|

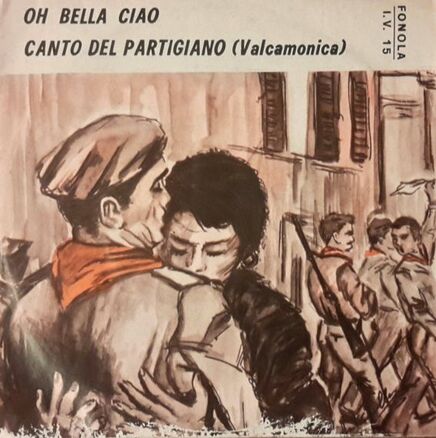

E questo è il fiore del partigiano … morto per la libertà! This is the flower of the partisan … who died for freedom April 25, the Festa della Liberazione is an Italian national holiday that commemorates the liberation from fascist domination in Italy. On this day you might hear the partisan song, Bella Ciao on the radio, in parades, or sung by small groups in small town piazzi all over Italy. It is the song of I Partigiani, men and women who fought against the Nazis and Fascists primarily in Northern Italy from 1943 to 1945. This is the period called La Resistenza, the Resistance. The song is set to the melody of a traditional folk song and became the anthem of the Italian resistance movement during World War II, sung by the anti-fascist rebels who fought against the atrocities of the Nazis and Benito Mussolini. The lyrics are symbolic of the sacrifices made for freedom. Each April 25 there are Liberation Day festivities throughout the country, paying tribute to those who lost their lives in in the fight to free their country.  Mussolini, the second from the left Mussolini, the second from the left In 1943, Mussolini was deposed by the King Victor Emmanuel III of Savoy. The new government signed an armistice with the allied forces, while Mussolini was helped by the Nazis, fleeing to Northern Italy where he created a puppet state. After liberating Southern and Central Italy, the Americans passed through the Apennines. Partisans became an effective fighting force against the Nazis and Fascists in the mountain towns. On April 25th, 1945 Northern Italy was at last liberated. Mussolini would be executed by Partisans after a quick, public trial near Milano within 4 days. Shot along with his mistress, Claretta Petacci, and his other henchmen, their bodies were at first laid out in Piazzale Loreto where huge crowds of Italians took turns throwing trash on them, kicking and worse. Afterwards, their bodies were hung upside-down on the rafters of the local gas station. Perhaps a fitting end to one of the monsters of modern history. However, instead of burning the body of Mussolini (as perhaps should have been done) his body was first buried, then stolen, and afterwards found and hidden secretely in a monastary for eleven years. Unfortunately (for the Italy and the World), in May 1957 the newly appointed Prime Minister, Adone Zoli, agreed to Mussolini's interment at his place of birth in Predappio in Romagna. This was for obvious political reasons since Zoli was reliant on the far right to support him in Parliament. Sadly, even today, the remains of Mussolini has become a pro-fascist shrine or sorts. For this reason, it's a very good thing that the Russians "lost" the body of Hitler. Since the Liberation, Italy has been free from dictators, although the current neo-fascist movements are a signal to never forget what history has taught us... --Jerry Finzi Copyright 2019, Jerry Finzi/GrandVoyageItaly.com - All Rights Reserved Not to be published without expressed permission.

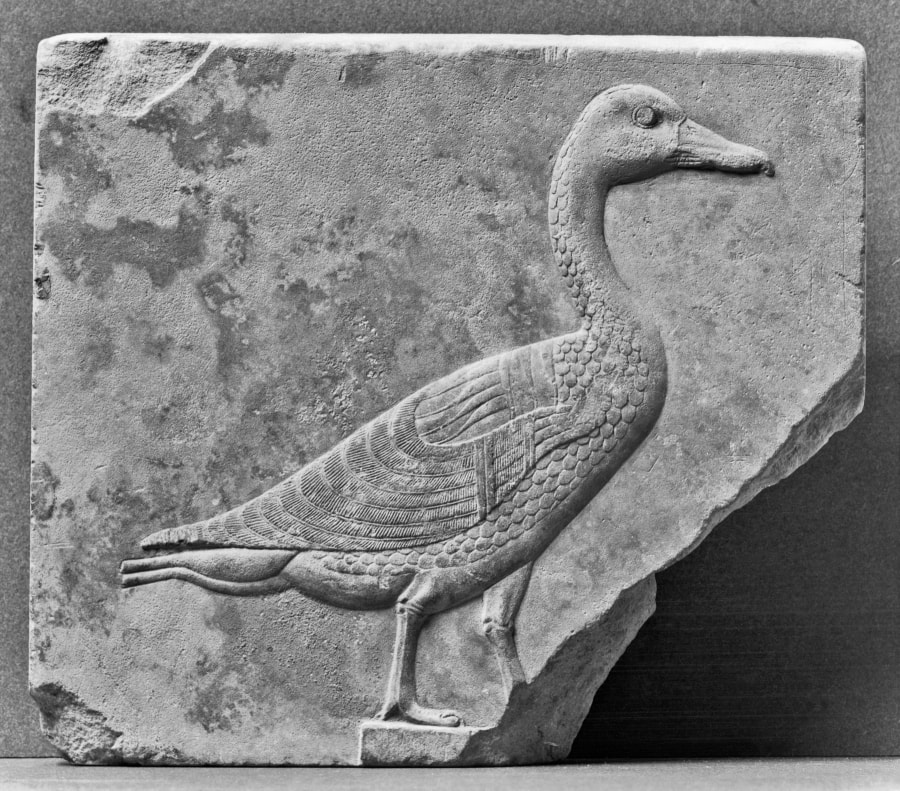

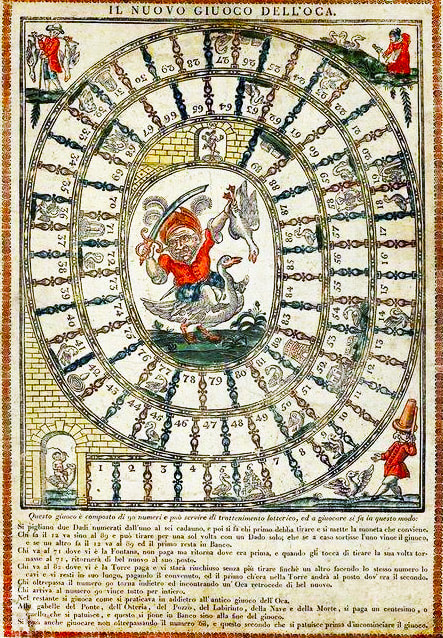

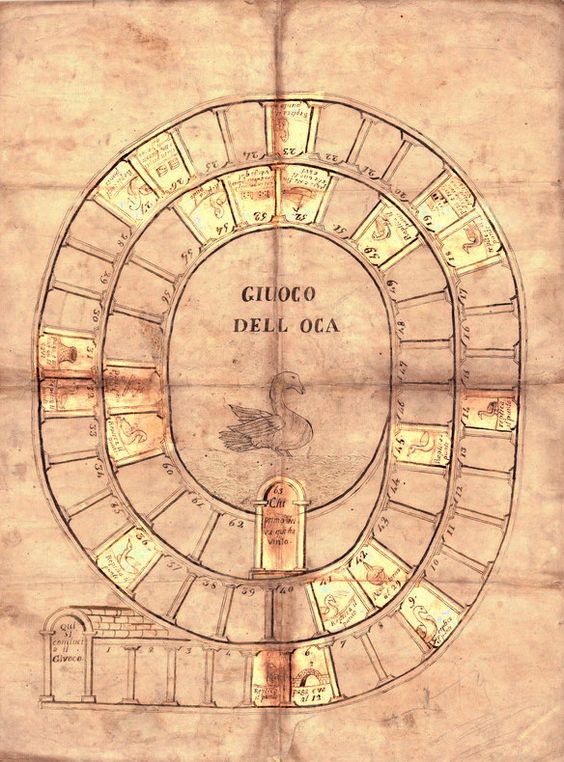

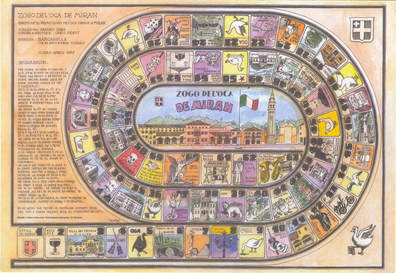

Boy wrestling a goose Boy wrestling a goose Domestication of geese dates back to Neolithic times, about 6,000 years ago. During the Roman Empire there is much evidence of breeding geese in both writings and art. Of course, the ancient Romans saw the goose as a ready source of food high in protein and fats. L'oca (the goose) was written about in the 1st century collection of recipes by Marco Gavio Apicius, the most famous of Roman culinary maestros. The goose was fattened with dried figs and wine mixed with honey, then were either oven roasted, spit-roasted or boiled and served with a sauce made with pepper, coriander, mint, rue and olive oil. Its liver was a delicacy to be dipped in milk and honey. It's also obvious to historians that Charlemagne, the Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire also favored the development the valuable goose. In the Middle Ages he personally owned 30 geese on his farm for domestic use and trade. In Italy as well as other countries, goose is the preferred celebratory food on the day of San Martino. Aside from food, the goose served many other purposes. In the 15th century, Paolo Santonino wrote in his Itinerarium Sanctonini, "Wherever there is an abundance of geese, even the poorest peasants have a feather bed". With their exceptional eyesight, wide field of vision, extremely loud and boisterous honking, a gaggle of geese makes excellent guards to warn of poachers, intruders, thieves and predators, and unlike dogs, they can't be silenced by offering them a treat.  Protecting the brew as it ages Protecting the brew as it ages In 390 BC, when Rome was attacked by Gallic troops, their honking alarmed when an enemy attempted an attack. Even today, geese are used in Italy, not only to eat pests in vineyards and olive and nut groves (a very organic approach to avoid pesticides), but they will warn the owner of poachers entering their lands. They have also been used to protect wine and whisky cellars. Old school Italians even forecast the weather using the goose... at the dinner table, that is. If the bones are white, the winter will be short and mild; if they are dark is a sign of rain, snow and cold. Gaming the Goose  The goose has also given its share of fun to early households in the form of the game called Gioco dell'Oco. Even saying the name is fun... Jy-Oko, dell Oko. In the Game of the Goose the object is fairly straightforward, rolling the dice and being the first to make it to the center. There are obstacles to avoid, just like in the child's game Candy Land, except rather than getting stuck on a Licorice Stick, the obstacles are the Inn, the Bridge and Death. The game originated sometime in the 16th century, and is considered the forefather of most board racing games. Manufactured versions appeared in the late 19th century, and modern versions are still played throughout Italy and Europe. There are even life-sized games with real geese played during the Festival of San Marino in some towns like Mirano and Mortara.  Mirano festival Mirano festival In Italy, goose-based lunches are typical northern regions such as Friuli, Veneto, Lombardy and Romagna. In several places the Dinner of San Martino is an entire menu based on goose. In the province of Pavia the town of Mortara has the nickname City of the Goose where one specialty is goose salami, called Salumi dell'Oca. Having a strong Jewish heritage, this high fat sausage replaces typical pork sausage on the table and is prepared in the Kosher tradition. In addition to their fatty meat, geese produce large edible eggs, weighing up to 6 ounces each. They are used just as chicken eggs are, but have a much larger yolk with a more gamey flavor. As part of the Cucina Povera in past history, a goose egg would have been preferred over a chicken egg since each egg contains much more fat and calories (essential to get through a lean growing season or winter). Perhaps this is where the idea of the Goose Who Laid a Golden Egg came from. Here's a comparison between chicken and goose eggs: Chicken - 1.5 oz; 72 calories; 4.75 grams total fat/1.56 grams saturated;6 grams protein Goose - 6 oz; 266 calories; 19.11 grams total fat/5.1 grams saturated; 20 grams protein In a modern healthy diet, one rarely considers eating goose eggs, especially if trying to lower their dietary cholesterol... One large chicken egg contains 186 mg of cholesterol, but a single goose egg contains 1,227 mg of cholesterol! So you see, the contadini (farmers) of Old Italy considered raising geese as a sound investment. They are a good source of high fat, high calorie, high protein food; a "watchdog" against intruders; down for his beds, and for the most part, geese get their own food, grazing for garden pests and are happy to eat kitchen scraps. Keeping geese around was very furbo.  Prosciutto dell'Oca locked in its stand ready for thin slicing Prosciutto dell'Oca locked in its stand ready for thin slicing In northern Italy, where there is a large Jewish culture, there is an artisan process of creating Prosciutto dell'Oca (goose ham). This is a lean product, similar to prosciutto, made using the leg of the goose, seasoned with salt, pepper and spices and aged for about 2 months or more. Its color is dark red, with a sweet taste and an intense aroma. It is used as an appetizer for important occasions and often served on bruschetta with a glass of local wine. The city of Mortara, offers Prosciutto dell'Oca during both spring and fall festivals. Siena and its Winning Contrada dell'Oca  In Italy, cities are divided into contrade (districts or wards), with the most famous being the 17 contrade of Siena whose representatives race on horseback in the Palio di Siena, run twice each year. Each contrada has an animal as its mascot, produly and loveingly displayed on flags all over the city. The one that we point out here is the Contrada dell'Oca. If you love geese, than this is the flag you should be rooting for when you visit Siena to witness this exciting horse race. But there's another reason... The Noble Contrada dell’Oca holds the record of winning 65 Palios races, from its inception in 1644 to the present day.

Viva l'oca! --Jerry Finzi

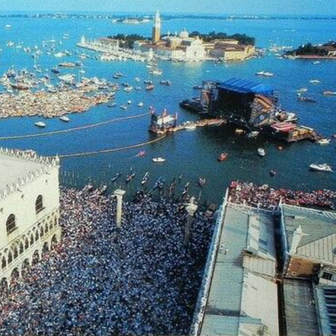

When they arrived in Venice in 1989, Pink Floyd were met by over 200,000 Italian fans, but also by a large contingent of Venetians who had no desire to see the show happen at all. The city’s municipal administrators viewed the concert as an assault against classical Venice. The concert was also stepping on traditional toes considering it was scheduled to take place in St. Mark’s square, coinciding with the hugely popular Redentore festival (the Feast of the Redeemer with fireworks from a nearby island). With Venice already threatened by sinking foundations, winter flooding, and with the memory of the St. Mark's bell tower having collapsed in 1902 (and having been rebuilt) many were concerned about the safety of the fragile historic art and architecture of the city.

Three days before the concert's July 15th date, Venice's superintendent for cultural heritage vetoed the concert, claiming that the amplified sound would damage the mosaics of St. Mark’s Basilica, while the whole piazza could very well sink under the weight of so many people dancing in unison.

The ban made concessions to allow the concert to go forward: lowering the decibel levels from 100 to 60 and performing from a floating stage 200 meters from the piazza. The concert was broadcast on TV in over 20 countries with an estimated audience of almost 100 million. The concert drew 150 thousand more people than actually lived in Venice, and even though fans were on their best behavior, one group of statues sustained minor damage and the crowds left behind 300 tons of garbage and 500 cubic meters of empty cans and bottles. And due to the fact that public porta-potties were not provided by the city, fans relieved themselves on the monuments and walls.

The concert placed tension between different political factions forcing the Mayor to resign with shouts of “resign, resign, you’ve turned Venice into a toilet.” His comrades on the city council also stepped down. The band may have taken down the city’s government, but they put on a hell of a show--one the Italian fans, and the millions of who watched from home, will never forget.

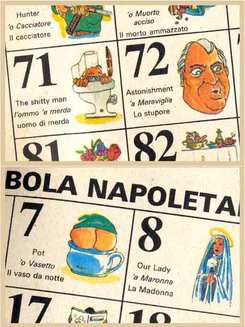

On our modern Julian calendar, March is the third month of the year, but to ancient Romans, Martius (as it was called) was the first month of each new year. It makes sense when you think about it. Right now in Italy, the flowers are blooming all over the place. Things are growing, the weather is warm again and it makes sense to think of Spring as the beginning--the birth--of a new year. The Romans celebrated holidays from the first through the Ides of March (on the 15th) to bring in their New Year. The most important celebration on the Ides was to the god Jupiter, the supreme deity, but also to Anna Perenna, the goddess of the year itself. Anna Perenna was more popular with the plebeians of Rome who drank, played games and had picnics. Later, in Imperial Rome, the Ides began a week long celebration for several various festivals. The so called "Ides" of a given month refer to the midpoint of a month, for some months (like March) falling on the 16th, and on others falling on the 13th day--all governed by the phases of the moon. The Ides on the ancient Roman calendar was on the new year's first new moon. The Romans didn't use day numbers, but counted backwards from given points in the month... the Nones (5th or 7th, depending on the length of the month), the Ides (13th or 15th), and the Kalends (1st of the following month). Of course, we all know that in modern times, the Ides of March is the day that Julius Caesar was assassinated in 44 BC. Shakespeare tells the tale in his classical play Julius Caesar... Caesar was stabbed to death by a crowd of his opponents, with Brutus and Cassius at the lead. A seer foretold that Caesar would come to an end on the Ides, but when the day came he saw the seer on the street and laughed in his face, saying that nothing bad had happened, but the seer answered back, "...Yet".  Recently, researchers think they have found the exact location of where Julius was stabbed 23 times by the group of senators... at the Largo di Torre Argentina, in the center of Rome not far from the Pantheon, known nowadays to tourists and Romans alike for the tram station adjacent to the site and all the feral cats that live among the ruins. Ancient texts always claimed that Caesar was killed in the Curia of Pompey, a theater at the site, but until recently no archeological evidence could be found. In 2012 a large concrete marker was found which was erected as a monument to Caesar by his loyal followers after his death... All those cats seem to be wandering and waiting for Caesars return... You can hear their call... "miao, miao... miao..." Oh, I almost forgot... Felix Annus Novus! (That's Happy New Year in Latin.) --Jerry Finzi You can also follow Grand Voyage Italy on: Google+ StumbleUpon Tumblr  Playing Tombola during the Christmas and New Year holidays Playing Tombola during the Christmas and New Year holidays Tombola (or tombala) is a game that is very similar to bingo in the States where numbers are picked from a drum and called out, and players have to cover an entire row to win. It is played pretty much all over Italy from Christmas Eve to the Epihany while the little ones are waiting for La Bufana (the Good Christmas Witch) to come with their presents. Although more modern Tombola sets come with chips or blots to cover the numbers, most people play the traditional way--covering the numbers with torn pieces of orange or tangerine skins or beans or lentils.  Detail of Tombola cards... both naughty and nice Detail of Tombola cards... both naughty and nice The boards are similar to bingo boards, but in Naples the boards are very different. Numbers range from 1 through 90, but the interesting thing is, each number on the board also contains a picture, usually with the name in Italian, Neapolitan dialect and some even have an English translation. Tombola's roots lie in a fortune telling game that was used hundreds of years ago to predict the future or help understand the meaning of dreams. Each number is represented by a symbol or picture with a particular meaning. The really strange thing is--at least to us Americans--is that many of the pictures are downright rude or sexual. Even stranger is the fact that a religious picture might be right alongside a very naughty one!  A Tombola poster A Tombola poster Played casually in the home, people may play for small change or Euro coins, but they may also play just for fun... and offer toys, cookies or other dolci as prizes, usually letting the children win. When they do play for money, things can get pretty heated and loud. After all, these are Neapolitans, after all. The peel their oranges, eat the oranges, place pieces of peels on the numbers and laugh and talk for hours on end. It's all in fun and a great way to start the Holiday season on Christmas Eve, or to finish it off when playing on New Year's Eve. There are even television shows that play the game and offer prizes. If you feel like giving Tombola a try during the holiday season, or any other time of the year, here is an "automatic" Trombola game (on Amazon, $31).

--Jerry Finzi At the beginning of 2017, we've started re-construction and re-organization of Grand Voyage Italy's pages. If you don't find what you are looking for on this new History page, use the Search Box to find what you need. Grazie!

|

On Amazon:

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed