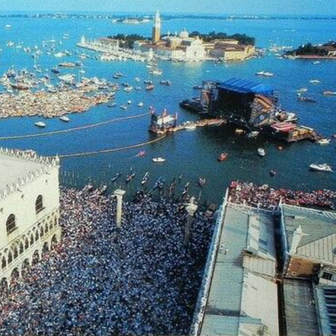

When they arrived in Venice in 1989, Pink Floyd were met by over 200,000 Italian fans, but also by a large contingent of Venetians who had no desire to see the show happen at all. The city’s municipal administrators viewed the concert as an assault against classical Venice. The concert was also stepping on traditional toes considering it was scheduled to take place in St. Mark’s square, coinciding with the hugely popular Redentore festival (the Feast of the Redeemer with fireworks from a nearby island). With Venice already threatened by sinking foundations, winter flooding, and with the memory of the St. Mark's bell tower having collapsed in 1902 (and having been rebuilt) many were concerned about the safety of the fragile historic art and architecture of the city.

Three days before the concert's July 15th date, Venice's superintendent for cultural heritage vetoed the concert, claiming that the amplified sound would damage the mosaics of St. Mark’s Basilica, while the whole piazza could very well sink under the weight of so many people dancing in unison.

The ban made concessions to allow the concert to go forward: lowering the decibel levels from 100 to 60 and performing from a floating stage 200 meters from the piazza. The concert was broadcast on TV in over 20 countries with an estimated audience of almost 100 million. The concert drew 150 thousand more people than actually lived in Venice, and even though fans were on their best behavior, one group of statues sustained minor damage and the crowds left behind 300 tons of garbage and 500 cubic meters of empty cans and bottles. And due to the fact that public porta-potties were not provided by the city, fans relieved themselves on the monuments and walls.

The concert placed tension between different political factions forcing the Mayor to resign with shouts of “resign, resign, you’ve turned Venice into a toilet.” His comrades on the city council also stepped down. The band may have taken down the city’s government, but they put on a hell of a show--one the Italian fans, and the millions of who watched from home, will never forget.

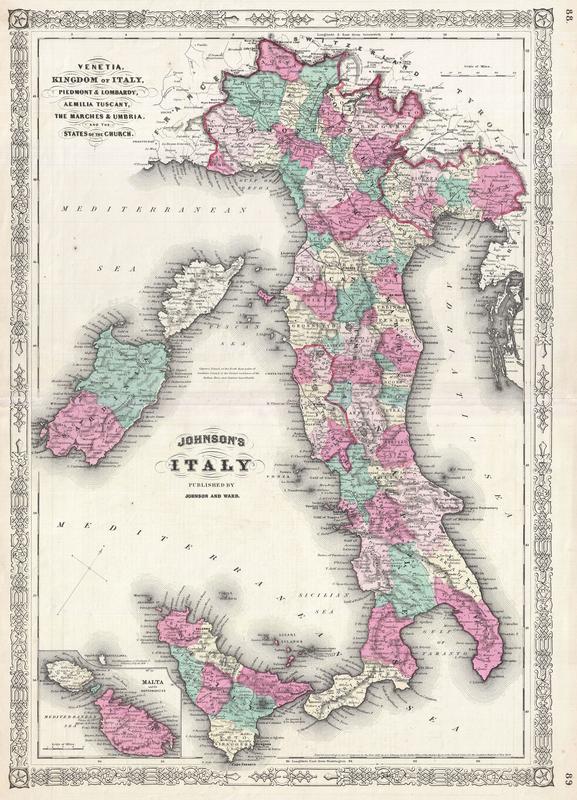

A beautiful example of A. J. Johnson’s 1866 map of Italy. Johnson first introduced this map in his 1863 atlas and it represents a substantial re-engraving of his original two part plate. Johnson's reconsideration of his Italy map was most likely related to Italy's unification in the 1860s. No longer a collection of independent states, Italy now needed to be represented as a cohesive whole. In order to accommodate this Johnson reorients his map to the northwest, allowing the boot to fill a single vertical page while leaving space to fully depict Sardinia and Corsica. In the lower right quadrant there is a inset map of Malta. Throughout, Johnson identifies various cities, towns, rivers and assortment of additional topographical details. Features the fretwork style border common to Johnson’s atlas work from 1864 to 1869. Published by A. J. Johnson and Ward as plate numbers 88 and 89 in the 1866 edition of Johnson’s New Illustrated Family Atlas .

|

On Amazon:

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed