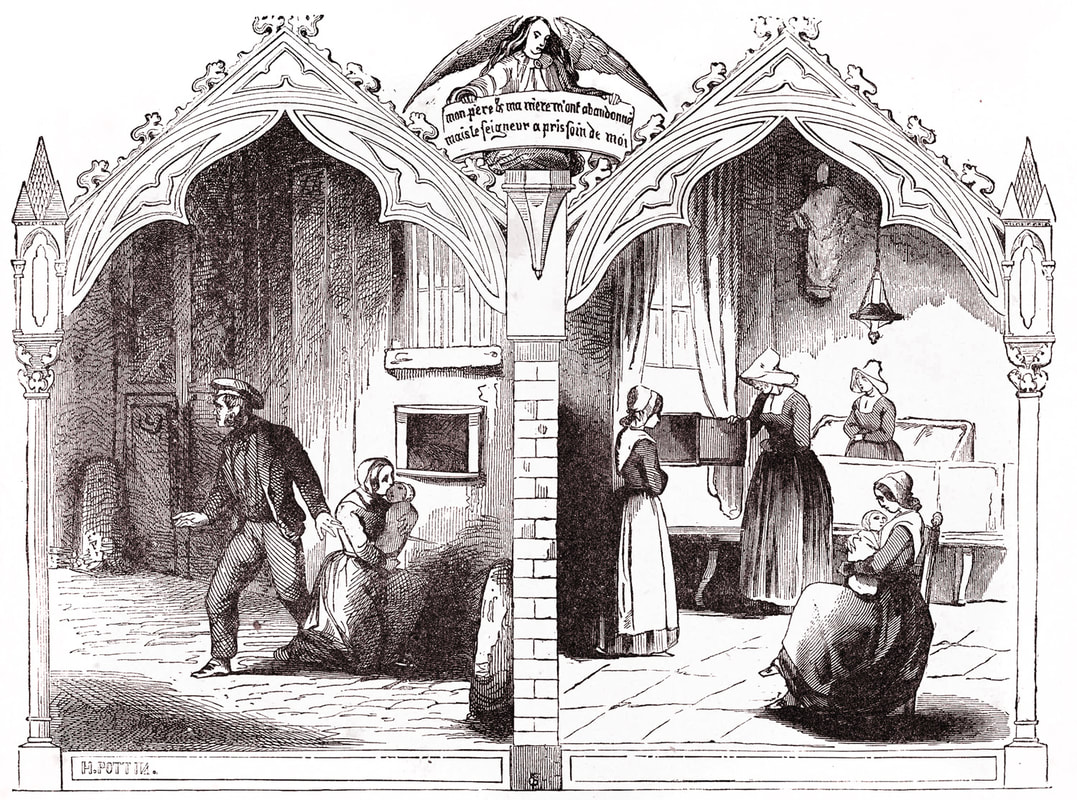

Ospedale Santo Spirito in Rome Ospedale Santo Spirito in Rome I’ve researched and written on orphans and adoption customs in Italy before, but in the last few months I’ve come up with another reason to be interested in Italian orphanages… I’ve discovered that my great-great grandfather was an orphan. Apparently, the “First Anselmo” as we are calling him (there were more after him) was offspring of a nobleman from Molfetta and a servant girl. We have the surname of the father but only the first name of the mother. After being educated in the orphanage at Giovinazzo, Puglia he lived with two other families, neither of which had the surname Finzi. So we have a new family mystery to solve… why Finzi? And why Catholic? (Most Finzis in Italy are Jewish). I suppose that someday I might get my hands on the adoption records from 1836. I’ve read that there can be a lot of information gained due to the narrative style of report written about each foundling during that period. But in the last part of the 19th century, the adoption procedures slimmed down to the barest of information. However, if the foundling was placed in a Ruota del Trovatello (Foundling Wheel), there might never be any information about who the parents of the child were. You see, the Ruota was a type of drum shaped cabinet on a pivot, used in orphanages to receive unwanted babies--anonymously.  During those hard times, there were a significant percentage of abandoned babies from both unmarried women and married couples. Poor peasants with several other children could not afford to feed yet another child. They would anonymously abandon the child at the Ruota, typically built into the wall of the local convent or Ospizio (orphanage). The problem of unwanted newborns has been documented in Italy since Roman times when babies abandoned next to a column in a forum were either taken home by strangers to serve as slaves or left to die. Pope Innocent III was so shocked by the large number of dead babies floating in the Tiber River that he institutionalized the “foundling wheel” in the 12th century as a solution for dealing with the large number of foundlings—infants abandoned by their parents and left to die or be discovered and cared for by others. The size of the Ruota was purposely kept infant-sized to prevent older children from being abandoned. Older children were thought of as workers and laborers, and rather than be abandoned, worked on the farm or became apprentices to a local tradesman.  The practice of using foundling wheels to dispose of unwanted children gained in popularity and became a common practice in medieval Europe. By the early part of the 19th century, names were often recorded when people gave up their children to the orphanage or church openly, a practice often done when there might come a time when they wanted the child back—as they became more solvent or when an older child could work on a family farm. But surnames could never be known when they put the child in the Ruote. For this reason, many often pinned a charm or special memento to the child that could be identified if they ever wanted to reverse their decision. The babies were given surnames such as Esposito (exposed), Proietti (thrown away), and Innocenti (innocent). People with such names can usually trace their family tree back to a foundling. It was only after 1926 that an Italian law banned the use of such discriminatory names, when names were given to describe the time of year (Primavera) or the month (Maggio) the child was abandoned. (Read more about orphan names HERE) Safe Ways to Abandon Babies in Modern Society In many countries, there are still modern versions of the Ruota… usually a climate controlled drawer in which a baby could be placed. Multilingual posters in modern Rome read—“Don’t abandon your baby! Leave it with us.” The practice of placing unwanted infants in a modern foundling wheel, heated baby hatch, stork cradle, stainless steel baby box, maternity ward, or designated safe haven is a practice that is still used today in many European countries and the United States and the practice is gaining in popularity throughout the world to combat child infanticide. Some legal problems with modern baby hatches are connected to a child’s right to know their own identity, as guaranteed by the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. Baby hatches also deprive the father of his right to find out what has happened to his child, though DNA testing of foundlings would seem to offer a partial solution. I suppose as strange as the Ruota sounds, it has saved the lived of countless children in Italy and around the world… As for me, I now know we come from a lineage of Finzi’s that come to a sudden, mysterious beginning in 1836. Since my great-great grandfather seems to have been placed into the orphanage with some paperwork filled out, perhaps someday I’ll be able to continue to trace our family tree further and further back in time. --Jerry Finzi |

On Amazon:

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed