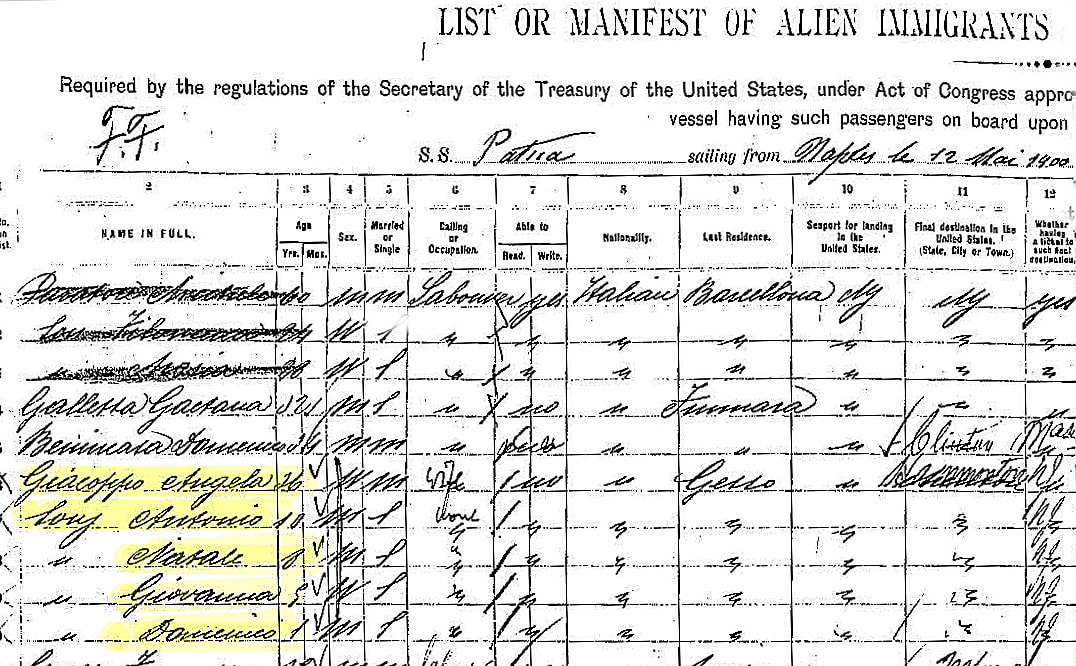

Jill Biden might not be a full blooded Italian descendant, but there are many Italian-Americans who are only half Italian yet still identify themselves as "Italian" when asked. For instance, I'm a first generation Italian-American with both of my parents being Italian, but my wife has an Italian father and Polish mother. The interesting thing is, she has never really identified as Polish-American since most of her cultural influences growing up were from the Italian side of her family. Even late night TV host Jimmy Kimmel (originally Kummel, from his German paternal grandfather), thinks of himself as Italian-American, since the great family influences were from the Neapolitan side of his mother's family. There has been recent talk of Jill Biden having Italian roots, but I wonder how she identifies herself when asked about her heritage. I'm certain, for politically correct reasons, her answer to journalists would be, "I'm American". Still, in my experience, having even a tiny bit of Italian blood running through someone's veins is enough for anyone to proudly embrace their Italian roots. Who wouldn't want to be Italian? Jill Tracy Jacobs Biden is half Italian. Her grandfather, Domenico Giacoppo emigrated from the small Sicilian village of Gesso, escaping the poverty and chaos created by recent earthquakes in the region of Messina. He later changed his name, in an attempt to Americanize it, to Jacobs. Jill's father, Donald Carl Jacobs (1927–1999), was a U.S. Navy signalman during World War II, who afterwards used the G.I. Bill to attend business school, eventually becoming head of a savings and loan institution in Philadelphia. Her mother, Bonny Jean Godfrey Jacobs (1930–2008), was homemaker of English and Scottish descent. One of Biden's distant Sicilian cousins, Caterina Giacoppo offered an invitation that has gotten a lot of press lately... “Jill, I’m here, my house is open for you, as is our entire Sicilian village of Gesso where your grandfather came from. Please do come visit us next time you travel to Italy.” Gesso is a tiny, close-knit community with only 600 inhabitants in the province of Messina. She went on, "I would be very happy if Jill came here ... I would like to meet her. We are ready to have a nice party all over the commune. If you come, I'll cook you baked pasta, roasted braciolettine arrostite and other local delicacies such as eggplant parmigiana, pasta alla 'ncasciata and cannoli filled with fresh goat ricotta, which is one of my specialties" Flavors of Gesso, Sicily Pasta alla 'Ncasciata is the local, Messinese version of baked pasta with eggplant and caciocavallo cheese. Braciolettine Arrostite is from the Arabo-Sicula cuisine, a mix of Arab and Sicilian flavors. Similar to beef brasciole, it's charcoal grilled with a stuffing of currants, pine nuts and pecorino cheese. Will we be seeing pasta and pizza nights at the White House soon? Only time will tell, but as far as we're concerned, Joe Biden is more than just an Irish-Catholic... he's Italian by sheer association! The evidence is clear since his go-to menu for many past fund-raising dinners includes a caprese salad, angel hair pasta pomodoro, raspberry sorbet, and biscotti. Good luck to them both! --Jerry Finzi List of September 11 Victims of Italian Heritage

Never Forget... --GVI By Gianni Pezzano

The decision to migrate is never easy but, no matter how hard the decision, at the moment of departure we never understand the true price paid by those who leave a country for a new life. It will then be the cruelty of time that will uncover the true pain caused by long distances and the ones who feel it are not only the migrants, but also the children and descendants. From telegrams to messages When I woke up Saturday morning there was a message on my mobile phone that I had feared since the first day in Italy. My uncle Rocco had passed away, the last of my father’s eight brothers and sisters and with him an entire generation of the paternal side of my family ended. It will not be the last such message and they never become because less painful, in fact… After the first moment of sadness, which has grown since then, I remembered my mother’s scream that evening fifty years ago when the telegram arrived to tell us of the death of Nonno (grandfather). The change of technology has done nothing to reduce the pain. That was my first true experience of the migrant’s pain. Two years before my maternal grandparents had come to Australia to meet the new in-laws and above all the grandchildren that they knew only from a few brief words in the rare telephone calls and the photos sent during the long exchange of letters between my mother and Nonna (grandmother). Sadly I never met my paternal grandparents. Nonno had died before my parents’ wedding and I was too young to remember when Nonna followed a few years later. Read the entire article HERE (in both Italian and English)... The shameful treatment of Italian Immigrants during WWII show America’s propensity for xenophobic hysteria Their movements were restricted, their homes raided; in some cases, they were interned The men in suits were at the Maiorana family’s Monterey, California, home again. Mike, the family’s young son, watched as the agents rummaged through their belongings in search of guns, cameras, and shortwave radios. And again, they found nothing. This was during World War II, and the FBI had declared Mike’s mother an “enemy alien.” The sole source of evidence for this allegation was that she was Italian.

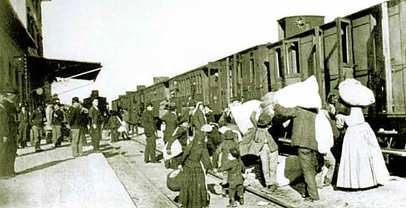

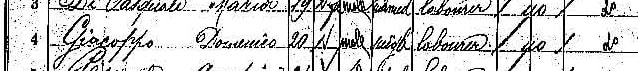

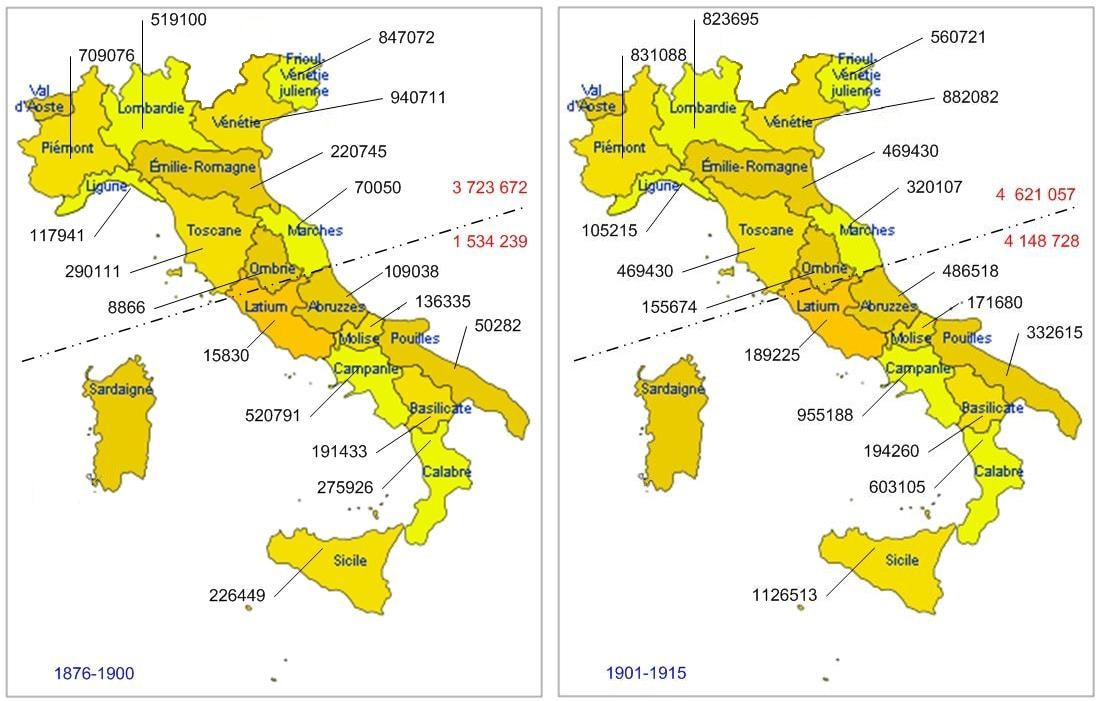

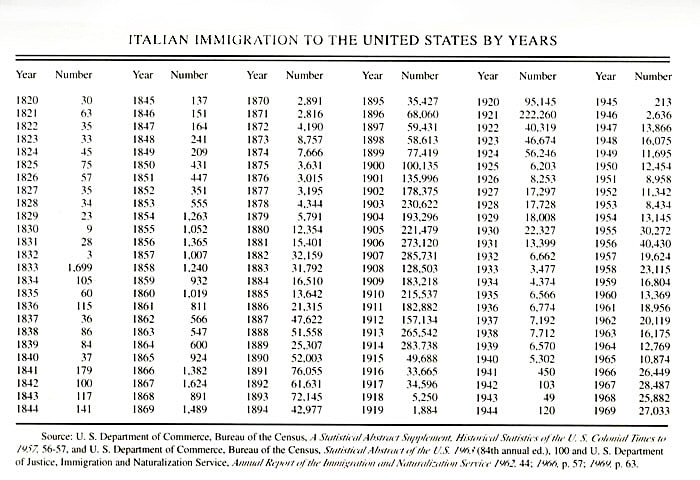

Elsewhere in California, an Italian poet’s work was scrutinized for treachery, and a father was hauled off by the FBI, leaving his wife and ten children without a breadwinner for four months. In New York, an Italian opera singer was thrown in prison without charge and just as unceremoniously released. Hundreds of Italian mariners who had been stranded in U.S. waters by the start of the war were loaded into Army trucks and hauled to an internment camp in Missoula, Montana, where some would remain for years. It was a distinctly American story, revealing the immigration system’s xenophobic through line. Poverty-stricken immigrants who were hated one day were approved of the next, only to be replaced by another allegedly dangerous immigrant group, all under the guise of national security. As beloved as Italian cuisine, sports cars, and fashion are on our shores today, things were different during the first half of the 20th century, especially during WWII.... CLICK HERE TO READ MORE...  Packed like sardines... Coming to America Packed like sardines... Coming to America The Many Reasons for Coming to America Poverty was the main motivation for an Italian leaving his family and home and putting up with the hardships of traveling to America. In 1898, widespread "bread riots" plagued all of Italy, with people protesting the lack of jobs and the sudden increase in the price of wheat and bread. Other motivators were the constant political strife and the dream to return to Italy with enough money to buy land and improve their lives. Fully 80% of Italians were farmers and couldn't afford modern farming equipment to better their lives. Rural Italians lived in harsh conditions, residing in one-room houses with no plumbing or privacy. In addition, many peasants were isolated due to a lack of roads in Italy.  It was difficult to feed such a large family in rural Italy It was difficult to feed such a large family in rural Italy Most Italians didn't own land, so they were indebted to landlords, who charged high rents and took a portion of their crops. Higher wages in America--as often falsely advertised by many flyers produced by steamship companies--proved to be an attractive draw. AN Italian contadino who farmed year-round might earn 16-30 cents per day in Italy. A carpenter in Italy would receive 30 cents to $1.40 per day, making a 6-day week’s pay $1.80 to $8.40. In America, a carpenter who worked a 56-hour week would earn $18. Farmers faced even further reasons to immigrate. Besides falling wheat prices, fruit and wine prices were also falling. The phylloxera virus destroyed nearly every grape vine used to produce wine. America was envisioned as a place of opportunity, with abundant land, high wages, lower taxes--and at the time--no military draft. Yes, one more reason why many Italian men wanted to leave Italy... to escape conscription into the military. But still, many wanted only to go to America, earn money and return to buy their own land. Political hardship was also a factor in motivating immigration. Beginning in 1860, la Guerra dei Contadini del Sud (the Southern Peasants War) began. This was an uprising to resist the changes that the North was forcing on the Southern provinces with the Unification. Led by mostly brigands (many of who had previously had the support of contadini), this was a type of "social banditism" who were rebelling in order to retain their small sphere of power and wealth in their rural areas. The poor contadini were caught suddenly in the cross fire. Later in the 1870s, the government took measures to repress political views such as anarchy and socialism. Many Italians came to the United States to escape political policies and warring factions.  Taking a train to an Italian port city Taking a train to an Italian port city Italian immigrants to the United States from 1890 onward became a part of what is known as “New Immigration,” which is the third and largest wave of immigration from Europe and consisted of Slavs, Jews, and Italians. This “New Immigration” was a major change from the “Old Immigration” which consisted of Germans, Irish, British, and Scandinavians and occurred earlier in the 19th century. Between 1900 and 1915, 3 million Italians immigrated to America, which was the largest nationality of “new immigrants.” These immigrants, a mix of both artisans and peasants, came from all regions of Italy, but the largest numbers were from the mezzogiorno--Southern Italy. Between 1876 and 1930, out of the 5 million immigrants who came to the United States, fully 80% were from the South, representing such regions as Calabria, Campania, Abruzzi, Molise, Apulia and Sicily. The majority (2/3 of the immigrant population) were farm laborers or laborers, or contadini, as noted on the ship manifests when arriving at Ellis Island. The laborers were mostly agricultural and did not have much experience in industry such as mining and textiles. The laborers who did work in industry had come from textile factories in Piedmont and Tuscany and mines in Umbria and Sicily. Though the majority of Italian immigrants were laborers, a small population of craftsmen also immigrated to the United States. They comprised less than 20% of all Italian immigrants and enjoyed a higher status than that of the contadini. The majority of craftsmen were from the South and could read and write; they included carpenters, brick layers, masons, tailors, and barbers. The first wave of Italian immigration began in the 1860s after the Unification of Italy. By 1914, the number of Italians immigrating to the United States reached it's peak at over 280,000 making the journey to America. Since there was a larger population and higher skilled laborers (such as miners) in the industrial northern Italian provinces, a higher number emigrated from the North. But even though the South had a sparser population with less labor skills, more per capita came from these southern regions. In fact, by 1915, the number of emigrants from the South nearly matched those coming from the North.  Due to the large numbers of Italian immigrants, Italians became a vital component of the organized labor supply in America. They comprised a large segment of the following three labor forces: mining, textiles, and clothing manufacturing. In fact, Italians were the largest immigrant population to work in the mines. In 1910, 20,000 Italians were employed in mills in Massachusetts and Rhode Island. An interesting feature of Italian immigrants to the United States between 1901 and 1920 was the high percentage that returned to Italy after they had earned money in the United States. About 50% of Italians repatriated, which can be interpreted as many having trouble assimilating into the American way of life. Some of this can be blamed on the blatant racist views toward Italians and refusal to hire them for better paying jobs. In the large cities, tenements were essentially slums. If an immigrant couldn't get a decent living wage, they might reconsider trying to raise their family in America. Because Italian immigrants tended to be gregarious--often clustering together in "Little Italys", often they didn't feel there was a need to learn English, another factor in not being able to secure better paying jobs. Many might have fallen into the trap of getting housing or jobs through a padrone, a boss and middleman between the immigrants and American employers. The padrone was an immigrant from Italy who had been living in America for a while. He at first might seem helpful in providing lodging, functioning as safe "bankers" or money changers (often short changing), and found work for the immigrants (albeit, for a percentage of their earnings). Often, they would get the work that they could do in the apartments they rented to them... making silk flowers, rolling cigars, sewing, etc. After a few years of paying a percentage of their salaries to these padrone, many immigrants got discouraged enough to return to the homeland. At best, these situations became indentured servitude, at worst slavery. Child labor was also a product of these padrone, filling sweat shop factories with children as young as 10 years old. Prejudice Rears its Ugly Head Both immigrant contadini and those with skills faced economic as well as ethnic prejudices upon entering the labor force in America. The poor economy caused hostility toward Italians and many were labeled as strikebreakers and wage cutters from 1870 onward. American workers already feared the new mechanization in factories was the cause of taking away their jobs. Job bosses used Italians to fill their jobs as scabs during labor strikes. Prejudices were especially aimed at (as perceived) darker skinned Southern Italians who became scabs during strikes in construction, railroad, mining, long shoring, and industry. The Italian workers were called derogatory names such as:

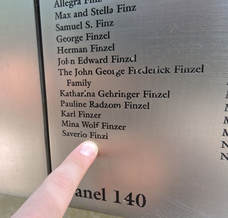

Italians were the only workers to work along side black people and employers preferred Slovaks and Poles to Italians. At the time, it was said that "railroad superintendents ranked Southern Italians last because of their small stature and lack of strength”. In the mining industry especially there was an ethnic hierarchy: English-speaking workers held the skilled and supervisory positions while the Italians were hired as laborers, loaders, and pick miners. It was not until the 1920s that Italians became more integrated into the American working class, regardless of whether or not they spoke English. More immigrants started to work at semi-skilled jobs in factories as well as skilled positions but one-third of the population remained unskilled. In trade unions, meetings were held in English and Italians were not elected to official positions.  Dad's name on the Ellis Island wall - Saverio Finzi Dad's name on the Ellis Island wall - Saverio Finzi My Grandfather, Sergio Finzi had made two preliminary Voyages across the Atlantic trying to establish connections and work so he could bring his wife and children over. He was a tailor, a skill he brought with him from Molfetta. They were poor. My father told of not having enough coal or wood to fire up their kitchen stove--the only heat in winter. He said he and his brother walked the railroad tracks to pick up scraps of coal fallen from passing trains. They left school in the fourth grade to help the his familia scrape a living from their new home. Many Italian immigrants suffered--and endured. We are all proof if this fact. Italian immigrants--as many immigrants from other lands--help build this country. They helped defend it. They assimilated. They became citizens. Paid taxes. Sent their kids to school. And here we are... over 100 years later and many in our country are still ambivalent or even dead against immigrants. Have we really lost sight of the fact that unless we have 100% Native American blood running through our veins, that we all are descended from immigrants? Starting in 1888, photographer Jacob Riis, a Danish immigrant, in an attempt to call attention to the suffering of immigrants, photographed the Manhattan tenement slums where Italian (and other) immigrants were living in squalor. He was followed by Lewis Hines, who photographed not only the immigrants and slums but the children who were the most helpless victims of this inflicted poverty. Enjoy the slide show... and try to remember the hardships our fore-bearers went through to get us where we are today... --Jerry Finzi At the beginning of 2017, we've started re-construction and re-organization of Grand Voyage Italy's pages. If you don't find what you are looking for on this new History page, use the Search Box to find what you need. Grazie!

|

On Amazon:

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed