|

Nowadays we buy all sorts of toys for our children, starting them off with the simplest ones: balls, pull-toys, rattles and such. When Lucas was a baby boy, his favorite was a cushy soft ball with a rattles inside--"Shakey Shakey"--he always like to squeeze it tight and shake it. Then there was his spinning top, the kind you pump down on for it to spin. Lots of twirling colors delighted him. Then there was his bouncer, with it's assortment of colorful gizmos for him to touch, hear and chew on. And at 13, he still sleeps with his oldest and dearest friends... his plush "Cushy Bear" and "Moo-Cow". Kids were always kids... even in the ancient world parents gave their kids toys...

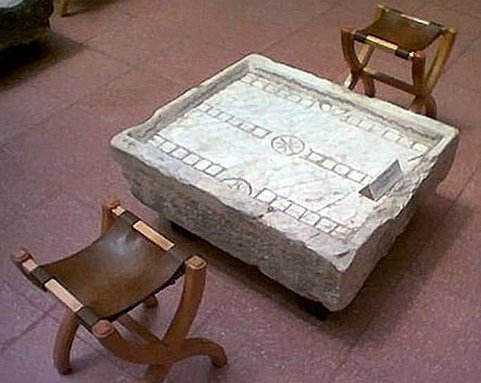

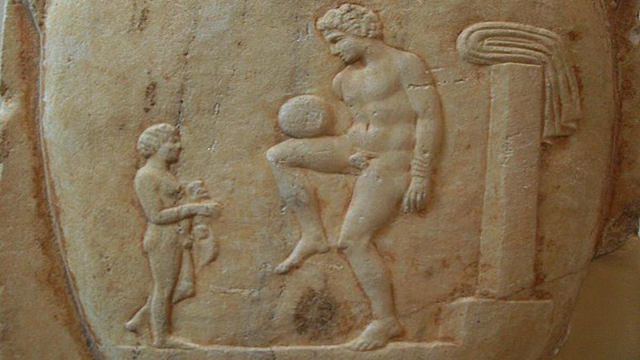

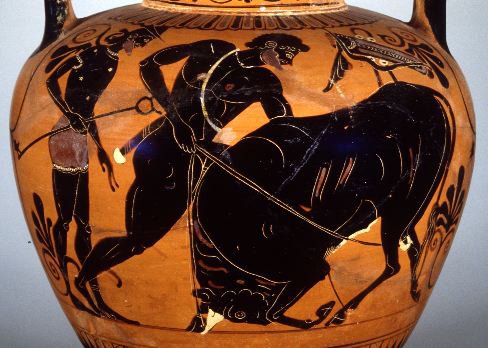

Of course, many first toys used by plebeian children were made from things found in nature: rocks, sticks, clay, acorns, pine cones, or vines or husks made into primitive dolls. Sometimes childhood fun is as simple as that. A game called Battledore, resembling badminton, used flat paddles hitting pine cones back and forth, or cork balls with feathers stuck into them used as the shuttlecocks. Pebbles could become a game with the dirt becoming a game board or a place to draw with a pointy stick. Just as today, one generation of children passed along ludos in plateis (street games) to the next. And of course there were dolls... made from fabric and stuffing, carved from wood or made from terracotta. Modern parents would have a hard time picturing a child cuddling up to a terracotta dolly. I wonder how many must have been broken in a tantrum during the Terribili Due (the Terrible Twos). For the toddlers, there were pull-toys made of terracotta or wood in all sorts of animal shapes. Some kiddies played with horses and chariots, just as modern kids might play with toy cars. One can imagine a young boy playing the part of the latest charioteer champion. As a boy got older, he might build a little cart to hitch a mouse to. As a kid, I remember putting my hamster behind the wheel of a remote control Model-T Ford model that I had... I loved watching him with his little paws on the steering wheel, going round and round. He seemed to like it, too. A mouse-drawn cart sounds like lots of fun, too.  Roman pig's bladder football Roman pig's bladder football The older boys and girls had outdoor toys... sticks and hoops, balls, yo-yos, swings, bow and arrows, sling shots, hobby horses, marbles, and games similar to kick-the-can, hide-and-seek and tag. And you can imagine some great racing games using toys with wheels on them... "My chariot can beat your ox cart! I'll bet 5 marbles that I can!" Of course, all a kid needed to do was have a ball and a stick and he'd make up a game. If he didn't have a ball, a rock or pine cone would do. When I was a boy we played stickball with an old broomstick and a cheap 10 cent pink ball called a Spalding (Spaldeen, we called it). Even thousands of years ago kids had games similar to field hockey or baseball or basketball. Borrow a basket from Mom (while she wasn't looking), start tossing some pine cones, and the fun would ensue. Sling shots--the same type David used to slay the Giant--came in useful to teach young boys how to hunt. And swimming was enormously popular for Roman boys. They would either go to a special swimming pool (Roman baths were too shallow for "plunging") or to the river. Boys were taught to swim as part of their formal education. Games were popular too, just like today. One of the most common was tic-tac-toe--played just as we do today, with Xs and Os. Some were carved into walls while most games were just scratched into the ground for temporary fun. Another similar game, Rota, was played with small stones on a layout that looked like pizza cut into 8 slices.  Box with sliding lid (missing) containing 2 dice Box with sliding lid (missing) containing 2 dice Cube shaped dice, as we know them, were around for at least 5000 years. There were always dice games, many for children and others for adult gambling. A precursor of dice, and a popular game, in and of itself, is Knucklebones (also called astragaloi), a game usually played with five or ten small bones. In ancient times, the "knucklebones" were the the actual knucklebones (astragalus--small ankle bones) of a sheep, although there are ancient "bones" made from precious gems, bronze or glass. The oldest version of a knucklebones game determined a winner depending on which side of the knucklebones landed facing up. (Both sides are distinctly different in shape.)  Knucklebones and Roman Dice Knucklebones and Roman Dice In another, the bones were tossed up in a manner similar to modern Jacks, with one knucklebone tossed into the air, and the player trying to pick up as many others as possible while it is airborne. Curiously, differently shaped bones would be worth different points. In another Roman game called Tali, the knucklebones are marked as dice are, with dots representing numbers--the resulting toss gives a player a hand to beat, similar to dice or playing cards. You can actually purchase Knucklebone pieces on Amazon.  Tabula shaking cup and dice Tabula shaking cup and dice There was also a game called Tabula that was very similar to backgammon of today, except it was played with three dice, but for most part, dice games of chance were left to adults--especially soldiers--for gambling. Still, boys have to learn the game from someone. I can imagine a father teaching his son how to play, as I've taught Lucas to play backgammon. An interesting fact is that when Greek and Roman girls, "came of age" (at 12-14 years old) it was customary for them to sacrifice the toys of their childhood to the gods. On the eve of their wedding, young girls around fourteen would offer their dolls in a temple as a rite of passage into adulthood. And yes... girls were married off after the age of 12.

Here are some other facts about what childhood was like in the Ancient World:

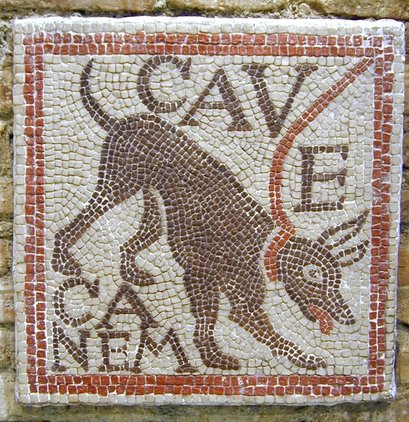

Bronze toy mouse Bronze toy mouse When a kid got bored with his toys, he could always spending time with his best friend, Il Cane, who might answer to Craugis (Yapper) or Asbolos (Soot) or Scylax (Puppy). The ancient Romans loved using Greek names for their pet dogs. Romans were great dog-lovers and had several popular breeds to choose from: hunting hounds, ratters and other small breeds that were bred for companionship and to keep their masters' feet warm in bed. Romans also loved birds, evidenced by various types shown domestic scenes in frescoes and mosaics. The odd thing is, cats were not liked in the Roman world, and even though might have helped rid them of rodents, were themselves thought of as pests. (Perhaps it's the Roman in me, because I feel the same way when roaming cats spray and stink up in my garden.) There are also mosaics showing children with pet goats hitched to child-sized carts, and even mice harnessed to miniature toy wagons. Unlike Italians of today, who tend to take a more practical view of animals, Romans loved their animals dearly. For example, modern Italians don't like to spend a lot of money on their pets--not even vets. Ancient frescoes and sculptures show Romans treating their pets as if they were members of the family. The dogs must have felt the same way, becoming protectors of their families, as illustrated by the many Cane Cavem (Beware of Dog) mosaics found at the portals of Roman homes. Here's a great batch of modern Roman toys (on Amazon) that your little ones can play with while they imagine life in ancient Rome...

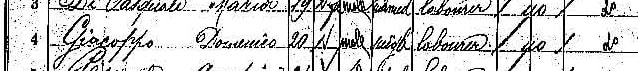

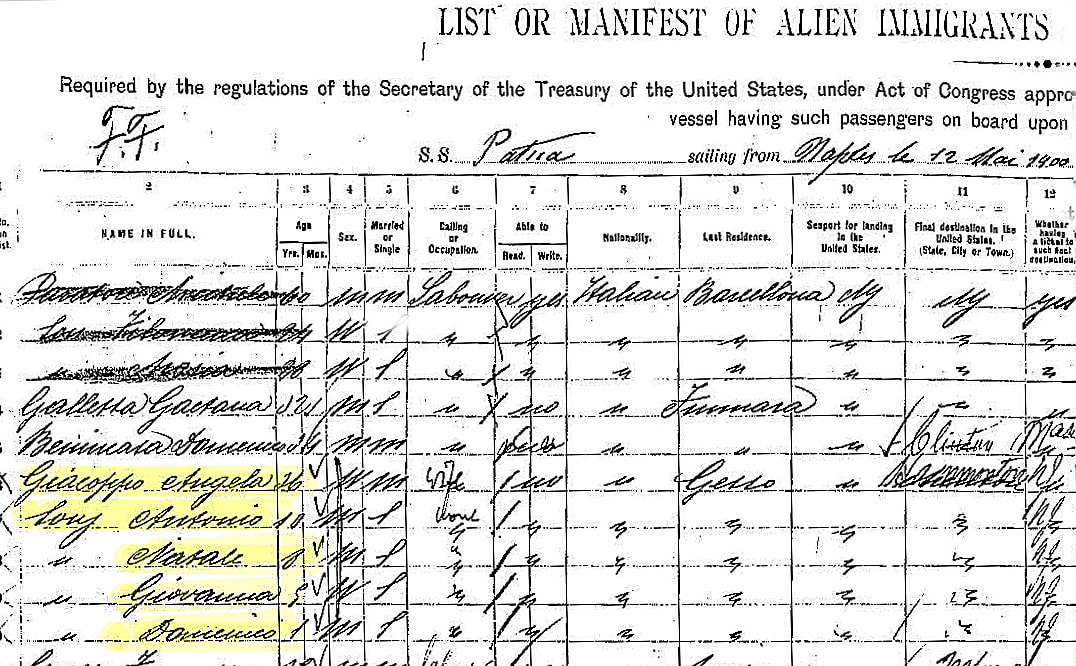

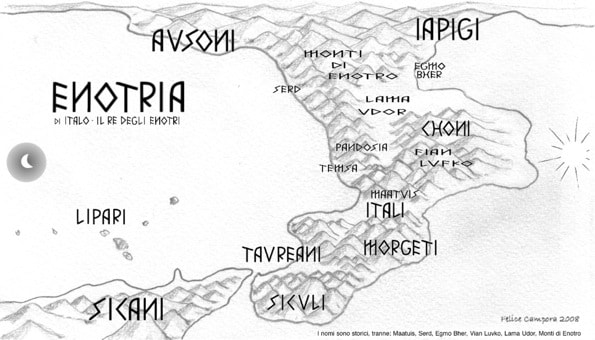

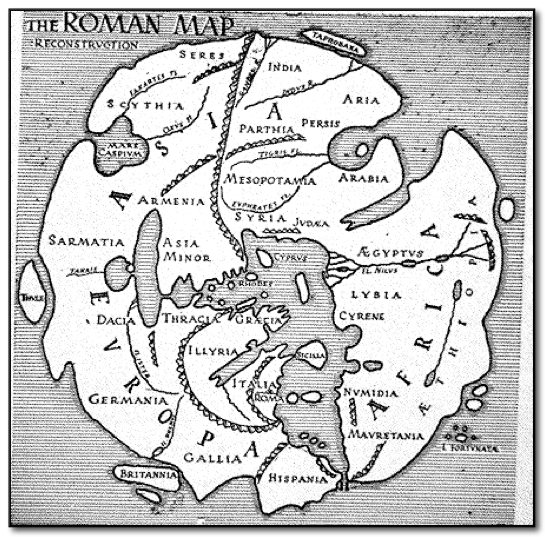

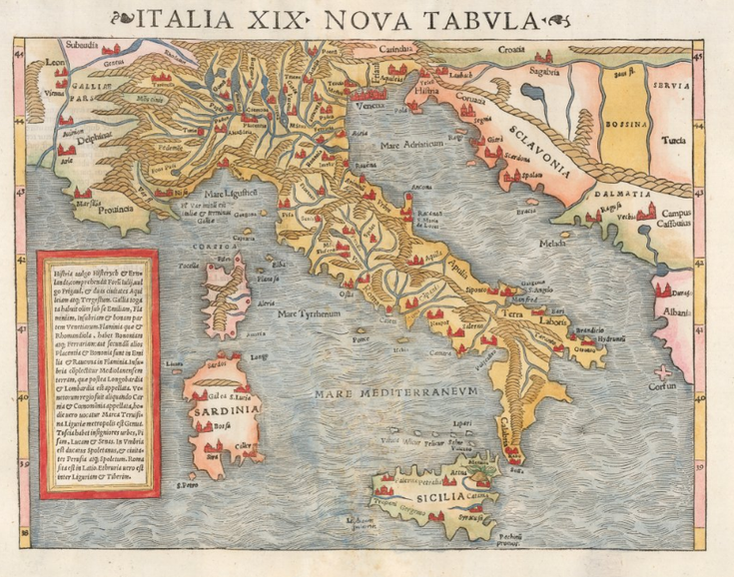

Jill Biden might not be a full blooded Italian descendant, but there are many Italian-Americans who are only half Italian yet still identify themselves as "Italian" when asked. For instance, I'm a first generation Italian-American with both of my parents being Italian, but my wife has an Italian father and Polish mother. The interesting thing is, she has never really identified as Polish-American since most of her cultural influences growing up were from the Italian side of her family. Even late night TV host Jimmy Kimmel (originally Kummel, from his German paternal grandfather), thinks of himself as Italian-American, since the great family influences were from the Neapolitan side of his mother's family. There has been recent talk of Jill Biden having Italian roots, but I wonder how she identifies herself when asked about her heritage. I'm certain, for politically correct reasons, her answer to journalists would be, "I'm American". Still, in my experience, having even a tiny bit of Italian blood running through someone's veins is enough for anyone to proudly embrace their Italian roots. Who wouldn't want to be Italian? Jill Tracy Jacobs Biden is half Italian. Her grandfather, Domenico Giacoppo emigrated from the small Sicilian village of Gesso, escaping the poverty and chaos created by recent earthquakes in the region of Messina. He later changed his name, in an attempt to Americanize it, to Jacobs. Jill's father, Donald Carl Jacobs (1927–1999), was a U.S. Navy signalman during World War II, who afterwards used the G.I. Bill to attend business school, eventually becoming head of a savings and loan institution in Philadelphia. Her mother, Bonny Jean Godfrey Jacobs (1930–2008), was homemaker of English and Scottish descent. One of Biden's distant Sicilian cousins, Caterina Giacoppo offered an invitation that has gotten a lot of press lately... “Jill, I’m here, my house is open for you, as is our entire Sicilian village of Gesso where your grandfather came from. Please do come visit us next time you travel to Italy.” Gesso is a tiny, close-knit community with only 600 inhabitants in the province of Messina. She went on, "I would be very happy if Jill came here ... I would like to meet her. We are ready to have a nice party all over the commune. If you come, I'll cook you baked pasta, roasted braciolettine arrostite and other local delicacies such as eggplant parmigiana, pasta alla 'ncasciata and cannoli filled with fresh goat ricotta, which is one of my specialties" Flavors of Gesso, Sicily Pasta alla 'Ncasciata is the local, Messinese version of baked pasta with eggplant and caciocavallo cheese. Braciolettine Arrostite is from the Arabo-Sicula cuisine, a mix of Arab and Sicilian flavors. Similar to beef brasciole, it's charcoal grilled with a stuffing of currants, pine nuts and pecorino cheese. Will we be seeing pasta and pizza nights at the White House soon? Only time will tell, but as far as we're concerned, Joe Biden is more than just an Irish-Catholic... he's Italian by sheer association! The evidence is clear since his go-to menu for many past fund-raising dinners includes a caprese salad, angel hair pasta pomodoro, raspberry sorbet, and biscotti. Good luck to them both! --Jerry Finzi  The name Italy (in Italian, Italia) evolved from variants of different names used in the ancient world as early as 600 BC in what we know today as the Italian peninsula. Historians are still researching its origins, but "Italia" surely evolves from Oscan word Víteliú (spoken by the Samnites), meaning "land of young cattle". A modern variant is vitello, the Italian word for calf or veal. In Roman times, vitulus was the word for calf. The ancient Umbrian word for calf was vitlu. Coins bearing the name Víteliú (𐌅𐌝𐌕𐌄𐌋𐌉𐌞) were minted by an alliance of several Italic tribes: the Sabines, Samnites, Umbrians and others who competing with Rome in the 1st century BC. Another theory is that the name stems from the Greek Italos, a legendary king of the Oenotrians, people of Greek origin who inhabited a territory from Paestum in the Campania to southern Calabria, among the earliest inhabitants of Italy. Italus was supposedly the son of Penelope and Telegonus, a son of Odysseus. It was both Aristotle and Thucydides who first told of Italus being who Italy was named after. The Greeks gradually came to apply the name Italia to a larger region covering most of Southern Italy, but it was during the 1st century BC that Augustus expanded the name to cover the entire peninsula including the Alps. The Greeks referred to these people as Italoi. Under Emperor Diocletian the Roman region called Italia was further expanded to include the islands of Sicily (including the Maltese archipelago), Sardinia and Corsica. Another reason for the name might come from the Greek word Aethalia, meaning "land of fog and smoke", referring to its many volcanoes. Mount Etna gets its name from the same etymological root. The Holy Roman Empire adopted the name Italia to describe its own territories in the central peninsula, and afterwards, the name was used to describe virtually the entire peninsula. In Middle English, the lands were called Italie. Later, in the 14th century, Dante described "Italia" as a land including lands from the Alps to the tip of the Italian boot, and including the islands of Sicily. The last theory intrigues me the most...

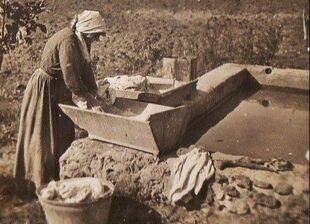

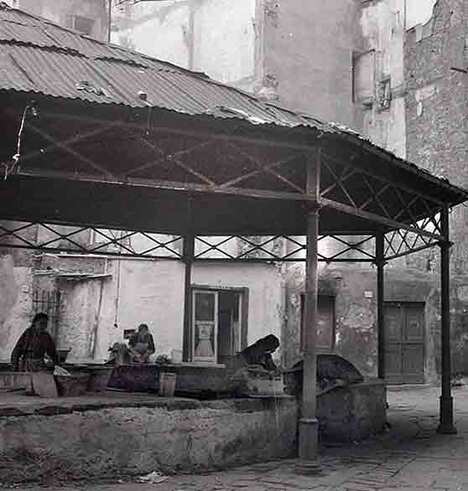

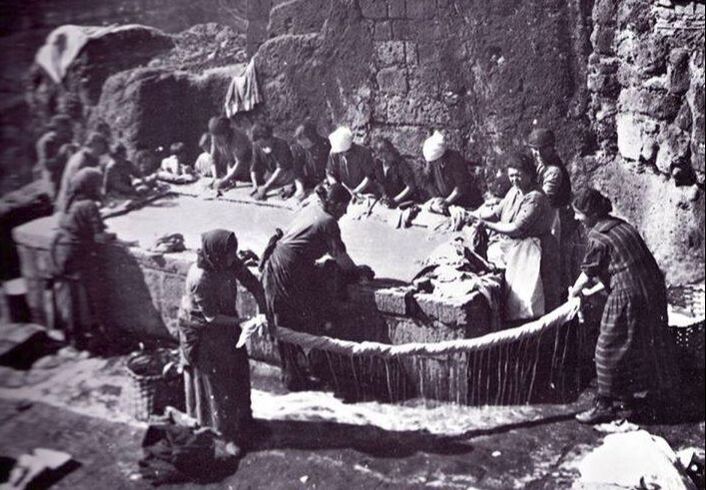

Eurystheus ordered Hercules to travel to the End of the World and bring him the cattle of the monster Geryon. Hercules succeeded in stealing the cattle but had enormous difficulty bringing the herd back to Greece. In Liguria, two sons of Poseidon, the god of the sea, tried to steal the cattle, so he killed them. At Rhegium, a bull got loose and jumped into the sea, swimming all the way to Sicily and then made its way to the neighboring country. The native word for bull was "italus," and thereafter this country came to be named after the bull. Perhaps this, stubborn, strong-minded bull is a perfect image for the naming of this amazingly resilient and tough country. Italia, Aethalia, Italie, Víteliú... and of course, the current day Italy is a never-ending source of history and amazing stories. --Jerry Finzi  My first memories of my mother doing the wash was of the squishing, splashing and grinding of our old white enameled motorized washing tub in our cellar. It had rollers stuck on top to squeegee most of the water out of the clothes, getting them ready to hang out to dry on our clothes-line overhanging our back yard garden. I often had the job to "take in the clothes" from the line. In summer I loved doing this, hanging out the window and pulling the line closer on the pulleys as I worked, and afterwards nuzzling my nose into the sun-warmed towels and shirts, sucking in the freshest smell imaginable. In winter, I would pull in cardboard-like, frozen clothing... pants and shirts looking as if someone was flattened by a steam roller. The towels would be stiff as a large baccala dried fish. As modern conveniences developed, my mother got a washer and dryer in the basement of her new suburban house. Even when she was well into her eighties, I remember visiting and catching her, moving one step at a time, bringing up a basket of laundry from the cellar, all folded neatly and smelling almost a nice as when we sun-dried them. She was a tough lady. Her mother was even tougher. In her Hoboken, NJ apartment, she washed her clothes in a sink using only a washboard. As I write this, I'm listening to be beep-beeps and musical chimes produced by our front load modern washer in our second floor laundry room. It's nearly effortless, allowing my wife Lisa to drop a load of wash as she heads up to her third floor office. OK, I know... I should do the laundry more often. Nowadays, doing the laundry is not just women's work.  Hauling water Hauling water Le Lavandaie of Italy's Past When we complain about how hard it is to do household tasks, I often think of how our Italian ancestors dealt with the hardships of everyday life. Looking at historic photos of the lavandaie (washerwomen) of Italy's past, I consider how hard Italian women had to work at cleaning their cloths. Early on in history, the contadina (country woman) would wash clothes in the nearby river, on her knees, regardless of season or weather. They would bring a wooden washboard to the river, some of these were very wide, offering a communal laundering experience. Some households had their own wooden troughs with a washboard built-in, but water would still have to hauled from the river or local fountain in order to use it.  It wasn't until 1897 that the first public lavatoio (wash house) was built in towns and villages around Italy. Some had roofs with open sides--similar to market structures--to keep the women out of the sun and rain. Many were built near existing streams, and were designed to direct the fresh running water through a trough. Still others had plumbing and elevated wash tanks, allowing women to stand while they washed clothes. What a luxury this simple change must have been! At the bare basics, a lavandaie needed troughs or tubs where fresh water ran through, and an inclined concrete or stone ramp where they could soap up and agitate the clothes and sheets with a two-handed motion similar to kneading dough. Then they would slap the clothes on the ramp to rid them of suds, dirt and odors. They used solid soap, often made locally as a by product of the slaughtering process. White fabrics, especially sheets, needed to be bleached--a bit of a complex process. The day before, sheets were soaked in boiling water with wood ashes (the bleaching agent, called ranno) and bay leaves, lavender or rosemary (adding a fresh scent). To dry, first the sheets were beaten and then it took two women to wring them out due to the heavy, waterlogged weight. Both clothing and sheets were hung to dry in the sun. Still today in modern Italy, hanging clothes in the sun is the preferred way to dry clothes and while Italian households today might have a washer, they rarely have a clothes dryer. Some women called bugadere did the laundry for people who could afford to pay for the service. This was a profession for women only, and only for single women, since most men wouldn't want their wives touching other peoples' dirty laundry. As you can surmise, this was considered a lowly profession. Housewives who did their family's laundry would go home when finished, but the bugadere was at the lavatoio all day long. Some of these "professional" washerwomen stayed at the village lavatoio and women would bring their laundry to them for washing. Others had clients and went to homes to pick up the laundry, carrying the heavy loads in jute bags (often on their heads). Each client's laundry was identified with a different color ribbon tied to each bag because writing a name on each would have served no purpose since most were illiterate. You can often find a woman''s profession listed as "washerwoman" on some Ellis Island ship manifests. If you find a washerwomen in your history, be proud. That must have been a tough way to earn a little money to contribute to the welfare of their families. Washing Methods and Materials There were various detergents used by lavandaie. The most common and also the least expensive was the so-called ranno, used both for for degreasing and bleaching. The technique involved filtering hot water poured over wood ash through an old linen sheet draped as a filter over a large bucket. Underneath this ash filter were the previously washed fabrics to be bleached. Many lavatoio also contained a large hearth with a large suspended cauldron to heat water for the ranno bleaching. In later years, de-greasing was accomplished by the use of sodium carbonate (similar to baking soda); lye solutions, used both for washing and whitening; Varecchina, for bleaching and stain removal; during the first rinse or ranno, crushed eggshells were added; indigo was also added as a blueing agent; in the final rinsing, lavender, bay leaves or rosemary were added to provide sweet or fresh scents; as bar soap became available it was also used, often grated into smaller pieces that could be sprinkled on clothes as they were washed. --Jerry Finzi Copyright 2020, Jerry Finzi/GrandVoyageItaly.com - All Rights Reserved In the video above, these ladies are seen adding wood ash to their tub to start the bleaching of their sheets. School boys hosting a historic demonstration by these lavandaie. A traditional song about washerwomen.

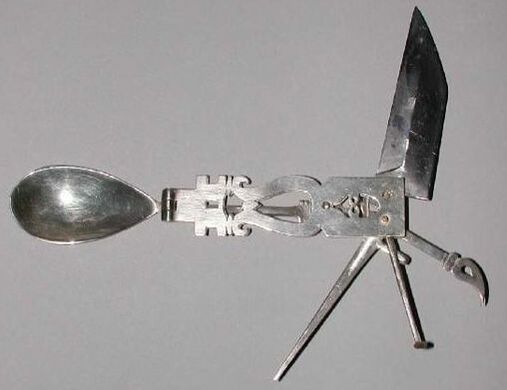

A modern public pay phone uses credit cards A modern public pay phone uses credit cards Back when I lived in France, before the advent of cell phones, this was the way you made a phone call in France, and in most of Europe... the pay phone. They were usually located in bars in both France and Italy. Remember, a bar in Italy is a not like a bar here in the States. It's a place to get your morning coffee and sweet pastry before heading off to work... a place to get the news and gossip from your neighbors... a place to get a sandwich or some sort of stuffed pizza for lunch. In the past, it was also where you bought gettoni--a special coin used only in pay phones. Shove the gettoni in the phone, hear the dial tone and dial your number... or was it the other way around? It was always a bit confusing for visitors. I do remember they worked a bit differently than American pay phones. You may still encounter pay phones in Italy, but nowadays they take credit cards. Be wary of instructions on the phone to make international calls! Even though they look official (perhaps being under plexiglass), they are scams! Smart phones are a Godsend when traveling through Italy nowadays... --Jerry Finzi We all know the Swiss Army knife with knife blades, toothpick, comb, scissors and more folding out from its case. The Swiss are fairly innovative, but this is one invention that the ancient Romans might have beat them on. This example of a Roman multi-tool was used nearly 2000 years ago and discovered in an unspecified Mediterranean site. This intricate design dates from around 200 AD and is made of silver, with an obviously rusted iron knife blade. It has implements that fold out for use: knife, spoon, fork, spike, spatula and small tooth-pick. Some believe this was an eating and grooming instrument carried by Roman troops, but more than likely, because it was made of silver, it was used by a higher ranked official of the Legionnaires or possibly a political figure--definitely a wealthy Roman traveler. It is in the Greek and Roman antiquities gallery at the Fitzwilliam Museum, in Cambridge, England. --GVI Were the ancient Romans ahead of their time? The famous Lycurgus Cup in the British Museum might be proof that they were indeed very advanced in the sciences, especially in the field of Nanotechnology. The 1,600-year-old glass goblet does something very magical: It changes color from jade-green to blood-red depending on the direction of its illumination... with the light source from the front, the goblet appears green, from the rear it changes dramatically to red. This is called Dichroic behavior. The Roman craftsmen who created this work of art either knew about the science behind it, or stumbled unknowingly onto its special characteristics. As they might have put it, felix accidente, a happy accident. The Romans may have been the first to discover the colorful potential of nano-particles by accident, but they seem to have created the world's most perfect example of the phenomenon. The Artistry of the Chalice The Lycurgus Cup is also a very rare example of a Roman caged cup, or diatretum. The glass has been painstakingly cut and ground back to leave only a decorative "cage" on the surface with extreme undercutting. Instead of the more common abstract, geometric design, the Lysurgus Cup contains beautifully detailed human figures. It shows the mythical King Lycurgus, who attempted to kill Ambrosia, a follower of the god Dionysus (Bacchus). She was transformed into a vine that twined around the enraged king, killing him. Dionysus and two followers are shown taunting the king. Such figures on a caged cup are otherwise unknown. History of the Cup The Cup is thought to have been made in either Alexandria or Rome around 290-325 AD, measuring 6 1/2" x 5". Judging from its excellent condition, it more than likely was never buried and was always kept as a treasure, at first in a noble Roman's villa, then in a church and later in the collections of the elite. There is also the possibility that it was recovered from a sarcophagus. The gilt and bronze feet were added late in its life--about 1800, making some think it was looted from the church during the French Revolution. It's more than likely that earlier mounts existed, but wore away with time and use. No one really knows the earlier history of the Cup. One can ponder about who it was originally created for, perhaps an emperor? The Science Behind the Chalice: Dichroism The Lycurgus Cup was mentioned in French writings as early as the 1845, but no one knew why it changed color. The British Museum acquired the Cup in the 1950s, but it wasn't until 1990 that researchers examined small broken shards under an electron microscope and discovered the secret. Whether or not the Romans stumbled into it, the artisans were truly nanotechnology pioneers. Nano-particles of gold in the glass on a microscopic level is the reason for the color change. (Gold added to glass makes red glass, as in stained glass windows). It's unknown whether the Roman artisans impregnated the glass with particles of silver and gold on purpose, or whether the glass was somehow already "contaminated" before they used it. Researchers found particles as small as 50 nanometers in diameter, less than one-thousandth the size of a grain of salt. Some think that exact ratio of the mixture of the precious metals suggests the Romans certainly did know what they were doing. This is how the technology works: When hit with light, electrons belonging to the metal flecks reflect frequencies into our eyes in ways that alter the color depending on the observer’s position in relation to the light. Was the Lycurgus Cup a Poison Detector? During the Renaissance, the ruling class believed that goblets and glassware made on the island of Murano in the Venice lagoon would vibrate and shatter when poison was poured into them. Although false--and likely just marketing hype aimed at the ultra-rich so they would pay more for glassware--perhaps this long held notion was based in some long-distant reality... a capability of cups like the Lycurgus, perhaps? Gang Logan Liu, is an engineer at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and has been focusing on using nanotechnology to diagnosis and treat disease. He explains, “The Romans knew how to make and use nano-particles for beautiful art. We wanted to see if this could have scientific applications.” Liu theorized that when a nano-treated vessel was filled with various liquids, the vibrating electrons would change the color of the glass according to the type of liquid used. The use the Lycurgus Cup to test his theory could never be allowed for fear of damaging a priceless Roman artifact. So he created this experiment: The scientists imprinted billions of tiny wells onto a plastic plate about the size of a postage stamp and sprayed the wells with gold or silver nano-particles, essentially creating an array with billions of ultra-miniature Lycurgus Cups. When water, oil, or sugar and salt solutions were poured into the wells, they displayed a range of easy-to-distinguish colors—light green for water and red for oil, for example. The prototype was 100 times more sensitive to altered levels of salt in solution than current commercial sensors using similar techniques. Were There Other Dichrioc Cups the Ancient World? Yes, it seems that the ruling class were well aware of them, owned them, gave them as gifts and drank from them on special occasions. However, only a handful of Roman dichroic glass objects are known to exist. Only 50 or so late Roman cage cups themselves exist, but even rarer, fewer than 10 dichroic glass objects have ever been found, and all of them (aside from the Lycurgus Cup) are mere fragments. Objects of such rarity with the extraordinary property of changing color would obviously be bought or commissioned by only privileged Romans. There are some ancient texts that discuss them... From Vopiscus' life of the third-century pretender Saturninus is a letter claimed to be written by emperor Hadrian (117–138) when he was in Egypt. Written in the early 4th century AD, Hadrian describes a gift to his brother-in-law Severianus in Rome: "I have sent you parti-colored cups that change color; presented to me by the priest of a temple. They are specially dedicated to you and to my sister. I would like you to use them at banquets on feast days" From the novel Leukippe and Cleitophon by Achilles Tatius (a second-century AD Alexandrian): The hero, Cleitophon, is at Tyre, where he attends a banquet given by his father on the feast day of Dionysus. During the meal, the host offers libations from an unusual vessel: "My father, wishing to celebrate it with splendor, had ... a precious bowl to be used for libations to the god ... Made of crystal... Vines crowned its rim growing from the cup itself, their bunches drooped in every direction. When the cup was empty, each grape seemed green and unripe, but when wine was poured into it, then little by little the clusters became red and dark, the green crop turning into the ripe fruit. Dionysus... was represented, near the bunches, as the husbandman of the vine and the vintner." Both of these texts describe very similar drinking vessels as the Lycurgus Cup. In the second text, you can imagine the cup from the drinker's perspective--filled with dark red wine, the outside of the cup was green. Then as the drinker lifts his glass and peers into it, the light passes through the side and it looks as if the grapes have turned red! The Lycurgus Cup was obviously a cup from Roman royalty that was treasured and cared for throughout the last 1600 years until modern scientists unlocked its secret. The Romans perhaps knew how to make and use nano-particles to create a beautiful object, but modern scientists think that nanotechnology can be useful in a wide range of scientific fields: chemistry, biology, physics, materials science, and engineering. Of course, perhaps equally amazing is the sheer beauty and artistry of the Lycurgus Cup. The capabilities of ancient Romans never cease to amaze me. --Jerry Finzi Watch the video below to see the changing colors... E questo è il fiore del partigiano … morto per la libertà! This is the flower of the partisan … who died for freedom April 25, the Festa della Liberazione is an Italian national holiday that commemorates the liberation from fascist domination in Italy. On this day you might hear the partisan song, Bella Ciao on the radio, in parades, or sung by small groups in small town piazzi all over Italy. It is the song of I Partigiani, men and women who fought against the Nazis and Fascists primarily in Northern Italy from 1943 to 1945. This is the period called La Resistenza, the Resistance. The song is set to the melody of a traditional folk song and became the anthem of the Italian resistance movement during World War II, sung by the anti-fascist rebels who fought against the atrocities of the Nazis and Benito Mussolini. The lyrics are symbolic of the sacrifices made for freedom. Each April 25 there are Liberation Day festivities throughout the country, paying tribute to those who lost their lives in in the fight to free their country.  Mussolini, the second from the left Mussolini, the second from the left In 1943, Mussolini was deposed by the King Victor Emmanuel III of Savoy. The new government signed an armistice with the allied forces, while Mussolini was helped by the Nazis, fleeing to Northern Italy where he created a puppet state. After liberating Southern and Central Italy, the Americans passed through the Apennines. Partisans became an effective fighting force against the Nazis and Fascists in the mountain towns. On April 25th, 1945 Northern Italy was at last liberated. Mussolini would be executed by Partisans after a quick, public trial near Milano within 4 days. Shot along with his mistress, Claretta Petacci, and his other henchmen, their bodies were at first laid out in Piazzale Loreto where huge crowds of Italians took turns throwing trash on them, kicking and worse. Afterwards, their bodies were hung upside-down on the rafters of the local gas station. Perhaps a fitting end to one of the monsters of modern history. However, instead of burning the body of Mussolini (as perhaps should have been done) his body was first buried, then stolen, and afterwards found and hidden secretely in a monastary for eleven years. Unfortunately (for the Italy and the World), in May 1957 the newly appointed Prime Minister, Adone Zoli, agreed to Mussolini's interment at his place of birth in Predappio in Romagna. This was for obvious political reasons since Zoli was reliant on the far right to support him in Parliament. Sadly, even today, the remains of Mussolini has become a pro-fascist shrine or sorts. For this reason, it's a very good thing that the Russians "lost" the body of Hitler. Since the Liberation, Italy has been free from dictators, although the current neo-fascist movements are a signal to never forget what history has taught us... --Jerry Finzi Copyright 2019, Jerry Finzi/GrandVoyageItaly.com - All Rights Reserved Not to be published without expressed permission.

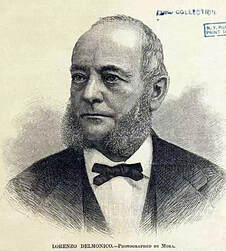

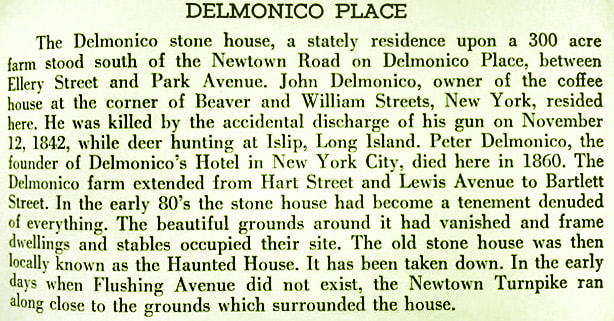

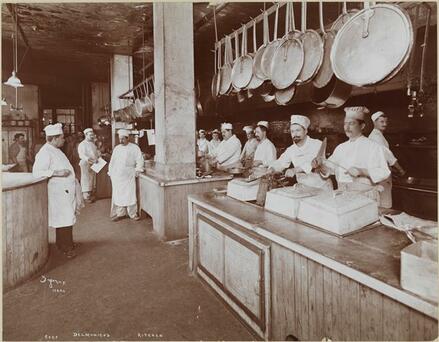

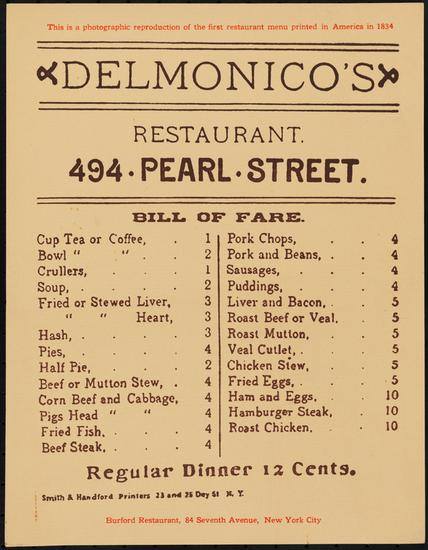

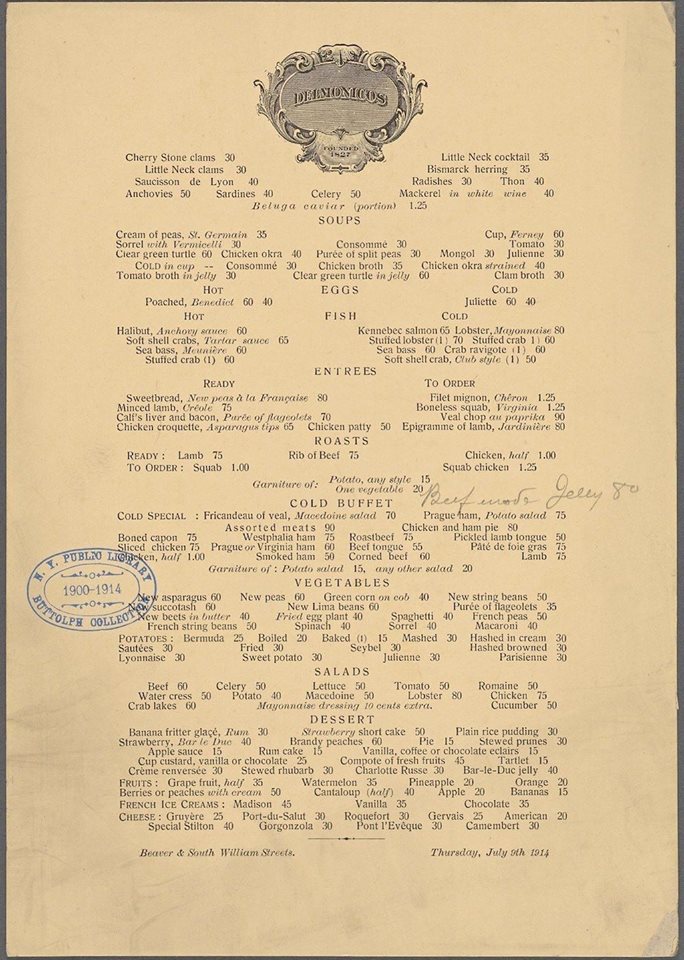

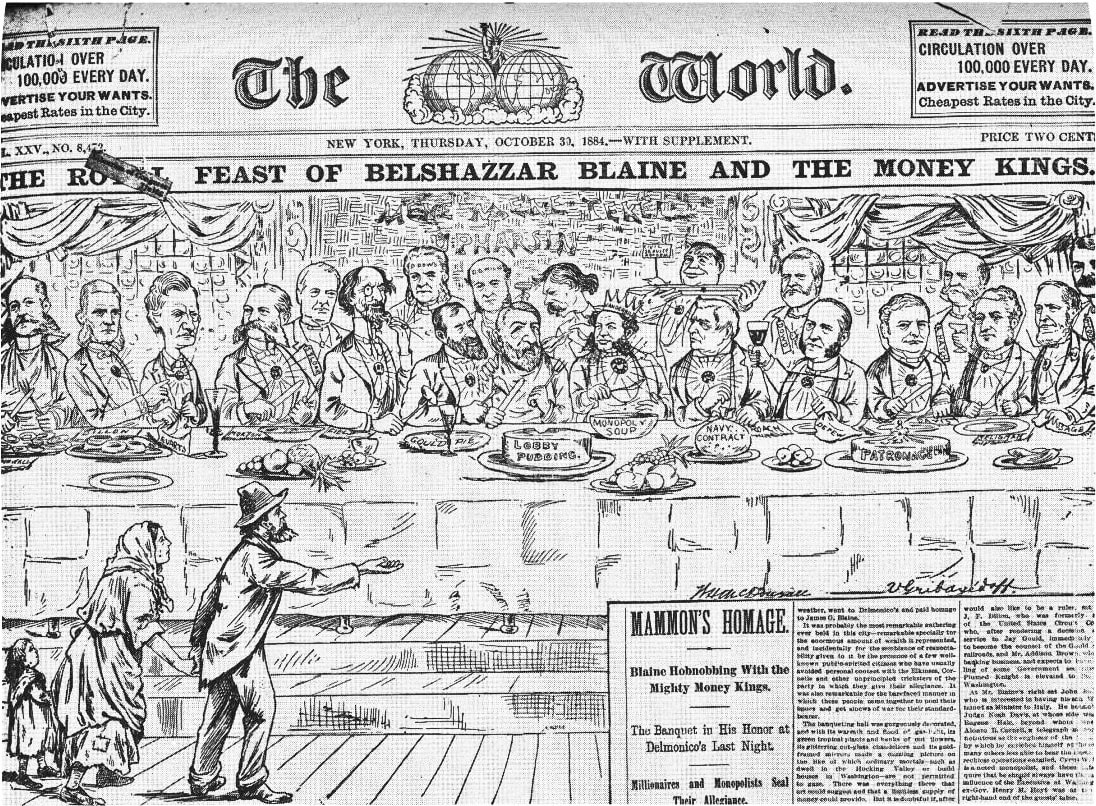

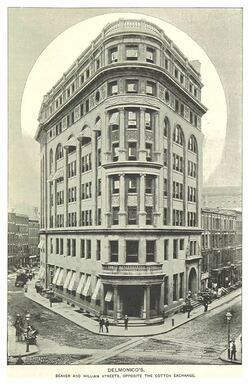

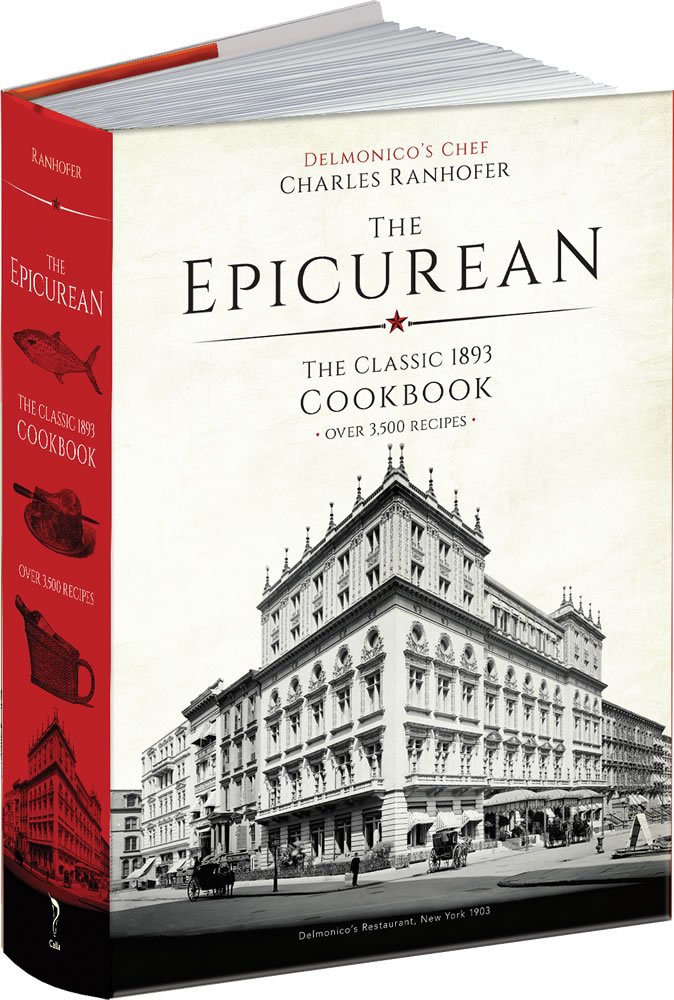

Delmonico's Restaurant in New York City was the first establishment to use the name "restaurant". They were the first restaurant to have printed menus. They were the first restaurant to offer a cookbook. They were the first restaurant to serve women sitting without men at their own table (how shocking!) Delmonico's was also the first dining establishment in America to price individual dishes à la carte, as was the custom in Paris. Before this, American inns served one price and only one dish--no menu. Everyone was charged the same fixed price whether they ate more or less than other patrons. They were also the first to open (for a while) the Delmonico Hotel, without the standard "room and board" pricing, but charged for room and meals separately. They were the first restaurant considered to be "fine dining", attracting celebrities and presidents alike. By 1862, Chef de Cuisine, Charles Ranhofer some of the most famous American dishes such as Eggs Benedict, Baked Alaska, Lobster Newburg and Chicken A la Keene (yes, not "King").Ranhofer published his cookbook, The Epicurean," in 1894.  Giovanni and Pietro Delmonico immigrated from from Ticino, Switzerland, their family roots being in the Trentino region of the Italian Alps. The brothers opened their first restaurant in 1827 in a rented pastry shop at 23 William Street, selling classically prepared pastries, fine coffee, chocolates, bonbons, wines and liquors as well as Havana cigars. In 1831 they were joined by their nephew, Lorenzo Delmonico, who was responsible for the wine list and developing its unique menu. In the coming years, Lorenzo learned every aspect of the restaurant business and was the driving force behind its impeccable standards of both product and service. The Delmonico Farm and Villa In 1834, the brothers earmarked $16,000 (worth $500,000 today) from their profits to purchase a 220 acre farm in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn. The brothers built an imposing Italian villa at the farm but primarily used the land to cultivate vegetables unknown to Americans for their restaurant, such as endive, sorrel, eggplant, asparagus, Lupini beans, tomato and artichoke. But of course, Delmonico's has become world-renowned for their aged steaks. Their first three restaurants were all destroyed by fire after which they purchased a triangular lot in Lower Manhattan and opening their landmark restaurant at Williams Street in 1893. Marketing geniuses, they claimed the two Corinthian columns at the portico were "salvaged" from Pompeii (many dispute this claim). One early and one later menu from the 19th century  They weren't attempting to serve Italian cuisine by the looks of their original menus, but to offer an upscale "European" menu, which in all parts of Europe during the 17th - 19th centuries were mainly based on Parisian fare. As their popularity with New York's elite grew, the Delmonico family opened other restaurants under the name, operating up to four at a time. In total they had opened 10, illustrating the determination of this family. The popularity of their restaurant (with its high priced menu) drew both local and national politicians, financiers such as Vanderbuilt, luminaries like Mark Twain and Italian inventor Tesla. Domenico's was (and still is) a place to discuss the financing for inventors, presidential campaigns, hob-nob with opera stars and authors... definitely now a place for the hoi polloi or common workers of Manhattan Oscar Tucci bought it in 1926 and turned it into a speakeasy during Prohibition, purchasing the third liquor license in New York after the liquor started flowing again. The Tucci family ran the business as Oscar's Delmonico until the 1980s. Various imitators opened other "Delmonico's" but were unrelated to the original family or its philosophy. Today at the landmark Williams Street restaurant, a large corporation runs a close approximation to the old world dining experience that the Brothers Delmonico first realized. --Jerry Finzi Delmonico's Italian Steakhouse |

On Amazon:

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed