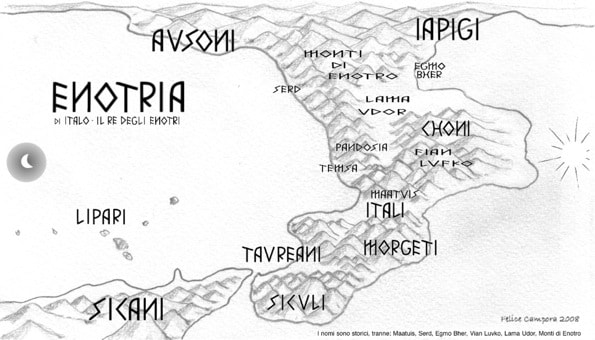

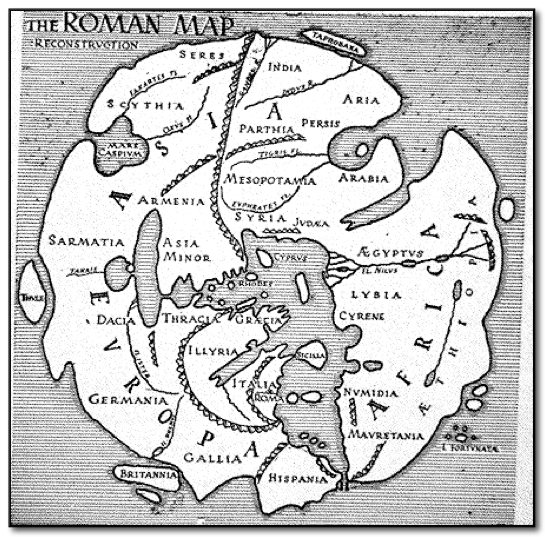

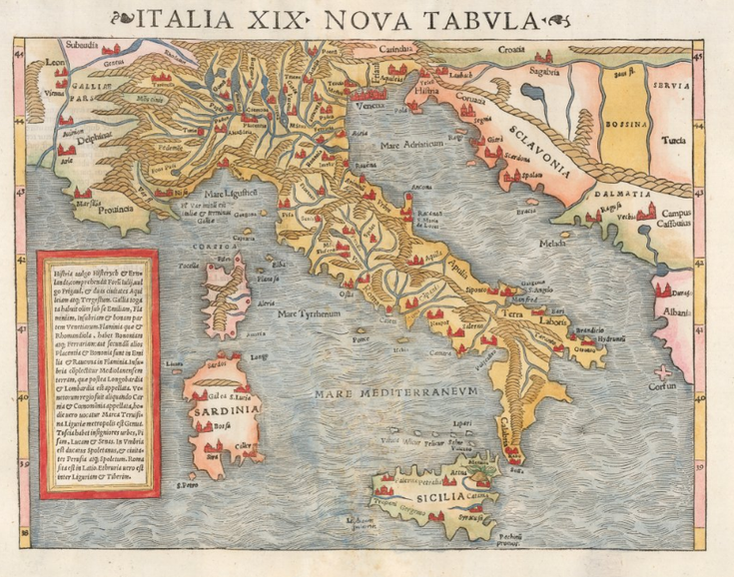

The name Italy (in Italian, Italia) evolved from variants of different names used in the ancient world as early as 600 BC in what we know today as the Italian peninsula. Historians are still researching its origins, but "Italia" surely evolves from Oscan word Víteliú (spoken by the Samnites), meaning "land of young cattle". A modern variant is vitello, the Italian word for calf or veal. In Roman times, vitulus was the word for calf. The ancient Umbrian word for calf was vitlu. Coins bearing the name Víteliú (𐌅𐌝𐌕𐌄𐌋𐌉𐌞) were minted by an alliance of several Italic tribes: the Sabines, Samnites, Umbrians and others who competing with Rome in the 1st century BC. Another theory is that the name stems from the Greek Italos, a legendary king of the Oenotrians, people of Greek origin who inhabited a territory from Paestum in the Campania to southern Calabria, among the earliest inhabitants of Italy. Italus was supposedly the son of Penelope and Telegonus, a son of Odysseus. It was both Aristotle and Thucydides who first told of Italus being who Italy was named after. The Greeks gradually came to apply the name Italia to a larger region covering most of Southern Italy, but it was during the 1st century BC that Augustus expanded the name to cover the entire peninsula including the Alps. The Greeks referred to these people as Italoi. Under Emperor Diocletian the Roman region called Italia was further expanded to include the islands of Sicily (including the Maltese archipelago), Sardinia and Corsica. Another reason for the name might come from the Greek word Aethalia, meaning "land of fog and smoke", referring to its many volcanoes. Mount Etna gets its name from the same etymological root. The Holy Roman Empire adopted the name Italia to describe its own territories in the central peninsula, and afterwards, the name was used to describe virtually the entire peninsula. In Middle English, the lands were called Italie. Later, in the 14th century, Dante described "Italia" as a land including lands from the Alps to the tip of the Italian boot, and including the islands of Sicily. The last theory intrigues me the most...

Eurystheus ordered Hercules to travel to the End of the World and bring him the cattle of the monster Geryon. Hercules succeeded in stealing the cattle but had enormous difficulty bringing the herd back to Greece. In Liguria, two sons of Poseidon, the god of the sea, tried to steal the cattle, so he killed them. At Rhegium, a bull got loose and jumped into the sea, swimming all the way to Sicily and then made its way to the neighboring country. The native word for bull was "italus," and thereafter this country came to be named after the bull. Perhaps this, stubborn, strong-minded bull is a perfect image for the naming of this amazingly resilient and tough country. Italia, Aethalia, Italie, Víteliú... and of course, the current day Italy is a never-ending source of history and amazing stories. --Jerry Finzi Museo Galileo - Museum of the History of Science in Florence  Galileo invented many mechanical devices besides the telescope, such as the hydrostatic balance, a pendulum clock and a high power water pump powered by one horse. Of course, his most famous invention was the telescope. Galileo made his first telescope in 1609, modeled after telescopes produced in other parts of Europe that could magnify objects three times. He created a telescope later that same year that could magnify objects twenty times. You might argue that although he didn't invent the first telescope, he obviously improved upon it. With this telescope, he was able to look at the moon, discover the four satellites of Jupiter, observe a supernova, verify the phases of Venus, and discover sunspots. His discoveries proved the Copernican system which states that the earth and other planets revolve around the sun. Prior to the Copernican system, it was held that the universe was geocentric, meaning the sun revolved around the earth His name doesn’t sound Irish when you read it in the Spanish naval documents, but Guillermo Herries (a Portuguese translation of his name) was really William Harris of Galway. It’s no surprise that Irish children never heard of “Guillermo” even though he was a member of Columbus’ First Voyage with the Nina, Pinta and Santa Maria…

As historians have theorized based on their evidence, William Harris first met Columbus at St Nicholas’ Church in Galway in 1477. Some say he discussed strange, unknown plant seeds and other objects washing up along the shoreline in Ireland possibly from some far off land, while others think Harris boasted to Columbus that he had actually sailed to those lands to the west. Columbus was also emboldened by stories he heard of the 6th century monk, St. Brendan and his voyage to the New World. It’s not too difficult to believe that Harris might have reached America before 1492, since it’s been proven that Leif Erickson had also been there hundreds of years earlier in a failed attempt at setting up a colony in the northern regions. “Guillermo Herries” is one of 38 people listed as being left by Columbus in Haiti to form the first European settlement in the New World. In the end, after a short time, the native population slaughtered them all. Still, we must honor both the Italians, Portuguese and even the Irishman that took part in opening up the New World to European culture… Happy Saint Patrick's Day a tutti! --Jerry Finzi At the beginning of 2017, we've started re-construction and re-organization of Grand Voyage Italy's pages. If you don't find what you are looking for on this new History page, use the Search Box to find what you need. Grazie!

|

On Amazon:

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed