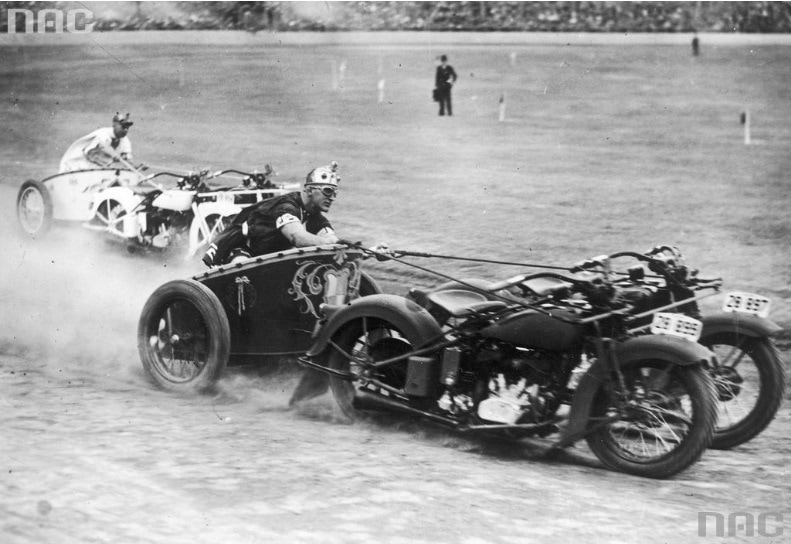

"Engines" were small at first - a Half-Horsepower (Donkey) powered cart "Engines" were small at first - a Half-Horsepower (Donkey) powered cart No one really knows when chariot racing started, but the Greeks had chariot races during the first millennium BC and made the races part of the Ancient Olympics in 680 BC. Of course, chariots themselves were in use 4000 years ago. The most important development was a wheel with spokes. Before spokes, wheels were made from solid slabs of wood or thick shaped planks--both added weight before the cargo was even placed into the cart. Carts being pulled by animals--mostly oxen--were in use as early as 6000 years ago... but having an oxen as your main engine was very low torque--like a Mac truck. "Engines" improved slowly... at first a donkey or even a goat... sort of like early Model-T Ford runabouts. Then higher horsepower came in the form of mules and horses, one horsepower to start. The first chariots were used as delivery and work vehicles.  This car just wasn't fast enough to avoid the Law This car just wasn't fast enough to avoid the Law The history of NASCAR racing started with delivery vehicles, too. During the period of Prohibition in the 1920s, a bunch of backwoods good ol' boys smuggled liquor in from Canada or bootlegged whiskey (moonshine) from the tobacco fields of Georgia through to Chicago, New York and other big cities. Especially in the deep South, illegal booze was transported with with stock cars... they needed to look like every other car so as not to attract much attention. But special equipment was needed for the task at hand: heavy shocks and springs were added for the weighty loads of filled bottles and jars, and for smoothing the ride when driving fast on bumpy, unpaved roads; a high-powered engine was needed to deliver their booty quickly and to leave chasing authorities in the dust. High performance stock cars were born when Federal agents took chase... You can imagine that chariots started out also as "stock" units, with additions and modifications needed to accomplish their task. Adding a horse in place of a goat (more horsepower--literally) meant goods could make it to market faster and beat the competition. Perhaps this is where chariot racing started... two lemon growers meeting on the road and trying to beat each other to market. I'm certain that Greek and Roman officials taxed wine heavily, giving the ancient wine producer reason to race their "special" supply of wines past tax collectors to their regular clientele. Up until the 1st century AD, chariots were also used in the military. Racing to overcome the enemy, or perhaps betting on who would get to the battlefield first, might have also planted the seed of chariot racing. Special performance equipment on chariots continued to advance. In Ancient Rome, a two horse chariot was called a biga, a three horse chariot was a triga, and a supercharged, four horse power chariot was called a quadriga. Hey, they all sound like great names for modern car models! Vroom, Vroom! The horse chariot was a fast and lightweight vehicle and was indeed Spartan inside... again, like a NASCAR vehicle. There was barely a floorboard, no windows, and a waist-high guard at the front and sides. It must have been as uncomfortable a ride as what NASCAR race drivers have to put up with. Unlike other Olympic events, charioteers in Greek races did not perform their sport in the nude. Like NASCAR drivers, they wore safety gear: The clothing was itself their safety gear... a sleeved garment called a xystis went down to the ankles and had a belt fastened at the waist. Two criss-crossed straps across the back prevented the xystis from filling up with air during the race. Roman charioteers wore more protective gear--perhaps because most were not slaves, but paid professionals. They word helmets, leg guards, body armor or chain mail and wrapped the reins around their forearms. In case of a crash they would be dragged along the ground and could be killed, so one final bit of protection was to carry a falx (a curved knife), used to cut their reins away in an emergency. When official chariot racing became popular, it wasn't the driver who owned the horses and chariot. Just as in NASCAR, there were team owners. In 416 BC, the Athenian general Alcibiades had seven chariots in the race, and came in first, second, and fourth. He obviously hired drivers to be at the wheel... er... at the reigns, that is. Unlike NASCAR drivers who some might argue are slaves to their sponsors, many drivers (who remain unknown to this day) were actual slaves. The racetrack--called a Hippodrome (Greek) or a Circus (Roman)--was oval with tight turns on either end, just like (getting tired of saying this) NASCAR courses. Chariots went around and around, counterclockwise, with nothing but left turns (sound familiar?) These turns were deadly and many crashes occurred. Although running into an opponent with the intent to cause a crash was strictly forbidden--it was tolerated because it made the crowds go wild. The ancient Greek and Roman spectators loved crashes, as they loved any blood sports of the day. Modern NASCAR spectators are conflicted--as loyal fans, they don't want to see their favorite drivers injured or killed, but just as the ancient spectators, when a crash happens, they get an adrenaline rush and a thrill they'll remember for a lifetime. Chariot races began with a procession into the hippodrome, while a herald announced the names of the drivers and owners--he had to be a very loud public speaker, indeed. NASCAR tracks have lots of loudspeakers. On the flip side, aside from cheering crowds and the sound of horses hooves on a dirt track and the occasional cracking of wood during a crash, a chariot race must have been a quiet affair when compared to the off-the-scale high decibel assault the NASCAR fan must endure as car after car go revving by for hours on end at up to 200 miles per hour! The smells were very different too... horse poop versus the exhaust from 110 octane fuel and burning rubber...  Ready to throw down the "Mappa" for the race to start Ready to throw down the "Mappa" for the race to start A race called the tethrippon (in Greek regions) had twelve laps around the track, while Roman races often had 7 laps to allow more races in a single day for betting--Romans and gambling went together more than in the Greek culture. Even more interesting is the way the races were started. In the same way that NASCAR uses a pace car to get cars up to starting speed before checkered flag starts the race, the Ancients used mechanical devices to accomplish a similar task for a rolling--or rather--galloping start. The starting gates were lowered and staggered in a way so the chariots on the outside lanes began the race earlier than those on the inside. The race only began when each chariot was lined up next to each other--"keeping pace". Chariots in the outside lanes would be moving faster than the ones on the inner lanes. While flags are used in modern auto racing, mechanical devices shaped like eagles and dolphins were raised to start the race. Dolphins were lowered with each successive lap. In Rome, often the Emperor himself would start the race by dropping a white cloth called a mappa. In the end, the winners were given their awards right away. An olive wreath was placed on their head. In the Roman Empire there would be cash awards or possibly a gift of a slave for the charioteer. Fame was also part of the game, as is the case today. Scorpus, a celebrated driver won over 2000 races before being killed in a collision at the ripe age of 27. Most charioteers had a short life expectancy. The most famous driver was Gaius Appuleius Diocles who won 1,462 out of 4,257 races. When Diocles retired at the age of 42 (after 24 years) his career winnings 35,863,120 sesterces--approximately 15 billion dollars today--making him the highest paid sports star in human history. A couple of more interesting differences: Women weren't permitted at the races as they are today; and while today's largest NASCAR racetracks hold under 150,000 spectators, the Circus Maximus in Rome held 250,000! Gentlemen, start your... er... feed your horses! Go! --Jerry Finzi Copyright 2017, Jerry Finzi/Grand Voyage Italy - All Rights Reserved

Names can tell a lot when researching our Italian roots. But there are some names which tell a sadder tale back several generations or so. Orphans and foundlings in Italy were given special names. This list includes the most common surnames used.

Some means of names are pretty obvious: Bastardo... for bastard. Della Femina for From a Woman. Dell'Amore means From Love. All are a testament to those who came before and the trials they must have gone through to get through troubled times of war or poverty or disgrace. Many suffered through the horrors of war or famine. Anyone bearing these Italian surnames should be proud of what their fore-bearers went through to give life to their children and their children's children. Although these names do have a high probability of being rooted in an ancestor being orphaned, there are exceptions to this. Amodio (Love God), Arfanetti (Orphan), Armandonada (Donated by Hand) Bardotti (The sterile hybrid offspring of a male horse and a female donkey) Bastardo (Bastard), Circoncisi (Circumcised) Colombini (Little Dove), Dati (from you) Circoncisi (Circumcised) De Alteriis (Changling), De Angelis (From Angels) Della Donna (From a Lady), Della Femmina (from a Female) De Domo Magna ("Of the Ospizio" ,of the Hospital or Hospice) Degli Esposti (Abandoned) Della Scala (Name assigned by foundling home in Sienna) Della Fortuna (from Luck), Della Gioia (From Joy), Della Stella (From a Star) Della Casagrande (of the Hospital/Orphanage) Dell 'Amore (from Love), Dell'Orfano (the Orphan) Del Gaudio (of Grace & Goodness), Diodata (God Diven) D'Amore (Love), D'Ignoto (from Unknown), Diotallevi (God Raised You) Esposto, Esposito, Esposuto (Lost) Fortuna (Luck), Ignotis (Unknown), Incerto (Uncertain) Incognito (Unknown) Innocenti, Innocentini (The Lost Ones) Mulo (Mule), Naturale (Natural/Careless) Nocenti, Nocentini (Little Innocent), Ospizio (Foundling Home) Palma (when child is abandoned on Palm Sunday) Proietti (Thrown away - also, Projetti, Projetto, assigned by an ospizio in Rome) Ritrovato (Discovered) Sposito (Lost), Spurio (Illegitimate) Stellato (The Stars), Trovatello, Trovato (Foundling) Ventura, Venturini (Angels, Little Angels) Legislation passed in 1928 outlawed the practice of assigning orphans surnames indicating their illegitimacy or abandonment, but surnames of some sort still had to be given to these children. These were sometimes the surnames of royal and noble families, but more often they were geographical in nature or alluded to the day, month or season of the child's birth (i.e. Sabato, Maggio, Primavera and so forth). --Jerry Finzi |

On Amazon:

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed