|

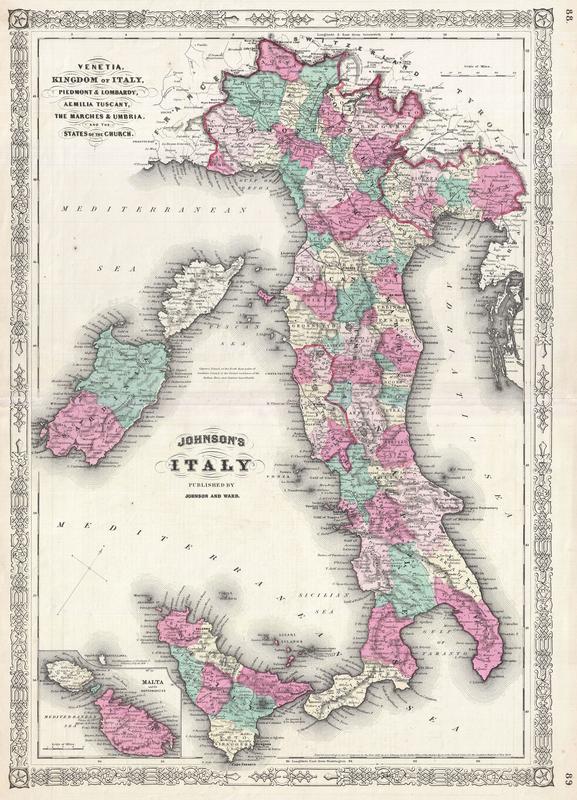

A beautiful example of A. J. Johnson’s 1866 map of Italy. Johnson first introduced this map in his 1863 atlas and it represents a substantial re-engraving of his original two part plate. Johnson's reconsideration of his Italy map was most likely related to Italy's unification in the 1860s. No longer a collection of independent states, Italy now needed to be represented as a cohesive whole. In order to accommodate this Johnson reorients his map to the northwest, allowing the boot to fill a single vertical page while leaving space to fully depict Sardinia and Corsica. In the lower right quadrant there is a inset map of Malta. Throughout, Johnson identifies various cities, towns, rivers and assortment of additional topographical details. Features the fretwork style border common to Johnson’s atlas work from 1864 to 1869. Published by A. J. Johnson and Ward as plate numbers 88 and 89 in the 1866 edition of Johnson’s New Illustrated Family Atlas .

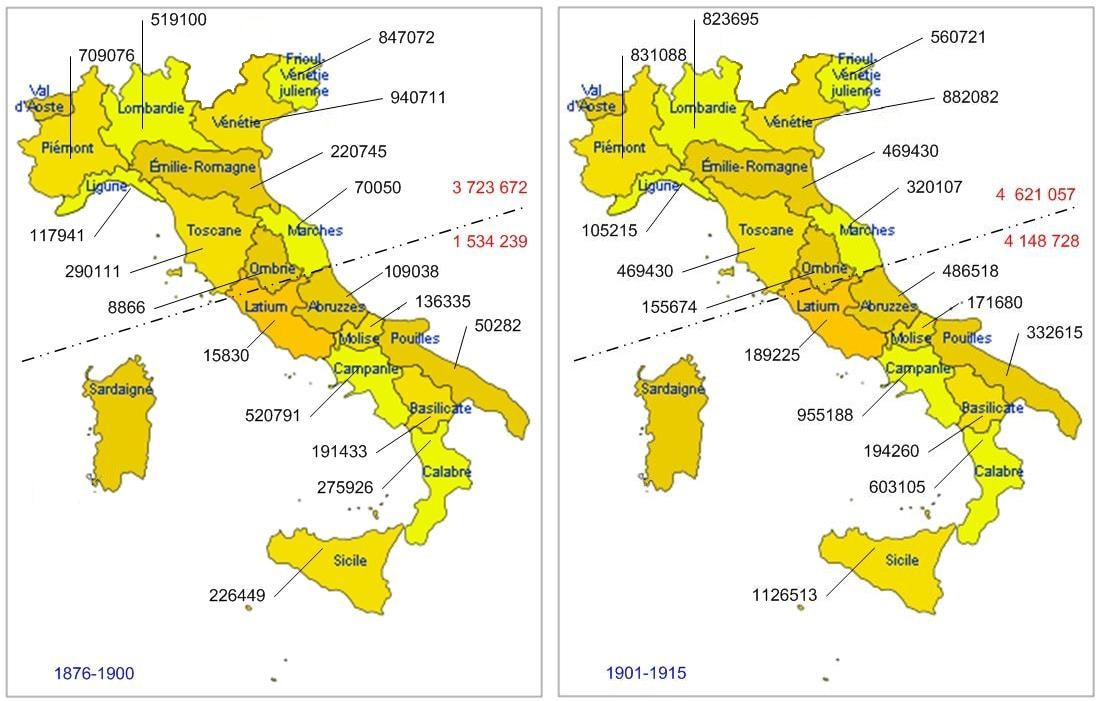

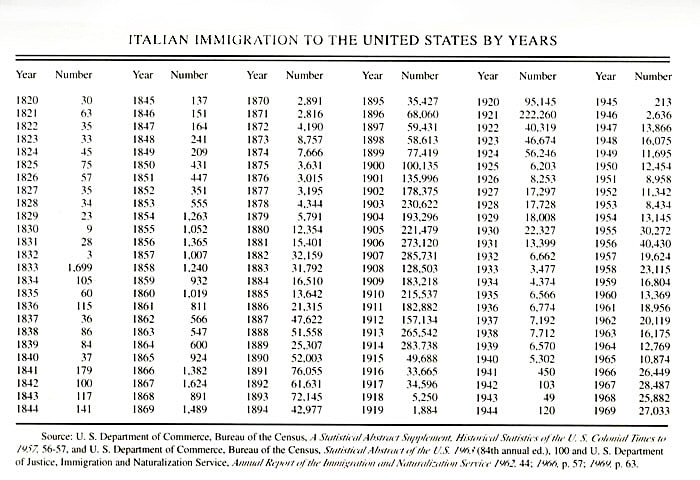

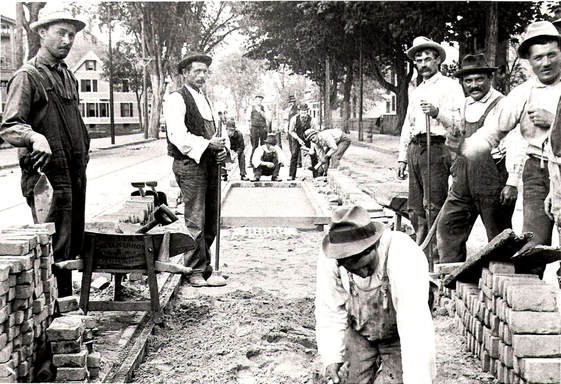

Packed like sardines... Coming to America Packed like sardines... Coming to America The Many Reasons for Coming to America Poverty was the main motivation for an Italian leaving his family and home and putting up with the hardships of traveling to America. In 1898, widespread "bread riots" plagued all of Italy, with people protesting the lack of jobs and the sudden increase in the price of wheat and bread. Other motivators were the constant political strife and the dream to return to Italy with enough money to buy land and improve their lives. Fully 80% of Italians were farmers and couldn't afford modern farming equipment to better their lives. Rural Italians lived in harsh conditions, residing in one-room houses with no plumbing or privacy. In addition, many peasants were isolated due to a lack of roads in Italy.  It was difficult to feed such a large family in rural Italy It was difficult to feed such a large family in rural Italy Most Italians didn't own land, so they were indebted to landlords, who charged high rents and took a portion of their crops. Higher wages in America--as often falsely advertised by many flyers produced by steamship companies--proved to be an attractive draw. AN Italian contadino who farmed year-round might earn 16-30 cents per day in Italy. A carpenter in Italy would receive 30 cents to $1.40 per day, making a 6-day week’s pay $1.80 to $8.40. In America, a carpenter who worked a 56-hour week would earn $18. Farmers faced even further reasons to immigrate. Besides falling wheat prices, fruit and wine prices were also falling. The phylloxera virus destroyed nearly every grape vine used to produce wine. America was envisioned as a place of opportunity, with abundant land, high wages, lower taxes--and at the time--no military draft. Yes, one more reason why many Italian men wanted to leave Italy... to escape conscription into the military. But still, many wanted only to go to America, earn money and return to buy their own land. Political hardship was also a factor in motivating immigration. Beginning in 1860, la Guerra dei Contadini del Sud (the Southern Peasants War) began. This was an uprising to resist the changes that the North was forcing on the Southern provinces with the Unification. Led by mostly brigands (many of who had previously had the support of contadini), this was a type of "social banditism" who were rebelling in order to retain their small sphere of power and wealth in their rural areas. The poor contadini were caught suddenly in the cross fire. Later in the 1870s, the government took measures to repress political views such as anarchy and socialism. Many Italians came to the United States to escape political policies and warring factions.  Taking a train to an Italian port city Taking a train to an Italian port city Italian immigrants to the United States from 1890 onward became a part of what is known as “New Immigration,” which is the third and largest wave of immigration from Europe and consisted of Slavs, Jews, and Italians. This “New Immigration” was a major change from the “Old Immigration” which consisted of Germans, Irish, British, and Scandinavians and occurred earlier in the 19th century. Between 1900 and 1915, 3 million Italians immigrated to America, which was the largest nationality of “new immigrants.” These immigrants, a mix of both artisans and peasants, came from all regions of Italy, but the largest numbers were from the mezzogiorno--Southern Italy. Between 1876 and 1930, out of the 5 million immigrants who came to the United States, fully 80% were from the South, representing such regions as Calabria, Campania, Abruzzi, Molise, Apulia and Sicily. The majority (2/3 of the immigrant population) were farm laborers or laborers, or contadini, as noted on the ship manifests when arriving at Ellis Island. The laborers were mostly agricultural and did not have much experience in industry such as mining and textiles. The laborers who did work in industry had come from textile factories in Piedmont and Tuscany and mines in Umbria and Sicily. Though the majority of Italian immigrants were laborers, a small population of craftsmen also immigrated to the United States. They comprised less than 20% of all Italian immigrants and enjoyed a higher status than that of the contadini. The majority of craftsmen were from the South and could read and write; they included carpenters, brick layers, masons, tailors, and barbers. The first wave of Italian immigration began in the 1860s after the Unification of Italy. By 1914, the number of Italians immigrating to the United States reached it's peak at over 280,000 making the journey to America. Since there was a larger population and higher skilled laborers (such as miners) in the industrial northern Italian provinces, a higher number emigrated from the North. But even though the South had a sparser population with less labor skills, more per capita came from these southern regions. In fact, by 1915, the number of emigrants from the South nearly matched those coming from the North.  Due to the large numbers of Italian immigrants, Italians became a vital component of the organized labor supply in America. They comprised a large segment of the following three labor forces: mining, textiles, and clothing manufacturing. In fact, Italians were the largest immigrant population to work in the mines. In 1910, 20,000 Italians were employed in mills in Massachusetts and Rhode Island. An interesting feature of Italian immigrants to the United States between 1901 and 1920 was the high percentage that returned to Italy after they had earned money in the United States. About 50% of Italians repatriated, which can be interpreted as many having trouble assimilating into the American way of life. Some of this can be blamed on the blatant racist views toward Italians and refusal to hire them for better paying jobs. In the large cities, tenements were essentially slums. If an immigrant couldn't get a decent living wage, they might reconsider trying to raise their family in America. Because Italian immigrants tended to be gregarious--often clustering together in "Little Italys", often they didn't feel there was a need to learn English, another factor in not being able to secure better paying jobs. Many might have fallen into the trap of getting housing or jobs through a padrone, a boss and middleman between the immigrants and American employers. The padrone was an immigrant from Italy who had been living in America for a while. He at first might seem helpful in providing lodging, functioning as safe "bankers" or money changers (often short changing), and found work for the immigrants (albeit, for a percentage of their earnings). Often, they would get the work that they could do in the apartments they rented to them... making silk flowers, rolling cigars, sewing, etc. After a few years of paying a percentage of their salaries to these padrone, many immigrants got discouraged enough to return to the homeland. At best, these situations became indentured servitude, at worst slavery. Child labor was also a product of these padrone, filling sweat shop factories with children as young as 10 years old. Prejudice Rears its Ugly Head Both immigrant contadini and those with skills faced economic as well as ethnic prejudices upon entering the labor force in America. The poor economy caused hostility toward Italians and many were labeled as strikebreakers and wage cutters from 1870 onward. American workers already feared the new mechanization in factories was the cause of taking away their jobs. Job bosses used Italians to fill their jobs as scabs during labor strikes. Prejudices were especially aimed at (as perceived) darker skinned Southern Italians who became scabs during strikes in construction, railroad, mining, long shoring, and industry. The Italian workers were called derogatory names such as:

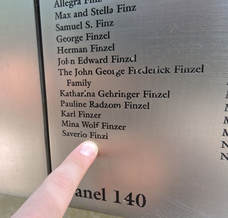

Italians were the only workers to work along side black people and employers preferred Slovaks and Poles to Italians. At the time, it was said that "railroad superintendents ranked Southern Italians last because of their small stature and lack of strength”. In the mining industry especially there was an ethnic hierarchy: English-speaking workers held the skilled and supervisory positions while the Italians were hired as laborers, loaders, and pick miners. It was not until the 1920s that Italians became more integrated into the American working class, regardless of whether or not they spoke English. More immigrants started to work at semi-skilled jobs in factories as well as skilled positions but one-third of the population remained unskilled. In trade unions, meetings were held in English and Italians were not elected to official positions.  Dad's name on the Ellis Island wall - Saverio Finzi Dad's name on the Ellis Island wall - Saverio Finzi My Grandfather, Sergio Finzi had made two preliminary Voyages across the Atlantic trying to establish connections and work so he could bring his wife and children over. He was a tailor, a skill he brought with him from Molfetta. They were poor. My father told of not having enough coal or wood to fire up their kitchen stove--the only heat in winter. He said he and his brother walked the railroad tracks to pick up scraps of coal fallen from passing trains. They left school in the fourth grade to help the his familia scrape a living from their new home. Many Italian immigrants suffered--and endured. We are all proof if this fact. Italian immigrants--as many immigrants from other lands--help build this country. They helped defend it. They assimilated. They became citizens. Paid taxes. Sent their kids to school. And here we are... over 100 years later and many in our country are still ambivalent or even dead against immigrants. Have we really lost sight of the fact that unless we have 100% Native American blood running through our veins, that we all are descended from immigrants? Starting in 1888, photographer Jacob Riis, a Danish immigrant, in an attempt to call attention to the suffering of immigrants, photographed the Manhattan tenement slums where Italian (and other) immigrants were living in squalor. He was followed by Lewis Hines, who photographed not only the immigrants and slums but the children who were the most helpless victims of this inflicted poverty. Enjoy the slide show... and try to remember the hardships our fore-bearers went through to get us where we are today... --Jerry Finzi At the beginning of 2017, we've started re-construction and re-organization of Grand Voyage Italy's pages. If you don't find what you are looking for on this new History page, use the Search Box to find what you need. Grazie!

|

On Amazon:

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed