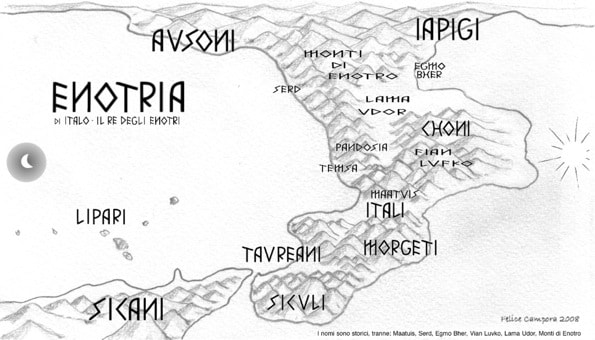

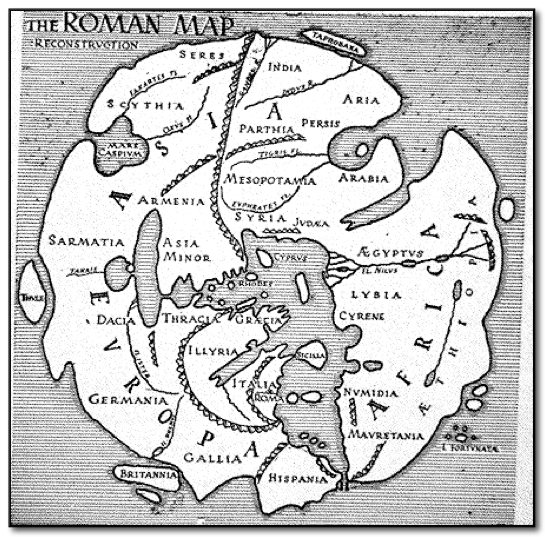

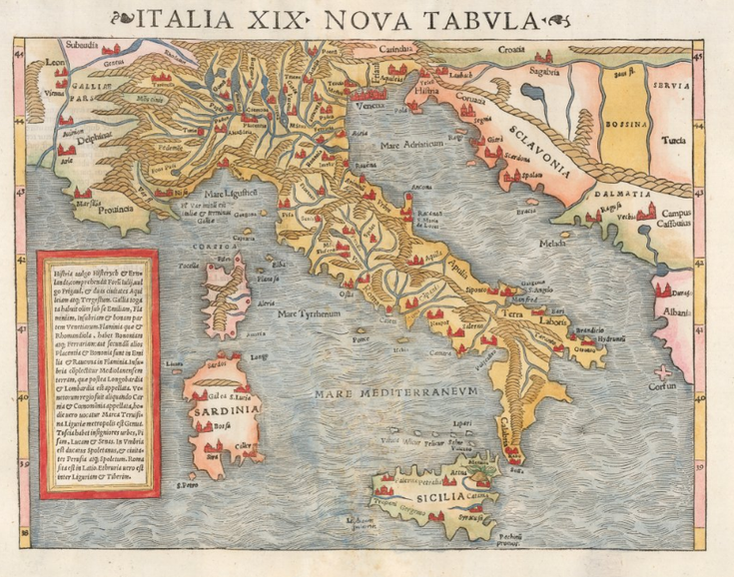

The name Italy (in Italian, Italia) evolved from variants of different names used in the ancient world as early as 600 BC in what we know today as the Italian peninsula. Historians are still researching its origins, but "Italia" surely evolves from Oscan word Víteliú (spoken by the Samnites), meaning "land of young cattle". A modern variant is vitello, the Italian word for calf or veal. In Roman times, vitulus was the word for calf. The ancient Umbrian word for calf was vitlu. Coins bearing the name Víteliú (𐌅𐌝𐌕𐌄𐌋𐌉𐌞) were minted by an alliance of several Italic tribes: the Sabines, Samnites, Umbrians and others who competing with Rome in the 1st century BC. Another theory is that the name stems from the Greek Italos, a legendary king of the Oenotrians, people of Greek origin who inhabited a territory from Paestum in the Campania to southern Calabria, among the earliest inhabitants of Italy. Italus was supposedly the son of Penelope and Telegonus, a son of Odysseus. It was both Aristotle and Thucydides who first told of Italus being who Italy was named after. The Greeks gradually came to apply the name Italia to a larger region covering most of Southern Italy, but it was during the 1st century BC that Augustus expanded the name to cover the entire peninsula including the Alps. The Greeks referred to these people as Italoi. Under Emperor Diocletian the Roman region called Italia was further expanded to include the islands of Sicily (including the Maltese archipelago), Sardinia and Corsica. Another reason for the name might come from the Greek word Aethalia, meaning "land of fog and smoke", referring to its many volcanoes. Mount Etna gets its name from the same etymological root. The Holy Roman Empire adopted the name Italia to describe its own territories in the central peninsula, and afterwards, the name was used to describe virtually the entire peninsula. In Middle English, the lands were called Italie. Later, in the 14th century, Dante described "Italia" as a land including lands from the Alps to the tip of the Italian boot, and including the islands of Sicily. The last theory intrigues me the most...

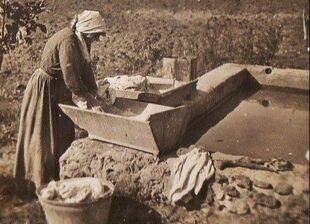

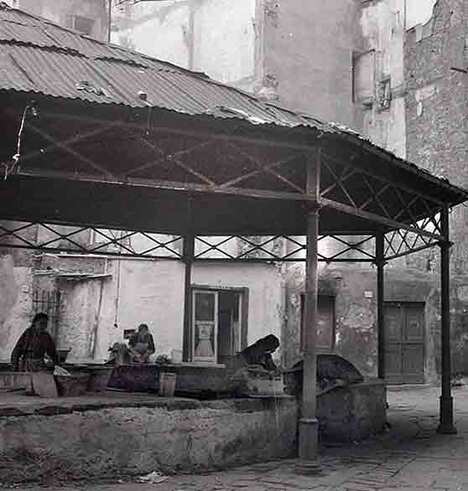

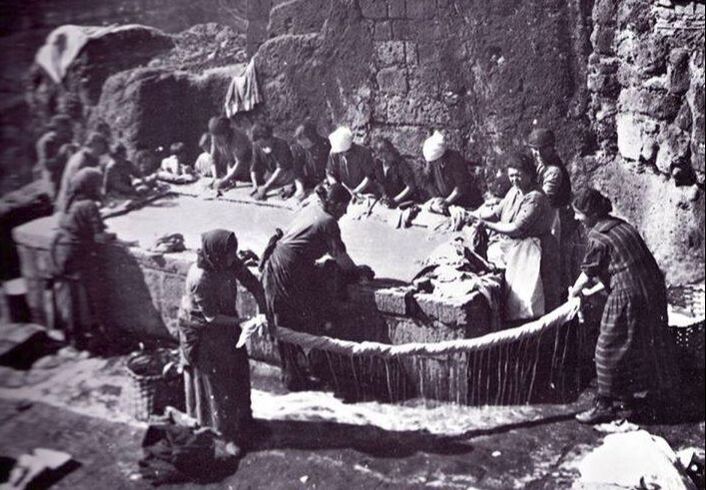

Eurystheus ordered Hercules to travel to the End of the World and bring him the cattle of the monster Geryon. Hercules succeeded in stealing the cattle but had enormous difficulty bringing the herd back to Greece. In Liguria, two sons of Poseidon, the god of the sea, tried to steal the cattle, so he killed them. At Rhegium, a bull got loose and jumped into the sea, swimming all the way to Sicily and then made its way to the neighboring country. The native word for bull was "italus," and thereafter this country came to be named after the bull. Perhaps this, stubborn, strong-minded bull is a perfect image for the naming of this amazingly resilient and tough country. Italia, Aethalia, Italie, Víteliú... and of course, the current day Italy is a never-ending source of history and amazing stories. --Jerry Finzi  My first memories of my mother doing the wash was of the squishing, splashing and grinding of our old white enameled motorized washing tub in our cellar. It had rollers stuck on top to squeegee most of the water out of the clothes, getting them ready to hang out to dry on our clothes-line overhanging our back yard garden. I often had the job to "take in the clothes" from the line. In summer I loved doing this, hanging out the window and pulling the line closer on the pulleys as I worked, and afterwards nuzzling my nose into the sun-warmed towels and shirts, sucking in the freshest smell imaginable. In winter, I would pull in cardboard-like, frozen clothing... pants and shirts looking as if someone was flattened by a steam roller. The towels would be stiff as a large baccala dried fish. As modern conveniences developed, my mother got a washer and dryer in the basement of her new suburban house. Even when she was well into her eighties, I remember visiting and catching her, moving one step at a time, bringing up a basket of laundry from the cellar, all folded neatly and smelling almost a nice as when we sun-dried them. She was a tough lady. Her mother was even tougher. In her Hoboken, NJ apartment, she washed her clothes in a sink using only a washboard. As I write this, I'm listening to be beep-beeps and musical chimes produced by our front load modern washer in our second floor laundry room. It's nearly effortless, allowing my wife Lisa to drop a load of wash as she heads up to her third floor office. OK, I know... I should do the laundry more often. Nowadays, doing the laundry is not just women's work.  Hauling water Hauling water Le Lavandaie of Italy's Past When we complain about how hard it is to do household tasks, I often think of how our Italian ancestors dealt with the hardships of everyday life. Looking at historic photos of the lavandaie (washerwomen) of Italy's past, I consider how hard Italian women had to work at cleaning their cloths. Early on in history, the contadina (country woman) would wash clothes in the nearby river, on her knees, regardless of season or weather. They would bring a wooden washboard to the river, some of these were very wide, offering a communal laundering experience. Some households had their own wooden troughs with a washboard built-in, but water would still have to hauled from the river or local fountain in order to use it.  It wasn't until 1897 that the first public lavatoio (wash house) was built in towns and villages around Italy. Some had roofs with open sides--similar to market structures--to keep the women out of the sun and rain. Many were built near existing streams, and were designed to direct the fresh running water through a trough. Still others had plumbing and elevated wash tanks, allowing women to stand while they washed clothes. What a luxury this simple change must have been! At the bare basics, a lavandaie needed troughs or tubs where fresh water ran through, and an inclined concrete or stone ramp where they could soap up and agitate the clothes and sheets with a two-handed motion similar to kneading dough. Then they would slap the clothes on the ramp to rid them of suds, dirt and odors. They used solid soap, often made locally as a by product of the slaughtering process. White fabrics, especially sheets, needed to be bleached--a bit of a complex process. The day before, sheets were soaked in boiling water with wood ashes (the bleaching agent, called ranno) and bay leaves, lavender or rosemary (adding a fresh scent). To dry, first the sheets were beaten and then it took two women to wring them out due to the heavy, waterlogged weight. Both clothing and sheets were hung to dry in the sun. Still today in modern Italy, hanging clothes in the sun is the preferred way to dry clothes and while Italian households today might have a washer, they rarely have a clothes dryer. Some women called bugadere did the laundry for people who could afford to pay for the service. This was a profession for women only, and only for single women, since most men wouldn't want their wives touching other peoples' dirty laundry. As you can surmise, this was considered a lowly profession. Housewives who did their family's laundry would go home when finished, but the bugadere was at the lavatoio all day long. Some of these "professional" washerwomen stayed at the village lavatoio and women would bring their laundry to them for washing. Others had clients and went to homes to pick up the laundry, carrying the heavy loads in jute bags (often on their heads). Each client's laundry was identified with a different color ribbon tied to each bag because writing a name on each would have served no purpose since most were illiterate. You can often find a woman''s profession listed as "washerwoman" on some Ellis Island ship manifests. If you find a washerwomen in your history, be proud. That must have been a tough way to earn a little money to contribute to the welfare of their families. Washing Methods and Materials There were various detergents used by lavandaie. The most common and also the least expensive was the so-called ranno, used both for for degreasing and bleaching. The technique involved filtering hot water poured over wood ash through an old linen sheet draped as a filter over a large bucket. Underneath this ash filter were the previously washed fabrics to be bleached. Many lavatoio also contained a large hearth with a large suspended cauldron to heat water for the ranno bleaching. In later years, de-greasing was accomplished by the use of sodium carbonate (similar to baking soda); lye solutions, used both for washing and whitening; Varecchina, for bleaching and stain removal; during the first rinse or ranno, crushed eggshells were added; indigo was also added as a blueing agent; in the final rinsing, lavender, bay leaves or rosemary were added to provide sweet or fresh scents; as bar soap became available it was also used, often grated into smaller pieces that could be sprinkled on clothes as they were washed. --Jerry Finzi Copyright 2020, Jerry Finzi/GrandVoyageItaly.com - All Rights Reserved In the video above, these ladies are seen adding wood ash to their tub to start the bleaching of their sheets. School boys hosting a historic demonstration by these lavandaie. A traditional song about washerwomen.

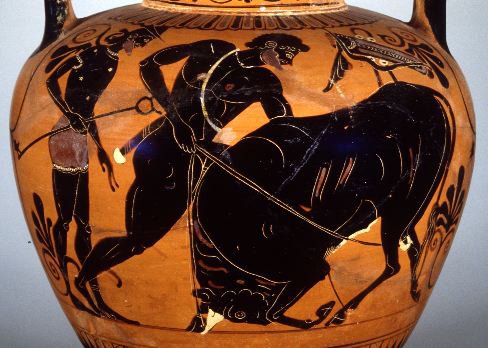

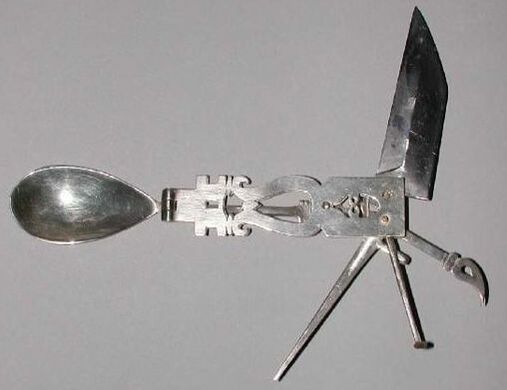

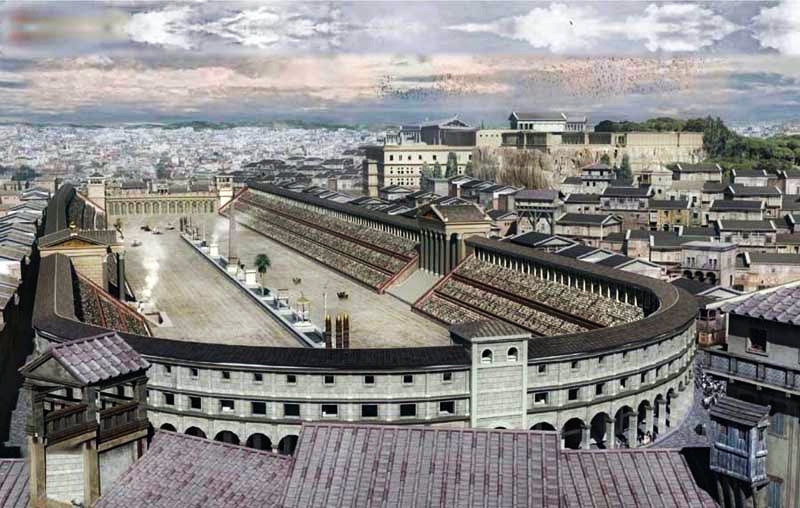

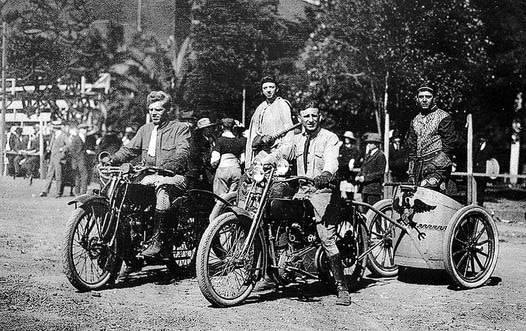

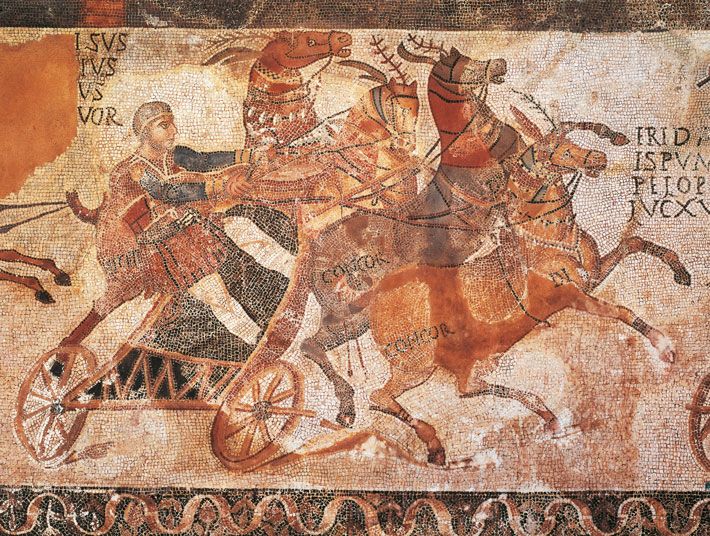

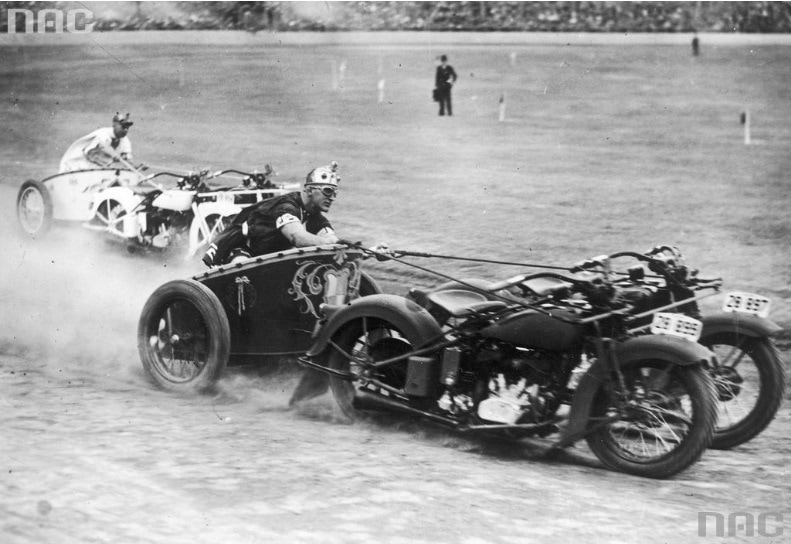

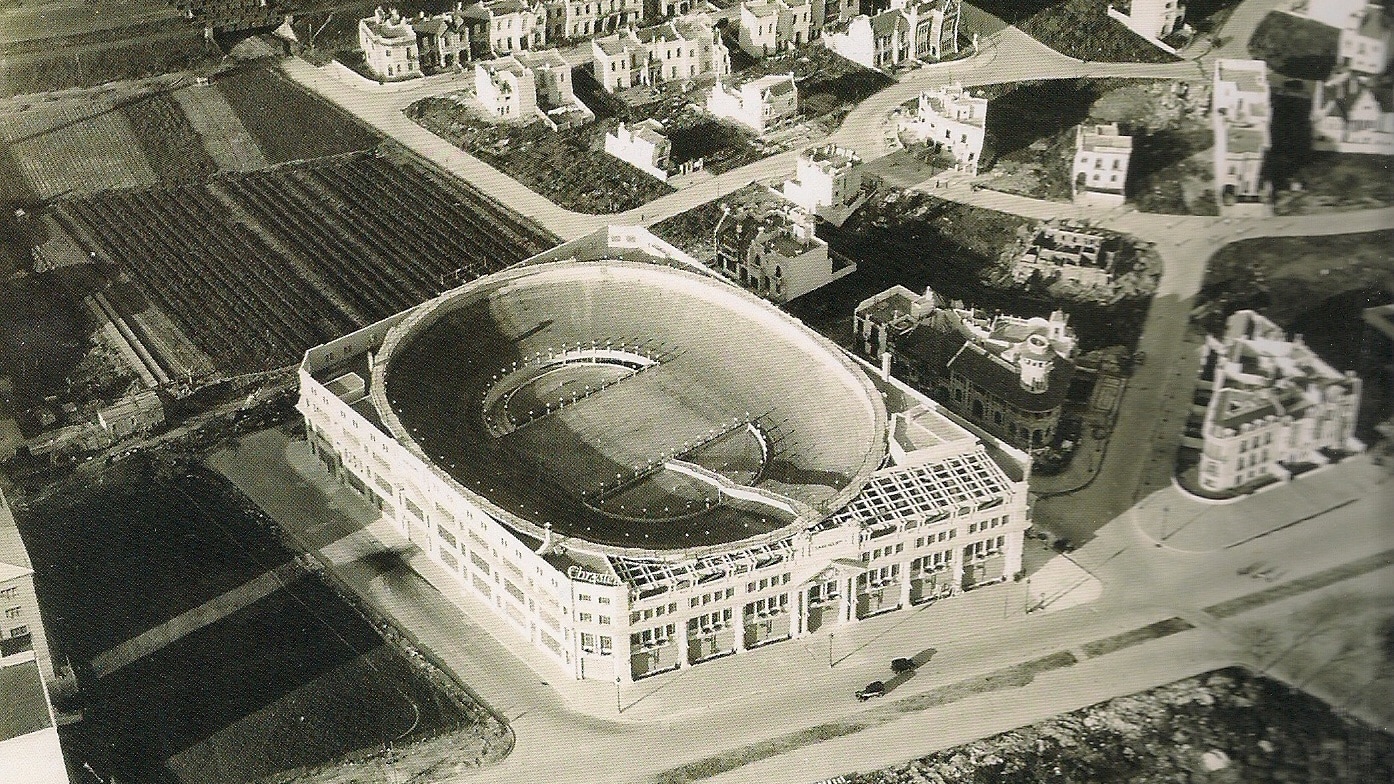

A modern public pay phone uses credit cards A modern public pay phone uses credit cards Back when I lived in France, before the advent of cell phones, this was the way you made a phone call in France, and in most of Europe... the pay phone. They were usually located in bars in both France and Italy. Remember, a bar in Italy is a not like a bar here in the States. It's a place to get your morning coffee and sweet pastry before heading off to work... a place to get the news and gossip from your neighbors... a place to get a sandwich or some sort of stuffed pizza for lunch. In the past, it was also where you bought gettoni--a special coin used only in pay phones. Shove the gettoni in the phone, hear the dial tone and dial your number... or was it the other way around? It was always a bit confusing for visitors. I do remember they worked a bit differently than American pay phones. You may still encounter pay phones in Italy, but nowadays they take credit cards. Be wary of instructions on the phone to make international calls! Even though they look official (perhaps being under plexiglass), they are scams! Smart phones are a Godsend when traveling through Italy nowadays... --Jerry Finzi We all know the Swiss Army knife with knife blades, toothpick, comb, scissors and more folding out from its case. The Swiss are fairly innovative, but this is one invention that the ancient Romans might have beat them on. This example of a Roman multi-tool was used nearly 2000 years ago and discovered in an unspecified Mediterranean site. This intricate design dates from around 200 AD and is made of silver, with an obviously rusted iron knife blade. It has implements that fold out for use: knife, spoon, fork, spike, spatula and small tooth-pick. Some believe this was an eating and grooming instrument carried by Roman troops, but more than likely, because it was made of silver, it was used by a higher ranked official of the Legionnaires or possibly a political figure--definitely a wealthy Roman traveler. It is in the Greek and Roman antiquities gallery at the Fitzwilliam Museum, in Cambridge, England. --GVI Were the ancient Romans ahead of their time? The famous Lycurgus Cup in the British Museum might be proof that they were indeed very advanced in the sciences, especially in the field of Nanotechnology. The 1,600-year-old glass goblet does something very magical: It changes color from jade-green to blood-red depending on the direction of its illumination... with the light source from the front, the goblet appears green, from the rear it changes dramatically to red. This is called Dichroic behavior. The Roman craftsmen who created this work of art either knew about the science behind it, or stumbled unknowingly onto its special characteristics. As they might have put it, felix accidente, a happy accident. The Romans may have been the first to discover the colorful potential of nano-particles by accident, but they seem to have created the world's most perfect example of the phenomenon. The Artistry of the Chalice The Lycurgus Cup is also a very rare example of a Roman caged cup, or diatretum. The glass has been painstakingly cut and ground back to leave only a decorative "cage" on the surface with extreme undercutting. Instead of the more common abstract, geometric design, the Lysurgus Cup contains beautifully detailed human figures. It shows the mythical King Lycurgus, who attempted to kill Ambrosia, a follower of the god Dionysus (Bacchus). She was transformed into a vine that twined around the enraged king, killing him. Dionysus and two followers are shown taunting the king. Such figures on a caged cup are otherwise unknown. History of the Cup The Cup is thought to have been made in either Alexandria or Rome around 290-325 AD, measuring 6 1/2" x 5". Judging from its excellent condition, it more than likely was never buried and was always kept as a treasure, at first in a noble Roman's villa, then in a church and later in the collections of the elite. There is also the possibility that it was recovered from a sarcophagus. The gilt and bronze feet were added late in its life--about 1800, making some think it was looted from the church during the French Revolution. It's more than likely that earlier mounts existed, but wore away with time and use. No one really knows the earlier history of the Cup. One can ponder about who it was originally created for, perhaps an emperor? The Science Behind the Chalice: Dichroism The Lycurgus Cup was mentioned in French writings as early as the 1845, but no one knew why it changed color. The British Museum acquired the Cup in the 1950s, but it wasn't until 1990 that researchers examined small broken shards under an electron microscope and discovered the secret. Whether or not the Romans stumbled into it, the artisans were truly nanotechnology pioneers. Nano-particles of gold in the glass on a microscopic level is the reason for the color change. (Gold added to glass makes red glass, as in stained glass windows). It's unknown whether the Roman artisans impregnated the glass with particles of silver and gold on purpose, or whether the glass was somehow already "contaminated" before they used it. Researchers found particles as small as 50 nanometers in diameter, less than one-thousandth the size of a grain of salt. Some think that exact ratio of the mixture of the precious metals suggests the Romans certainly did know what they were doing. This is how the technology works: When hit with light, electrons belonging to the metal flecks reflect frequencies into our eyes in ways that alter the color depending on the observer’s position in relation to the light. Was the Lycurgus Cup a Poison Detector? During the Renaissance, the ruling class believed that goblets and glassware made on the island of Murano in the Venice lagoon would vibrate and shatter when poison was poured into them. Although false--and likely just marketing hype aimed at the ultra-rich so they would pay more for glassware--perhaps this long held notion was based in some long-distant reality... a capability of cups like the Lycurgus, perhaps? Gang Logan Liu, is an engineer at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and has been focusing on using nanotechnology to diagnosis and treat disease. He explains, “The Romans knew how to make and use nano-particles for beautiful art. We wanted to see if this could have scientific applications.” Liu theorized that when a nano-treated vessel was filled with various liquids, the vibrating electrons would change the color of the glass according to the type of liquid used. The use the Lycurgus Cup to test his theory could never be allowed for fear of damaging a priceless Roman artifact. So he created this experiment: The scientists imprinted billions of tiny wells onto a plastic plate about the size of a postage stamp and sprayed the wells with gold or silver nano-particles, essentially creating an array with billions of ultra-miniature Lycurgus Cups. When water, oil, or sugar and salt solutions were poured into the wells, they displayed a range of easy-to-distinguish colors—light green for water and red for oil, for example. The prototype was 100 times more sensitive to altered levels of salt in solution than current commercial sensors using similar techniques. Were There Other Dichrioc Cups the Ancient World? Yes, it seems that the ruling class were well aware of them, owned them, gave them as gifts and drank from them on special occasions. However, only a handful of Roman dichroic glass objects are known to exist. Only 50 or so late Roman cage cups themselves exist, but even rarer, fewer than 10 dichroic glass objects have ever been found, and all of them (aside from the Lycurgus Cup) are mere fragments. Objects of such rarity with the extraordinary property of changing color would obviously be bought or commissioned by only privileged Romans. There are some ancient texts that discuss them... From Vopiscus' life of the third-century pretender Saturninus is a letter claimed to be written by emperor Hadrian (117–138) when he was in Egypt. Written in the early 4th century AD, Hadrian describes a gift to his brother-in-law Severianus in Rome: "I have sent you parti-colored cups that change color; presented to me by the priest of a temple. They are specially dedicated to you and to my sister. I would like you to use them at banquets on feast days" From the novel Leukippe and Cleitophon by Achilles Tatius (a second-century AD Alexandrian): The hero, Cleitophon, is at Tyre, where he attends a banquet given by his father on the feast day of Dionysus. During the meal, the host offers libations from an unusual vessel: "My father, wishing to celebrate it with splendor, had ... a precious bowl to be used for libations to the god ... Made of crystal... Vines crowned its rim growing from the cup itself, their bunches drooped in every direction. When the cup was empty, each grape seemed green and unripe, but when wine was poured into it, then little by little the clusters became red and dark, the green crop turning into the ripe fruit. Dionysus... was represented, near the bunches, as the husbandman of the vine and the vintner." Both of these texts describe very similar drinking vessels as the Lycurgus Cup. In the second text, you can imagine the cup from the drinker's perspective--filled with dark red wine, the outside of the cup was green. Then as the drinker lifts his glass and peers into it, the light passes through the side and it looks as if the grapes have turned red! The Lycurgus Cup was obviously a cup from Roman royalty that was treasured and cared for throughout the last 1600 years until modern scientists unlocked its secret. The Romans perhaps knew how to make and use nano-particles to create a beautiful object, but modern scientists think that nanotechnology can be useful in a wide range of scientific fields: chemistry, biology, physics, materials science, and engineering. Of course, perhaps equally amazing is the sheer beauty and artistry of the Lycurgus Cup. The capabilities of ancient Romans never cease to amaze me. --Jerry Finzi Watch the video below to see the changing colors... Museo Galileo - Museum of the History of Science in Florence  Galileo invented many mechanical devices besides the telescope, such as the hydrostatic balance, a pendulum clock and a high power water pump powered by one horse. Of course, his most famous invention was the telescope. Galileo made his first telescope in 1609, modeled after telescopes produced in other parts of Europe that could magnify objects three times. He created a telescope later that same year that could magnify objects twenty times. You might argue that although he didn't invent the first telescope, he obviously improved upon it. With this telescope, he was able to look at the moon, discover the four satellites of Jupiter, observe a supernova, verify the phases of Venus, and discover sunspots. His discoveries proved the Copernican system which states that the earth and other planets revolve around the sun. Prior to the Copernican system, it was held that the universe was geocentric, meaning the sun revolved around the earth  "Engines" were small at first - a Half-Horsepower (Donkey) powered cart "Engines" were small at first - a Half-Horsepower (Donkey) powered cart No one really knows when chariot racing started, but the Greeks had chariot races during the first millennium BC and made the races part of the Ancient Olympics in 680 BC. Of course, chariots themselves were in use 4000 years ago. The most important development was a wheel with spokes. Before spokes, wheels were made from solid slabs of wood or thick shaped planks--both added weight before the cargo was even placed into the cart. Carts being pulled by animals--mostly oxen--were in use as early as 6000 years ago... but having an oxen as your main engine was very low torque--like a Mac truck. "Engines" improved slowly... at first a donkey or even a goat... sort of like early Model-T Ford runabouts. Then higher horsepower came in the form of mules and horses, one horsepower to start. The first chariots were used as delivery and work vehicles.  This car just wasn't fast enough to avoid the Law This car just wasn't fast enough to avoid the Law The history of NASCAR racing started with delivery vehicles, too. During the period of Prohibition in the 1920s, a bunch of backwoods good ol' boys smuggled liquor in from Canada or bootlegged whiskey (moonshine) from the tobacco fields of Georgia through to Chicago, New York and other big cities. Especially in the deep South, illegal booze was transported with with stock cars... they needed to look like every other car so as not to attract much attention. But special equipment was needed for the task at hand: heavy shocks and springs were added for the weighty loads of filled bottles and jars, and for smoothing the ride when driving fast on bumpy, unpaved roads; a high-powered engine was needed to deliver their booty quickly and to leave chasing authorities in the dust. High performance stock cars were born when Federal agents took chase... You can imagine that chariots started out also as "stock" units, with additions and modifications needed to accomplish their task. Adding a horse in place of a goat (more horsepower--literally) meant goods could make it to market faster and beat the competition. Perhaps this is where chariot racing started... two lemon growers meeting on the road and trying to beat each other to market. I'm certain that Greek and Roman officials taxed wine heavily, giving the ancient wine producer reason to race their "special" supply of wines past tax collectors to their regular clientele. Up until the 1st century AD, chariots were also used in the military. Racing to overcome the enemy, or perhaps betting on who would get to the battlefield first, might have also planted the seed of chariot racing. Special performance equipment on chariots continued to advance. In Ancient Rome, a two horse chariot was called a biga, a three horse chariot was a triga, and a supercharged, four horse power chariot was called a quadriga. Hey, they all sound like great names for modern car models! Vroom, Vroom! The horse chariot was a fast and lightweight vehicle and was indeed Spartan inside... again, like a NASCAR vehicle. There was barely a floorboard, no windows, and a waist-high guard at the front and sides. It must have been as uncomfortable a ride as what NASCAR race drivers have to put up with. Unlike other Olympic events, charioteers in Greek races did not perform their sport in the nude. Like NASCAR drivers, they wore safety gear: The clothing was itself their safety gear... a sleeved garment called a xystis went down to the ankles and had a belt fastened at the waist. Two criss-crossed straps across the back prevented the xystis from filling up with air during the race. Roman charioteers wore more protective gear--perhaps because most were not slaves, but paid professionals. They word helmets, leg guards, body armor or chain mail and wrapped the reins around their forearms. In case of a crash they would be dragged along the ground and could be killed, so one final bit of protection was to carry a falx (a curved knife), used to cut their reins away in an emergency. When official chariot racing became popular, it wasn't the driver who owned the horses and chariot. Just as in NASCAR, there were team owners. In 416 BC, the Athenian general Alcibiades had seven chariots in the race, and came in first, second, and fourth. He obviously hired drivers to be at the wheel... er... at the reigns, that is. Unlike NASCAR drivers who some might argue are slaves to their sponsors, many drivers (who remain unknown to this day) were actual slaves. The racetrack--called a Hippodrome (Greek) or a Circus (Roman)--was oval with tight turns on either end, just like (getting tired of saying this) NASCAR courses. Chariots went around and around, counterclockwise, with nothing but left turns (sound familiar?) These turns were deadly and many crashes occurred. Although running into an opponent with the intent to cause a crash was strictly forbidden--it was tolerated because it made the crowds go wild. The ancient Greek and Roman spectators loved crashes, as they loved any blood sports of the day. Modern NASCAR spectators are conflicted--as loyal fans, they don't want to see their favorite drivers injured or killed, but just as the ancient spectators, when a crash happens, they get an adrenaline rush and a thrill they'll remember for a lifetime. Chariot races began with a procession into the hippodrome, while a herald announced the names of the drivers and owners--he had to be a very loud public speaker, indeed. NASCAR tracks have lots of loudspeakers. On the flip side, aside from cheering crowds and the sound of horses hooves on a dirt track and the occasional cracking of wood during a crash, a chariot race must have been a quiet affair when compared to the off-the-scale high decibel assault the NASCAR fan must endure as car after car go revving by for hours on end at up to 200 miles per hour! The smells were very different too... horse poop versus the exhaust from 110 octane fuel and burning rubber...  Ready to throw down the "Mappa" for the race to start Ready to throw down the "Mappa" for the race to start A race called the tethrippon (in Greek regions) had twelve laps around the track, while Roman races often had 7 laps to allow more races in a single day for betting--Romans and gambling went together more than in the Greek culture. Even more interesting is the way the races were started. In the same way that NASCAR uses a pace car to get cars up to starting speed before checkered flag starts the race, the Ancients used mechanical devices to accomplish a similar task for a rolling--or rather--galloping start. The starting gates were lowered and staggered in a way so the chariots on the outside lanes began the race earlier than those on the inside. The race only began when each chariot was lined up next to each other--"keeping pace". Chariots in the outside lanes would be moving faster than the ones on the inner lanes. While flags are used in modern auto racing, mechanical devices shaped like eagles and dolphins were raised to start the race. Dolphins were lowered with each successive lap. In Rome, often the Emperor himself would start the race by dropping a white cloth called a mappa. In the end, the winners were given their awards right away. An olive wreath was placed on their head. In the Roman Empire there would be cash awards or possibly a gift of a slave for the charioteer. Fame was also part of the game, as is the case today. Scorpus, a celebrated driver won over 2000 races before being killed in a collision at the ripe age of 27. Most charioteers had a short life expectancy. The most famous driver was Gaius Appuleius Diocles who won 1,462 out of 4,257 races. When Diocles retired at the age of 42 (after 24 years) his career winnings 35,863,120 sesterces--approximately 15 billion dollars today--making him the highest paid sports star in human history. A couple of more interesting differences: Women weren't permitted at the races as they are today; and while today's largest NASCAR racetracks hold under 150,000 spectators, the Circus Maximus in Rome held 250,000! Gentlemen, start your... er... feed your horses! Go! --Jerry Finzi Copyright 2017, Jerry Finzi/Grand Voyage Italy - All Rights Reserved

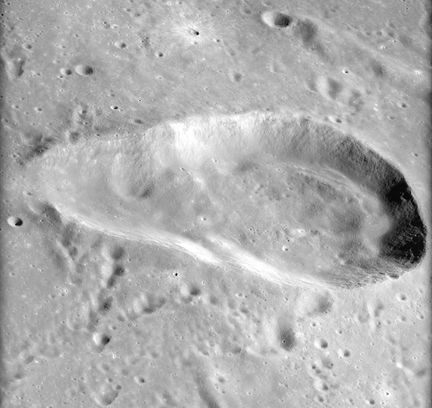

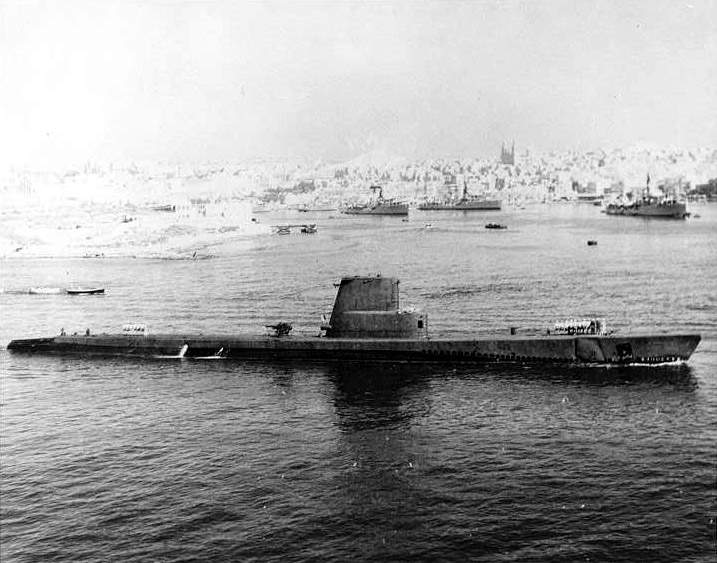

Evangelista Torricelli was born Oct. 15, 1608 in Faenza, Romagna. He was an Italian physicist and mathematician who invented the barometer, a device that measures atmospheric pressure, commonly used in forecasting changes in the weather. The catalyst for inventing the barometer was spurred on my a suggestion by Galileo that Torricelli use mercury in place of water for his vacuum experiments. After reading his papers in 1641, Galileo invited Torricelli to Florence, where he became the aging astronomer's secretary and assistant during the last three months of Galileo’s life. After Galileo's death, Torricelli was appointed as his successor as professor of mathematics at the Florentine Academy. Two years later, pursuing the suggestion by Galileo, he filled a glass tube 4 feet (1.2 m) long with mercury and inverted the tube into a dish. He observed that some of the mercury did not flow out and that the space above the mercury in the tube was a vacuum. Torricelli became the first man to create a sustained vacuum. His observations proved that the variation of the height of the mercury from day to day was caused by changes in atmospheric pressure. He never published his findings, however, because he was too deeply involved in the study of pure mathematics. Since atmospheric pressure also changes with altitude, Torricelli's barometer also could be used as an altimeter. Torricelli died Oct. 25, 1647 in Florence at a mere 39 years old. As a further honor, Torricelli had both a crater on the moon and a submarine named after him... Play the video to see how Torricelli's experiment worked.

Unlike Henry Ford's factory line, which went from one end of his huge manufacturing facility to the other, popping out a finished car at the end, Fiat did things a bit different, to say the least. The Lingotto building in Milano was designed by architect Matté Trucco, had five floors, with raw materials going in at the ground floor, and cars built on an assembly line spiraled up through the building. Finished cars emerged at the top level and immediately were driven on the rooftop test track to ensure quality control. Built between 1916 and 1923, it was the largest car factory in the world at that time. This factory was closed in 1982, but public outcry over a plan to demolish the structure caused it to be redeveloped into a more modern use. The structure was turned into a modern public complex containing a shopping mall, concert halls, theater, convention center and a hotel. The work was completed in 1989. The test track was saved, and can still be visited today on the top floor of the shopping mall and hotel. A scene from the film, The Italian Job from 1969 with Mini-Coopers and police in a car chase on the Fiat rooftop track, curiously, they drove Mini-Coopers and not Fiats. --Jerry Finzi

If you CARE, please SHARE. Ciao!

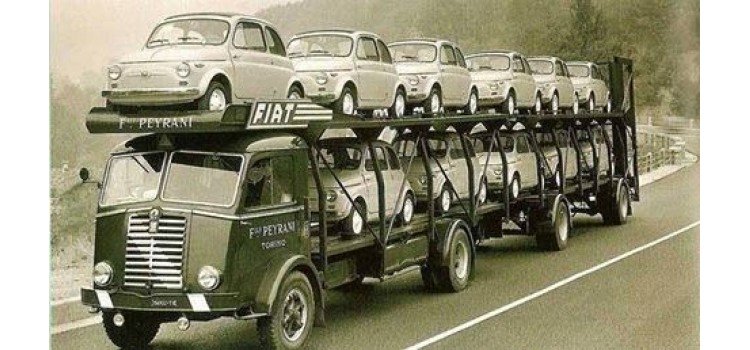

On July 4, 1957 the first of the Fiat 500 Nuova were introduced to the public in Turino. In a massive public relations stunt, a procession Fiat 500s, each with a beauty queen on board, drove from the factory. At the same time driving in Rome a similar procession to St. Peter's Square.

Big brother, Seicento with a the smaller Cinquecento parked just behind it Big brother, Seicento with a the smaller Cinquecento parked just behind it

Coming to be known as the Cinquecento (cheen-qway-CHENT-o... Italian for "500"), its sales were slow in the beginning, because prior to its release, the water-cooled Fiat 600 (the Seicento, produced from 1955 - 1969) was enormously popular and Fiat didn't want to swamp the market with yet another model. Eventually, they produced nearly 3.5 million copies of the Nuova 500 until 1975.

TRIVIA: Fiat is an acronym for Fabbrica Italiana Automobili Torino

The first Nuova 500 was referred to as "N" model, with backwards opening "suicide" doors, no heater, fixed rear side windows and a fabric roof opening all the way to the rear. It was spartan, to say the least--and tiny--a mere 9'9" long. It was designed as an every-man's car... a family car for essential trips around town.

1957 Marinella, for resort transportation 1957 Marinella, for resort transportation

A close cugino (cousin) to the original Fiat 500 and 600, the Multipla (commonly known as the Seicento Famigliare--"Family 600") was primarily based on the Fiat 600 and sat six people in fairly small size. The driver's compartment was moved forward over the front axle, effectively eliminating the front storage trunk, but giving it a modern minivan appearance. It could be configured with either a flat cargo area behind the front seats or a choice of one or two bench seats. This popular people and cargo mover was a very popular taxi in many parts of Italy up until the 1970s. There even was a beach car version called the Marinella created by car design shop Carrozzeria Ghia.

I personally love practical cars, and loved driving the new Fiat 500L (called the "Large" in Italy) during our Voyage through Italy, although I am certain the U.S. version has a better transmission. We've owned three minivans in our family and would love to see a new version of the Multipla brought to the U.S. in a family minivan configuration. Fiat did introduce a modern version of the Multipla from 1998 to 2010, but despite acclaim for it's bold design (amazing visibility due to huge windows) slack sales outside of Italy doomed the model.

The legendary automobile coach builder Ghia (of Volkswagon Karmann Ghia fame) also created one of my all time favorite cars based on the Cinquecento... the fun-sounding Jolly. The chassis was made by Fiat but everything else was built by Ghia. The little car with a surrey on top was really designed for the rich--as a small car that could be hoisted on and off mega-yachts tooling around the Mediterranean. Oil magnate, Aristotle Onassis (Jackie Kennedy's second hubby) owned one and President Johnson rode around his Texas ranch his. It was a perfect seaside runabout to go from marina to golf course to dinner and back to the marina... while keeping the sun off of the heads of the rich, famous and film stars. Since mostly the elite usually bought them, each one was customized. Besides the canopy, it had no doors and wicker seats. Very cool car... nowadays going for a couple of hundred thousand dollars at classic car auctions. Supposedly, there are less than 100 left in the world.

Of course, this brings us to the current incarnation of the Cinquecento... the Fiat 500 (Type 312). Introduced in 2007, its new styling is reminiscent of Fiat's original 1957 Nuova. It holds four passengers fairly comfortably with a front rather than rear engine, has front wheel drive, and is offered in a three door hatchback and two door cabriolet styles. The newest addition to the U.S. market came in 2016 as a nod to the past Spider series with the Fiat 124 Spider--a joint venture with Mazda, using the new Mazda MX-5 platform. Car manufacturers make strange bedfellows lately... after all, who would have thought that Chrysler would now be owned by Fiat?

It was great to see Fiat's return to the American market after 27 years... I owned a red Fiat 128 station wagon back in the Seventies during the oil embargo and odd-even gas rationing days. I got 30 miles to the gallon while most back then got about 6. I recently did a test-drive the new Cinquecento and love it... although being a tad small, even for our "We Three" family. It's drive didn't feel small, at all. The advent of the Fiat 500L and 500X go even further in changing all that. These are bigger, four door models with plenty of room for small families. Lucas loved having a raised rear "theater" seat in the "L" while we traveled through Italy... giving him much better views. We also liked having the glove box drink chiller--a very welcome thing in hot Italy.

All in all, the Fiat 500 was--and still is--one of the most important, practical designs for people movers on the planet. When you live in a country like Italy with winding roads, limited parking spaces, narrow streets in most villages and the price of fuel always grabbing cash out of your wallet, the ubiquitous Cinquecento simply makes sense... Bravo Fiat! Bravo Italia! --Jerry Finzi If you CARE, please SHARE... Ciao! |

On Amazon:

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed