helped me perfect techniques to help me become a pretty decent, all-around Italian home cook. She also helped me understand that Italian cuisine isn't just one thing... there are many cuisines to be explored in Italy.  Mary Ann's first book holds a place of honor in nostra cucina Mary Ann's first book holds a place of honor in nostra cucina I wanted to have a conversation with Mary Ann in honor of my Mother, since both of these wonderful Italian women have been a strong influence in my own life in my own Cucina. My Mother would be proud to know that I shared a few words with one of our Italian heroines. Mary Ann is the author of 13 books on the art of regional Italian cooking. She has taught millions of fans how to cook authentic, regional, healthy and delicious dishes on her PBS show Ciao Italia, currently in production for its 29th season of episodes! Mary Ann has over 30,000 followers on Facebook and over 1,400 recipes on her Ciao Italia website. She has also made over 40 tours of Italy, 18 of which were organized as cooking classes attended by loyal home cooks.  Mary Ann was gracious in affording me some of her precious time, her schedule made even busier with the recent launch of her new book Ciao Italia: My Lifelong Food Adventures in Italy, as well as her preparing for the 2020 broadcast of her new season of shows on PBS (check your local PBS listings).  So, pour yourself an espresso, sit back and enjoy our conversation. As a bonus, I also discussed gardening with her husband, Dr. Guy Esposito, the official Ciao Italia gardener. --Jerry Finzi Mary Ann learning about Piadina, a flat bread from Emilia-Romagna Our Conversation...  Mary Ann in love with a vintage Capri taxi Mary Ann in love with a vintage Capri taxi Finzi: You’ve been on PBS continuously for 29 years… certainly an achievement for any TV cooking show. Can you explain your commitment to PBS and if you’ve ever been approached to do a show on a commercial cooking network? If you were offered a show, why didn’t you take the offer? Mary Ann: I wanted to have a personal connection with my audience without interruption or distraction and I wanted it to be my show in my words without someone else telling me how to do it. It would have been so much easier to go to go the commercial route but I had higher goals. Finzi: I see your point, Mary Ann. They might have re-packaged what you were bringing to the table (excuse the pun) and your menus might have been someone else’s choices, perhaps by committee. We’re happy you followed your own path. Certainly for my family, some of our favorite episodes have included location segments filmed in Italy. Does your new season include any Italian segments? And throughout the history of your voyages, where were your favorite places to explore—and cook? Mary Ann: Location shoots require a huge effort and lots of money but when our budget allows, we are in Italy. This year for our new season, we will be filming in Tuscany in the fall. All the regions are my favorite, but I am partial to Sicily and Campania.  Mary Ann's Raspberry Tart Mary Ann's Raspberry Tart Finzi: I agree with you on this. There's something so warm and welcoming in the South--a much slower pace. For me, I felt most at home when visiting Puglia where my father was born. The people's welcoming smiles reminded me of him. Some of my other favorite Ciao Italia episodes had you baking with the amazing pastry chef, Nick Malgieri. We love Nick because he was kind enough years ago to help me find the recipe for “pas-ah-chut”, as my Molfettese father called them (pasticiotti). What are your favorite pastries to make? Mary Ann: Of course I love to make cannoli, fruit tarts, lots of different biscotti. Finzi: My thing is making the Crostata di Frutta in our cucina, but my wife is the go-to gal for all sorts of cookies, cakes and pies. Happily, this year she is exploring the world of the twice-baked dolci—biscotti. I've always loved pizza and even worked at our local pizzeria for a while when I was a teen, and for nearly 20 years and I've become a fairly decent pizzaiolo at home. I’ve made Neapolitan, Chicago and Detroit deep dish, “grandma’s”, sfincione, focaccia, thin crust, etc. I think I’ve saved every one of your pizza episodes on my DVR. Which is your favorite pizza and what do you think makes it so special? Mary Ann: I would have to say Margherita is my favorite but I love making all kinds. The important thing is to use as close to original ingredients as possible like Caputo flour for the dough, real mozzarella di Bufala and fresh basil. Finzi: Happily, home gardens, farmers markets and the Farm to Table movement are growing in popularity. Living in the country, we often have to travel to Philadelphia or New York to get precious ingredients like mozzarella di Bufala, but we do grow our own veggies and lots of basil! For me, baking pastry is very specific and precise, which is perhaps why my wife does that in our house. What are your thoughts on “cooking to the recipe” versus cooking the way nonne do, by taste, look and feel? Mary Ann: I’m with you; I never cook with recipes even though I write books with precise recipes for readers based on my testing them. I think the best cooks are those who improvise. Finzi: In my case, improvisation can make it a little difficult when I want to share one of my recipes with our GVI readers. I have to convert a pinch, a dollop, a handful, a splash or to describe how a dough should look and feel. What I’ve always loved about your cooking is the historic and anthropological perspective you bring into the Italian kitchen. You teach that “Italian food” doesn’t really exist, but it’s really about the 20 different regional cuisines of Italy. What would you like to see as an effort to change the American view of “Italian food” as only being pizza, chicken “parm” or spaghetti and meatballs? Mary Ann: Watch my show! Read things about regional cooking; in my just released new book CIAO ITALIA (My LIFELONG FOOD ADVENTURES IN ITALY) you will find a treasure trove of regional recipes with stories that support their origin. Copyright, 2020 - Jerry Finzi/GrandVoyageItaly.com - All Rights Reserved

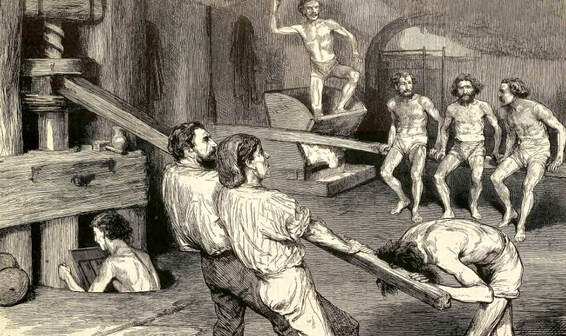

Not to be reproduced in any form without expressed, written permission.  One of the cucina povera (poor kitchen) Christmas traditions in Italy is Polenta alla Spianatora (polenta on the board), a rustic meal of polenta served as a dinner during the cold nights between la Vigilia (Christmas Eve) and Capodanno (New Year's Day). What makes this meal so unusual is the manner in which it is served. In the old days, hot polenta was poured and spread out directly on the family's wooden table. A slow-cooked sugo (thick, meaty tomato sauce), peas and possibly sausages or pieces of braised pork were arranged in concentric circles. The bits of meat were a real treat for children in the poor, farming communities. Young and old alike were given forks and everyone would make their own trails in the hot mess of deliciousness, each staking out their own section. But as I've been told, in some homes there were rules: you weren't allowed to eat the meat until you ate a path to the center, with some slow eating children not having such luck! This manner of eating is a celebration of nature from the 15th century when corn was introduced to Italy from the New World. This dish is a celebration of the recent harvest... the circular shape of the polenta represented the sun, and it's corn having come from Mother Earth herself. All the ingredients topping this sun would have also been nurtured by the sun during the growing season: lentils, chickpeas, pork, chicken. This is an ancient meal that also celebrates life--and family. So everyone was at the table digging in. This is a big meal... with a large amount of polenta traditionally prepared in a copper pot resembling a modern wok. Nowadays, people tend to use a Spianatora (or spianatoia)--a modern day wooden cutting or pastry board--to pour the polenta onto. There are even some restaurants in southern/central Italy that will service this during the holiday season. To make this warming meal for your famiglia, first you need to make a Sugo. Here's a link to my own family's Sugo Recipe.  on Amazon on Amazon For the Polenta

Top this beautiful, hot mess with Parmigiano Reggiano or Romano and invite your amici and famiglia to start scraping. Buon appetito, Buon Natale and Felice Anno Nuovo! --Jerry Finzi In Italy, there is a saying, "buono come il pane"... or, "It's as good as bread". This saying is used to compliment the best cooking. Think about it... that's how high Italians value a food as simple as bread, to compare other meals to it. You can't get simpler or better than the humble panino... During our Voyage throughout Italy, one of the simplest and affordable lunches was the panino. Most types of eating establishments have them: the trattoria, pizzeria, ristorante, osteria, taverna, tavola calda (a sort of Italian fast food shop) or bar (all bars are open for breakfast or lunch). In a tavola calda (literally, cold table) might include a wide range of lunch options, both sandwich style and stuffed. A new type is called a paninoteca, which is a shop dedicated to panini and typically open only in the middle of the day for lunch. They are designed as a grab-and-go place, but many will have a few tables. In tourist areas, the restaurants tend to overcharge, but a panino was always an affordable and very satisfying option. In mornings, we also would stop in the local alimentari (like a corner deli) and pick up some cold cuts, cheese and bread to make our own panini while on the road.  One of our favorite (and most used) kitchen appliances is our panino press, the Cuisinart GR-4N 5-in-1 Griddler. We've had ours for about 5 years and it's still in perfect condition (the plates are non-stick and clean well). You can't beat their low price, either. We use the flat platens for making pancakes and switch to the ridged grill plates to make panini. We buy ciabatta with olive oil from the supermarket and can make a couple of fantastic panini in about 5 minutes. One of our favorite ways to make a panino is to slice up some supermarket mozarella-salame rolls (some brands market these cheese rolls as "panino") along with slices of heirloom tomatoes on ciabatta. Set the panino press on high, give it a press for a few minutes and we're back in Tuscany! A Short Panino History The word "panino" literally means "little breads". In Latin, panis means bread. A panino doesn't really need to be heated, as in Italy it is often eaten as a quick snack on the run, in the field, or in the case of an Italian bachelor.... "Ehi! Mamma, make me a snack!" Stuff some peppers and ham inside a small bread roll and Mama gives her big "bambino" a satisfying, quick snack without much effort. (She thinks, "After he gets married, HE is going to look after ME.") This type more precisely is called a panino imbottito, literally "stuffed little bread". Basically it's the same as any American "hero", "hoagie" or deli sandwich. Similar to a panino is the tramezzino, a grilled/pressed sandwich made with slices of hearty white bread, sliced diagonally with the edge crusts removed. If you want a sandwich in an Italian bar, they will ask if you want it "da riscaldere" or "riscaldo" (reheated), "alla piastra" (literally, on the plates), then they will usually place the panino onto a press in between two flat platens, although many will use ridged ones. Throughout early history, bread was considered an entire meal, until it became the support (think foccacia or pizza) or container for a condiment or filling--the sandwich. Historians have found recipes for grilled sandwiches in cookbooks from the ancient Romans and it is belived that sandwiches were common across many ancient cultures. (Take that, Earl of Sandwich!) The bread in the photo above recreates a Roman bread, baked pre-cut into wedges (to pull-apart) and with a string tied around its waist to create a division to help pull the bread apart into two halves. The reason? To put fillings between the slices, what else? In hotos of carbonized breads found in the ruins of Pompeii, while the top was pre-sliced, the bottom half was not. Perhaps they could alternately use the bottom as a support (an edible plate) for fillings? The first reference of a panino appeared in a 16th-century Italian cookbook, with the first mention of "panini" appearing in 1954 in the New York Times in an article about an Italian festival in Harlem: "The visitors ate Italian sausage, also pizze fritta, zeppole, calzone, torrone, panini, pepperoni, and taralli." Panini as we know them today, became trendy in Milanese bars, called paninoteche, in the 1970s and 1980s. In fact, in Italy during the Eighties, a cultural fad developed in Milano where teens would meet in panino bars,... the teens were called paninnare. In Sicily, Panini cresciuti ("grown rolls") are fried Sicilian potato rolls containing ham and cheese. Today in Italy, shops that specialize in panini are called panineria, although many of these have morphed into offering a smörgåsbord of many types of sandwiches, not just the classic panino. In Italy, sandwich shops traditionally wrap the bottom of a panino in a sheet of white paper, a way to keep hands clean, making this a true finger food. It couldn't be simpler...  This time I made our panini with slices of salami-mozzarella roll (Boar's Head brand "Panino" roll is nice and spicy, and they also have a Prosciutto version). I find so-called "panino rolls" are becoming a commonplace item in the supermarket fresh cheese section. I learned in Italy that some of the best things can be very simple. This lunch is a good example of this philosophy. Quick, healthy, simple. You can also get more creative too... using grated cheeses like fontina, asiago, smoked gouda or cacciacavalo and using leftover chicken, prosciutto, sausage, caramelized onions, olives, peppers... whatever. (I love making a panino using leftover chicken parmesan!) I highly recommend using a bit of smoked cheese which adds tons of flavor. Today's panino, however, was an ad hoc, simple lunch, like the ones I threw together in Italy. I cut the ciabatta in 4 inch long sections the sliced each horizontally and unfolded them to open. I then slice the salami-mozzeralla into slices a bit less than 1/4" thick and lay 4 on each ciabatta. Some say you need to butter the outside of your bread or brush it with olive oil to make grill marks or a crust, but I omit this step, preferring less fat intake. Besides, I tend to buy "olive oil ciabatta", which helps the browning. if you want more browning, feel free to lightly brush some olive oil on the outside of the panino before cooking. Butter is rarely used in Italian cooking and is never spread on bread, so I wouldn't use it. You can drizzle the contents of your panino with a little olive oil or perhaps a good balsamic, or even a decent store bought Italian dressing. I like to add slices of the best tomatoes I have around, adding moisture to my panino. Black olives or other giardinaria (pickled veggies) are also a good choice. My son, Lucas loves sweet pimentos on his. Try spreading some pesto on the bread too! Setting my panini press to "grill" and to high heat, I let it preheat for a couple of minutes and then load the panini (I can only do 2 at a time of this size). I give it a good pressing at the beginning and try to position the bread (front to back... there's a sweet spot) so the press lid sits flat. After about 2-3 minutes, I give a final press--hearing the panini sizzle. I hold this press for about 30-40 seconds, pull them out, plate them and slice diagonally into triangles. With panini, the longer you press it and hear the ingredients sizzle, the more crunch you will have in your bread. Too many people think a panini is buttered and grilled bread with cold cuts put inside unheated, and many restaurants order packaged sandwich bread with grill marks factory-burned into their crusts, then use it to make make a normal sandwich, calling it a panini. I've even seen sliced factory "panini bread" with the "grill" marks already there. Shame! A true grilled panino must be pressed and heated to meld the ingredients (that's meld, not melt) into one cohesive, gooey mess of deliciousness. And take note, if you use cold cuts and sliced cheese, the cheese must be placed both on top and on the bottom--the melted cheese helps hold the bread together. A grilled panini is not like a normal sandwich... you should not be able to lift the bread off after it's been pressed and cooked. That is, unless you're in Italy, where most basic sandwiches are known as "panini". What I make is a grilled panino. So, get yourself a panino press (no need for an expensive one) and start cooking. Buon appitito! --Jerry Finzi |

Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

|