|

Nowadays we buy all sorts of toys for our children, starting them off with the simplest ones: balls, pull-toys, rattles and such. When Lucas was a baby boy, his favorite was a cushy soft ball with a rattles inside--"Shakey Shakey"--he always like to squeeze it tight and shake it. Then there was his spinning top, the kind you pump down on for it to spin. Lots of twirling colors delighted him. Then there was his bouncer, with it's assortment of colorful gizmos for him to touch, hear and chew on. And at 13, he still sleeps with his oldest and dearest friends... his plush "Cushy Bear" and "Moo-Cow". Kids were always kids... even in the ancient world parents gave their kids toys...

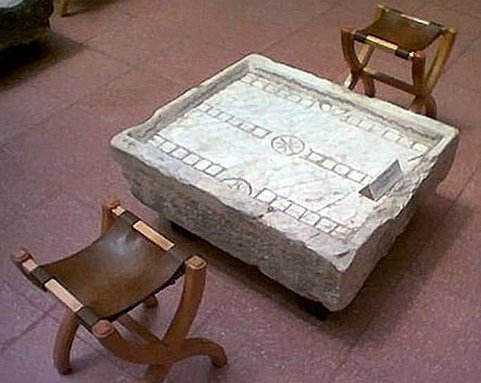

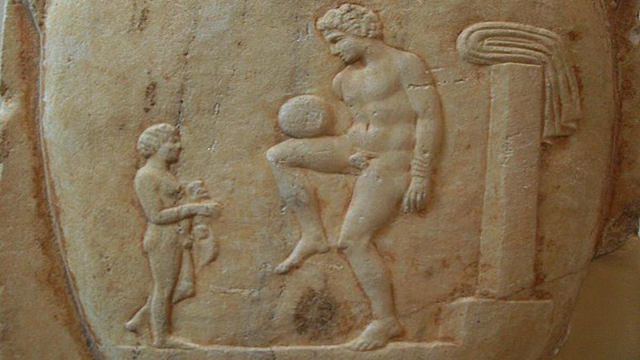

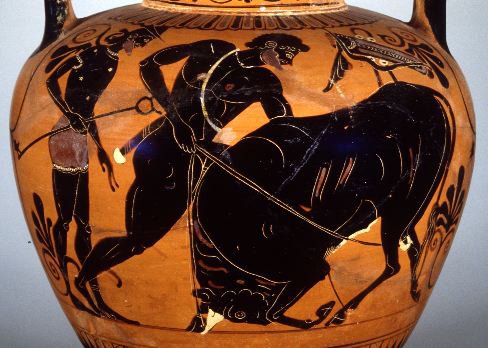

Of course, many first toys used by plebeian children were made from things found in nature: rocks, sticks, clay, acorns, pine cones, or vines or husks made into primitive dolls. Sometimes childhood fun is as simple as that. A game called Battledore, resembling badminton, used flat paddles hitting pine cones back and forth, or cork balls with feathers stuck into them used as the shuttlecocks. Pebbles could become a game with the dirt becoming a game board or a place to draw with a pointy stick. Just as today, one generation of children passed along ludos in plateis (street games) to the next. And of course there were dolls... made from fabric and stuffing, carved from wood or made from terracotta. Modern parents would have a hard time picturing a child cuddling up to a terracotta dolly. I wonder how many must have been broken in a tantrum during the Terribili Due (the Terrible Twos). For the toddlers, there were pull-toys made of terracotta or wood in all sorts of animal shapes. Some kiddies played with horses and chariots, just as modern kids might play with toy cars. One can imagine a young boy playing the part of the latest charioteer champion. As a boy got older, he might build a little cart to hitch a mouse to. As a kid, I remember putting my hamster behind the wheel of a remote control Model-T Ford model that I had... I loved watching him with his little paws on the steering wheel, going round and round. He seemed to like it, too. A mouse-drawn cart sounds like lots of fun, too.  Roman pig's bladder football Roman pig's bladder football The older boys and girls had outdoor toys... sticks and hoops, balls, yo-yos, swings, bow and arrows, sling shots, hobby horses, marbles, and games similar to kick-the-can, hide-and-seek and tag. And you can imagine some great racing games using toys with wheels on them... "My chariot can beat your ox cart! I'll bet 5 marbles that I can!" Of course, all a kid needed to do was have a ball and a stick and he'd make up a game. If he didn't have a ball, a rock or pine cone would do. When I was a boy we played stickball with an old broomstick and a cheap 10 cent pink ball called a Spalding (Spaldeen, we called it). Even thousands of years ago kids had games similar to field hockey or baseball or basketball. Borrow a basket from Mom (while she wasn't looking), start tossing some pine cones, and the fun would ensue. Sling shots--the same type David used to slay the Giant--came in useful to teach young boys how to hunt. And swimming was enormously popular for Roman boys. They would either go to a special swimming pool (Roman baths were too shallow for "plunging") or to the river. Boys were taught to swim as part of their formal education. Games were popular too, just like today. One of the most common was tic-tac-toe--played just as we do today, with Xs and Os. Some were carved into walls while most games were just scratched into the ground for temporary fun. Another similar game, Rota, was played with small stones on a layout that looked like pizza cut into 8 slices.  Box with sliding lid (missing) containing 2 dice Box with sliding lid (missing) containing 2 dice Cube shaped dice, as we know them, were around for at least 5000 years. There were always dice games, many for children and others for adult gambling. A precursor of dice, and a popular game, in and of itself, is Knucklebones (also called astragaloi), a game usually played with five or ten small bones. In ancient times, the "knucklebones" were the the actual knucklebones (astragalus--small ankle bones) of a sheep, although there are ancient "bones" made from precious gems, bronze or glass. The oldest version of a knucklebones game determined a winner depending on which side of the knucklebones landed facing up. (Both sides are distinctly different in shape.)  Knucklebones and Roman Dice Knucklebones and Roman Dice In another, the bones were tossed up in a manner similar to modern Jacks, with one knucklebone tossed into the air, and the player trying to pick up as many others as possible while it is airborne. Curiously, differently shaped bones would be worth different points. In another Roman game called Tali, the knucklebones are marked as dice are, with dots representing numbers--the resulting toss gives a player a hand to beat, similar to dice or playing cards. You can actually purchase Knucklebone pieces on Amazon.  Tabula shaking cup and dice Tabula shaking cup and dice There was also a game called Tabula that was very similar to backgammon of today, except it was played with three dice, but for most part, dice games of chance were left to adults--especially soldiers--for gambling. Still, boys have to learn the game from someone. I can imagine a father teaching his son how to play, as I've taught Lucas to play backgammon. An interesting fact is that when Greek and Roman girls, "came of age" (at 12-14 years old) it was customary for them to sacrifice the toys of their childhood to the gods. On the eve of their wedding, young girls around fourteen would offer their dolls in a temple as a rite of passage into adulthood. And yes... girls were married off after the age of 12.

Here are some other facts about what childhood was like in the Ancient World:

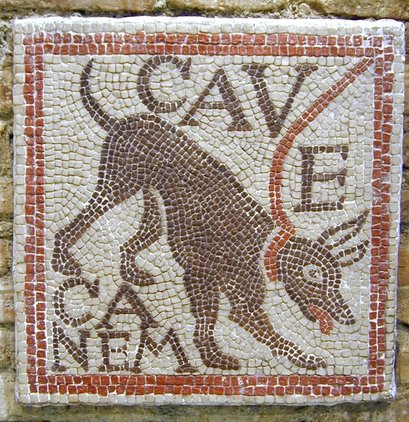

Bronze toy mouse Bronze toy mouse When a kid got bored with his toys, he could always spending time with his best friend, Il Cane, who might answer to Craugis (Yapper) or Asbolos (Soot) or Scylax (Puppy). The ancient Romans loved using Greek names for their pet dogs. Romans were great dog-lovers and had several popular breeds to choose from: hunting hounds, ratters and other small breeds that were bred for companionship and to keep their masters' feet warm in bed. Romans also loved birds, evidenced by various types shown domestic scenes in frescoes and mosaics. The odd thing is, cats were not liked in the Roman world, and even though might have helped rid them of rodents, were themselves thought of as pests. (Perhaps it's the Roman in me, because I feel the same way when roaming cats spray and stink up in my garden.) There are also mosaics showing children with pet goats hitched to child-sized carts, and even mice harnessed to miniature toy wagons. Unlike Italians of today, who tend to take a more practical view of animals, Romans loved their animals dearly. For example, modern Italians don't like to spend a lot of money on their pets--not even vets. Ancient frescoes and sculptures show Romans treating their pets as if they were members of the family. The dogs must have felt the same way, becoming protectors of their families, as illustrated by the many Cane Cavem (Beware of Dog) mosaics found at the portals of Roman homes. Here's a great batch of modern Roman toys (on Amazon) that your little ones can play with while they imagine life in ancient Rome...

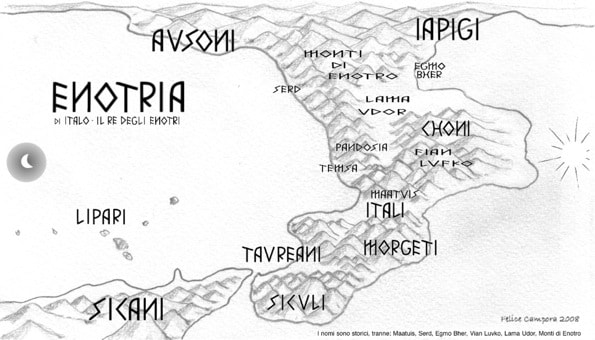

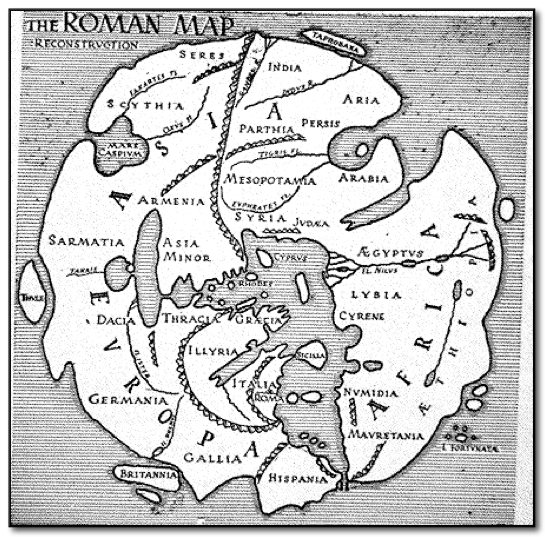

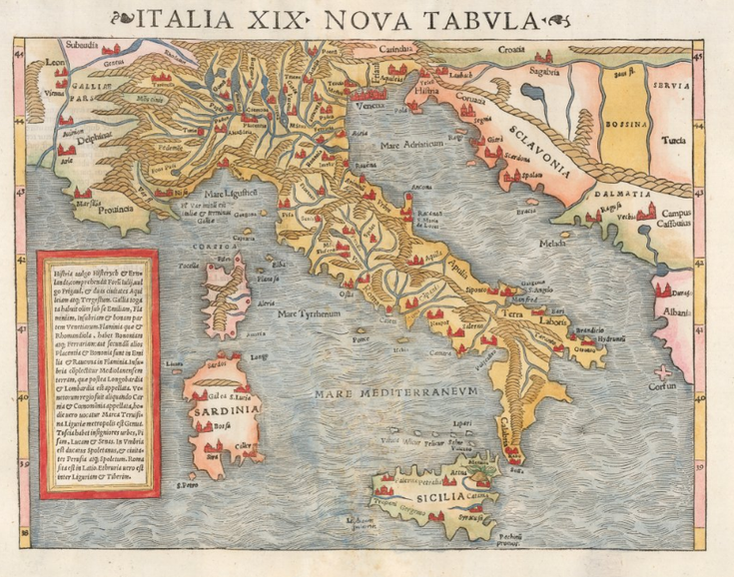

The name Italy (in Italian, Italia) evolved from variants of different names used in the ancient world as early as 600 BC in what we know today as the Italian peninsula. Historians are still researching its origins, but "Italia" surely evolves from Oscan word Víteliú (spoken by the Samnites), meaning "land of young cattle". A modern variant is vitello, the Italian word for calf or veal. In Roman times, vitulus was the word for calf. The ancient Umbrian word for calf was vitlu. Coins bearing the name Víteliú (𐌅𐌝𐌕𐌄𐌋𐌉𐌞) were minted by an alliance of several Italic tribes: the Sabines, Samnites, Umbrians and others who competing with Rome in the 1st century BC. Another theory is that the name stems from the Greek Italos, a legendary king of the Oenotrians, people of Greek origin who inhabited a territory from Paestum in the Campania to southern Calabria, among the earliest inhabitants of Italy. Italus was supposedly the son of Penelope and Telegonus, a son of Odysseus. It was both Aristotle and Thucydides who first told of Italus being who Italy was named after. The Greeks gradually came to apply the name Italia to a larger region covering most of Southern Italy, but it was during the 1st century BC that Augustus expanded the name to cover the entire peninsula including the Alps. The Greeks referred to these people as Italoi. Under Emperor Diocletian the Roman region called Italia was further expanded to include the islands of Sicily (including the Maltese archipelago), Sardinia and Corsica. Another reason for the name might come from the Greek word Aethalia, meaning "land of fog and smoke", referring to its many volcanoes. Mount Etna gets its name from the same etymological root. The Holy Roman Empire adopted the name Italia to describe its own territories in the central peninsula, and afterwards, the name was used to describe virtually the entire peninsula. In Middle English, the lands were called Italie. Later, in the 14th century, Dante described "Italia" as a land including lands from the Alps to the tip of the Italian boot, and including the islands of Sicily. The last theory intrigues me the most...

Eurystheus ordered Hercules to travel to the End of the World and bring him the cattle of the monster Geryon. Hercules succeeded in stealing the cattle but had enormous difficulty bringing the herd back to Greece. In Liguria, two sons of Poseidon, the god of the sea, tried to steal the cattle, so he killed them. At Rhegium, a bull got loose and jumped into the sea, swimming all the way to Sicily and then made its way to the neighboring country. The native word for bull was "italus," and thereafter this country came to be named after the bull. Perhaps this, stubborn, strong-minded bull is a perfect image for the naming of this amazingly resilient and tough country. Italia, Aethalia, Italie, Víteliú... and of course, the current day Italy is a never-ending source of history and amazing stories. --Jerry Finzi Were the ancient Romans ahead of their time? The famous Lycurgus Cup in the British Museum might be proof that they were indeed very advanced in the sciences, especially in the field of Nanotechnology. The 1,600-year-old glass goblet does something very magical: It changes color from jade-green to blood-red depending on the direction of its illumination... with the light source from the front, the goblet appears green, from the rear it changes dramatically to red. This is called Dichroic behavior. The Roman craftsmen who created this work of art either knew about the science behind it, or stumbled unknowingly onto its special characteristics. As they might have put it, felix accidente, a happy accident. The Romans may have been the first to discover the colorful potential of nano-particles by accident, but they seem to have created the world's most perfect example of the phenomenon. The Artistry of the Chalice The Lycurgus Cup is also a very rare example of a Roman caged cup, or diatretum. The glass has been painstakingly cut and ground back to leave only a decorative "cage" on the surface with extreme undercutting. Instead of the more common abstract, geometric design, the Lysurgus Cup contains beautifully detailed human figures. It shows the mythical King Lycurgus, who attempted to kill Ambrosia, a follower of the god Dionysus (Bacchus). She was transformed into a vine that twined around the enraged king, killing him. Dionysus and two followers are shown taunting the king. Such figures on a caged cup are otherwise unknown. History of the Cup The Cup is thought to have been made in either Alexandria or Rome around 290-325 AD, measuring 6 1/2" x 5". Judging from its excellent condition, it more than likely was never buried and was always kept as a treasure, at first in a noble Roman's villa, then in a church and later in the collections of the elite. There is also the possibility that it was recovered from a sarcophagus. The gilt and bronze feet were added late in its life--about 1800, making some think it was looted from the church during the French Revolution. It's more than likely that earlier mounts existed, but wore away with time and use. No one really knows the earlier history of the Cup. One can ponder about who it was originally created for, perhaps an emperor? The Science Behind the Chalice: Dichroism The Lycurgus Cup was mentioned in French writings as early as the 1845, but no one knew why it changed color. The British Museum acquired the Cup in the 1950s, but it wasn't until 1990 that researchers examined small broken shards under an electron microscope and discovered the secret. Whether or not the Romans stumbled into it, the artisans were truly nanotechnology pioneers. Nano-particles of gold in the glass on a microscopic level is the reason for the color change. (Gold added to glass makes red glass, as in stained glass windows). It's unknown whether the Roman artisans impregnated the glass with particles of silver and gold on purpose, or whether the glass was somehow already "contaminated" before they used it. Researchers found particles as small as 50 nanometers in diameter, less than one-thousandth the size of a grain of salt. Some think that exact ratio of the mixture of the precious metals suggests the Romans certainly did know what they were doing. This is how the technology works: When hit with light, electrons belonging to the metal flecks reflect frequencies into our eyes in ways that alter the color depending on the observer’s position in relation to the light. Was the Lycurgus Cup a Poison Detector? During the Renaissance, the ruling class believed that goblets and glassware made on the island of Murano in the Venice lagoon would vibrate and shatter when poison was poured into them. Although false--and likely just marketing hype aimed at the ultra-rich so they would pay more for glassware--perhaps this long held notion was based in some long-distant reality... a capability of cups like the Lycurgus, perhaps? Gang Logan Liu, is an engineer at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and has been focusing on using nanotechnology to diagnosis and treat disease. He explains, “The Romans knew how to make and use nano-particles for beautiful art. We wanted to see if this could have scientific applications.” Liu theorized that when a nano-treated vessel was filled with various liquids, the vibrating electrons would change the color of the glass according to the type of liquid used. The use the Lycurgus Cup to test his theory could never be allowed for fear of damaging a priceless Roman artifact. So he created this experiment: The scientists imprinted billions of tiny wells onto a plastic plate about the size of a postage stamp and sprayed the wells with gold or silver nano-particles, essentially creating an array with billions of ultra-miniature Lycurgus Cups. When water, oil, or sugar and salt solutions were poured into the wells, they displayed a range of easy-to-distinguish colors—light green for water and red for oil, for example. The prototype was 100 times more sensitive to altered levels of salt in solution than current commercial sensors using similar techniques. Were There Other Dichrioc Cups the Ancient World? Yes, it seems that the ruling class were well aware of them, owned them, gave them as gifts and drank from them on special occasions. However, only a handful of Roman dichroic glass objects are known to exist. Only 50 or so late Roman cage cups themselves exist, but even rarer, fewer than 10 dichroic glass objects have ever been found, and all of them (aside from the Lycurgus Cup) are mere fragments. Objects of such rarity with the extraordinary property of changing color would obviously be bought or commissioned by only privileged Romans. There are some ancient texts that discuss them... From Vopiscus' life of the third-century pretender Saturninus is a letter claimed to be written by emperor Hadrian (117–138) when he was in Egypt. Written in the early 4th century AD, Hadrian describes a gift to his brother-in-law Severianus in Rome: "I have sent you parti-colored cups that change color; presented to me by the priest of a temple. They are specially dedicated to you and to my sister. I would like you to use them at banquets on feast days" From the novel Leukippe and Cleitophon by Achilles Tatius (a second-century AD Alexandrian): The hero, Cleitophon, is at Tyre, where he attends a banquet given by his father on the feast day of Dionysus. During the meal, the host offers libations from an unusual vessel: "My father, wishing to celebrate it with splendor, had ... a precious bowl to be used for libations to the god ... Made of crystal... Vines crowned its rim growing from the cup itself, their bunches drooped in every direction. When the cup was empty, each grape seemed green and unripe, but when wine was poured into it, then little by little the clusters became red and dark, the green crop turning into the ripe fruit. Dionysus... was represented, near the bunches, as the husbandman of the vine and the vintner." Both of these texts describe very similar drinking vessels as the Lycurgus Cup. In the second text, you can imagine the cup from the drinker's perspective--filled with dark red wine, the outside of the cup was green. Then as the drinker lifts his glass and peers into it, the light passes through the side and it looks as if the grapes have turned red! The Lycurgus Cup was obviously a cup from Roman royalty that was treasured and cared for throughout the last 1600 years until modern scientists unlocked its secret. The Romans perhaps knew how to make and use nano-particles to create a beautiful object, but modern scientists think that nanotechnology can be useful in a wide range of scientific fields: chemistry, biology, physics, materials science, and engineering. Of course, perhaps equally amazing is the sheer beauty and artistry of the Lycurgus Cup. The capabilities of ancient Romans never cease to amaze me. --Jerry Finzi Watch the video below to see the changing colors...  September 11, 2018 Closed since 1997, the Cressoni Theater in Como was destined to be demolished, making way for modern luxury residence. As happens often in ancient Italy, the more you dig, the more you find... but what a find this was! A hoard of ancient Roman gold coins... A soapstone jar dating from the fifth century AD was found this week, full of ancient Roman gold coins that could be worth millions of dollars. The unique coins that date back to the late Roman imperial era were uncovered in the cracked soapstone jar, broken when workers first came upon it. “We do not yet know in detail the historical and cultural significance of this discovery but this area is a real treasure for our archeology,” Minister of Culture Alberto Bonisoli said in a press release published on Friday. As is common when archeological artifacts are uncovered, construction will be halted until further excavation is carried out by archeologists, who believe the site could also contain jewelry and gold ingots. The excavation site is close to the Foro Novum Comum, an area known for some major Roman artifacts discoveries. --GVI  In the town of Frattocchie, just south of Rome, you can now chow down on a Big Mac while looking under your feet, through a glass floor, and pondering an ancient Roman road. MacDonald's actually built this fast food restaurant on top of and around the road, making this their very first fast food restaurant and quasi-museum, complete with tours. But there's more... while the kiddies slurp their shakes, gulp their burgers and play with their Happy Meal booty, they can also gaze down at the 2000 year old skeletons of actual humans who apparently were cast aside into the road's culvert. Perhaps they were slaves who died and were tossed away as garbage, or they were soldiers who succumbed to a long and brutal march, or simply died of eating the wrong thing at the wrong time. (See what I did there?) The 150ft-long stretch of basalt road has been cleared, cleaned and made into a permanent attraction for customers, both inside and outside--under a glass floor. Tour guides take visitors under the floor to for a walk on the ancient pavement, but it's not clear if snacks are provided or food and drink is permitted. The truth is, finding ancient ruins while digging for new construction is not at all uncommon in Italy. The Roman Empire is literally everywhere... right under your feet. Happy dining, kiddies! --Jerry Finzi At the beginning of 2017, we've started re-construction and re-organization of Grand Voyage Italy's pages. If you don't find what you are looking for on this new History page, use the Search Box to find what you need. Grazie!

|

On Amazon:

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed