|

First things first. Yes... "Espress" your love. Sitting across from each other with an invigorating espresso. Staring into each others' eyes. Memorizing every detail of that face. A sip and a sigh. It's just the beginning of the language of love in Italia... What do you call people engaged in amore? A boyfriend is a Fidanzato. The girlfriend is a Fidanzata. When both get engaged they are Fidanzarsi. Two lovers together are called La coppia--the couple. The lovers are called gli amante (the lovers) or simply amante. Ok, so you meet someone interesting and want to go on a date... The simplest was to ask is, "Vuoi uscire con me?" (Do you want to go out with me?) The date itself is called un appuntamento. When things start to go more romantic, you go on un appuntamento romantico. If someone stands you up for your appuntamento, they call it dare buca--giving one the hole or leaving someone in a hole. Here are some other phrases to learn in the event that you are looking for Love--or if Love finds you--in Bella Italia...

If you enjoyed this post, please share it with your friends... ciao! --Jerry Finzi The Physical Closeness of the Italian People One of the most obvious cultural events a visitor to virtually any town or village in Italy notices is a simple one: la passeggiata--the evening stroll. This isn't really an event. It's a cultural, daily habit of the Italian people. Instead of staying in each evening, families, friends and neighbors venture out and stroll together in the largest viale, piazza or strade principali. They stroll for social reasons. To be seen and to see. To stop with neighbors and listen to the latest political news or local gossip. They dress their best, as is the custom of la bella figura. They show off their new clothes, shoes or hairdos. They will see how pregnancies are progressing and show off how well the bambini are growing and flaunt their new puppy. Young teens fare la civetta (make like an owl, or flirt) and older singles check out who is available and perhaps meet up for an aperitivo in a street side cafe or some gelati. Both men and women will stroll arm in arm. When neighbors and cousins or school friends meet, they embrace and kiss, not once, but twice on both cheeks. They talk with their hands, often very excitedly, waving arms and making both subtle and dramatic arm and hand movements, oven combined with facial expressions or huffs and puffs. This is the language that runs the length of the boot from North to South. The Morning Ritual Each morning, millions of Italians have their breakfast standing up, shoulder-to-shoulder in local bars. The bar in Italy is not what you think. While they do serve a certain amount of wines and spirits, they are the place where Italians have breakfast: espresso and a sweet bread or tart, the most popular being a the crescent shaped cornetto. They have tarts, cakes, breads, and even sandwiches or pizza for lunch. They sip their strong espresso or cappuccino and have a morning snack while reading the paper or chatting with neighbors or work-mates. This is a social event at the beginning of each day. Long Lunches at Home Most Italians don't have lunch in restaurants. Most simply prefer to go home for riposa, that 3 hour lunch period from 12 noon until 3pm. Traditionally, pranzo (lunch) is considered the most important meal of the day. Even if they wanted to go to a restaurant for lunch, unless they are in a large city, like Rome or Florence, restaurants are also closed at noon. Italians prefer to spend the hot midday with close family at home and prepare hearty meals, and resting before returning to work. This affords even more hours that la famiglia spend together in close quarters... unlike Americans, who barely eat dinner together at the dinner table. Closeness of la Famiglia Another type of closeness is la famiglia itself. Although the average number of children Italians have is two, la famiglia living in one house or apartment are larger than you might assume. Aging family members in Italy are usually taken care of by younger generations, with sometimes as many as three generations living together in the same house--Nonna and Nonno, Mama and papà, i bambini and sometimes even an aunt or uncle or two. On weekends, extended families get together for pranzo di Domenica (Sunday lunch), either at a relative's home or a local agriturismo. When they eat outside the home, they all gather at long, family style tables, often seating 15-20. Often the meals are communal, served up in large trays or bowls, portions spooned out as needed. On some special holidays, such as during Natale, communal recipes like Polenta alla Spianatora is served on a bread board, with family members scraping polenta and sausages directly from the large board with their own forks. Crowded Sagre, Festivals and Events All throughout the year, regardless of season or region, there are literally thousands of festivals and sagre (food themed festivals) in Italy. Some estimates put the number of sagre at over 42,000! There are celebrations for nearly every type of cheese, wine, nut, berry, meat and pretty much everything else that can be grown and turned into something to eat, and nearly every type of animal: almonds, prosciutto, oranges, wild boars, donkeys, horses, Grappa, bread, pasta, chocolate, olives, fish... you name it, and there's probably a sagra to celebrate. As in the photo above, many events employ long family style tables for friends and strangers to dine together in the streets.  The crowds at the Siena Palio The crowds at the Siena Palio Then there are thousands of events like the Palio in Siena, that insane bareback horse race where 17 neighborhoods compete. Over 40,000 people jam pack into the Campo to experience this race. Then each contrada (neighborhood) have communal dinners for thousands on the streets. Take this one event and multiply by literally thousands... all over Italy, Sicily and Sardinia. People communing together, shoulder to shoulder. Living, loving, eating, drinking, dancing, soaking in la Vita Bella. Imagine how crowded the Venice and Viareggion carnevale are each year. Now picture the seasonal markets. And the New Year's Eve crowds and rock concerts. Over 60 million Italians crushing, standing, chanting, singing, eating, marching... tutti insieme (all together). Italy Has a Vulnerable Elder Population In fact, Italy has nearly 20,000 people over 100 years old and has held the worlds record for the oldest living human nearly every year for the last couple of decades. Italy also has the second highest life expectancy in the world, too--at 83 years young. The reasons for this aging population are varied. The Mediterranean diet, hills and steps keep people in general good health. People tend to retire earlier, giving a more relaxed, stress free lifestyle to the elderly. The midday riposa offers a way the oldest family members can still share in a meal and visits with younger family members, which we all know provides a healthy family environment. They often live with their children and play and hug their grandchildren, who we now realize might carry the COVID-19 virus without symptoms and pass it on to the older family members. Without the stress of how older people are going to have health care (there is national healthcare in Italy), Italians feel comfort in knowing that if something bad happens to their health, they will be taken care of, for little or no cost. The one factor that might actually make the aging population more vulnerable to COVID-19 is the fact that many still smoke. There are far too many smokers in Italy in all age groups. COVID-19 does well in patients with compromised lungs. But of course, people living to healthy old age is not the reason why many might succumb if they contract the disease. This virus is different and powerfully and quickly attacks the vulnerable. We should applaud the Italians living to ripe old ages, if only that they made it in a vivacious, healthy way. They often live with their children and play and hug their grandchildren, who we now realize might carry the COVID-19 virus without even knowing. Ferragosto, the National Vacation Then there's vacation time. Italians don't stagger their summer vacations over three months like Americans. Most of Italy shuts down for Ferragosto in August, the month-long holiday season when Italians head for their campers or beach bungalows and crowd the beaches along its 4,723 miles of coastline. They literally pack the beaches and campsites or head up into the cooler mountains. During summer, there are thousands and thousands of major and minor concerts from the Veneto to Tuscany to Campania and Puglia. Indoor concerts, outdoor concerts, music festivals in rock, folk, opera, jazz... you name the music, there's a festival to suit any Italian's musical tastes. Can the Spread of COVID-19 be Really Blamed on the Culture?

I would argue, no. How can anyone blame a culture for doing what comes naturally? Italians are gregarious. They have close knit families. They love to hold festivals for just about anything God has graced their land with. They hug and kiss and walk arm-in-arm. COVID-19 has taken all of this away from them--at least for now. But you can see the evidence of of Italians sharing even this in a joyful way by banging pots and pans on their balconies... and by making music with all sorts of instruments, again, from their windows or balconies. They sing Bella Ciao together as the WWI partisans did several generations before. They sing their national anthem. They light candles. Even though they are apart, they are together in wearing masks and gloves and battling this unseen enemy, as they have done in the past for thousands of years. They are partisans. The closeness of Italians is not to blame. The emotional closeness and comraderie of the Italian people are the cure for what is ailing them. Andrà Tutto Bene --Jerry Finzi  On the 6th of January every year, La Befana, the Italian witch, delivers treats to children across Italy, just as Babbo Natale does on Christmas Eve. But la Befana is a witch (albeit, a good one) who travels by broom, magically swishing down chimneys and leaving presents in children's pillow cases, stockings and shoes. In her hometown of Urbania--in the region of Marche--50,000 Italians celebrate this good witch's arrival with literally tons of desserts and foods. Throughout the streets and piazzas, you will find theater performances, fire-eaters, la Befana on stilts and also be amazed when she flies overhead (on a cable). The Festa Nazionale della Befana gives an alternative insight of holiday celebrations... it's perhaps one of the best festivals of the holiday season. --GVI Click on the photo above to watch a video of this festival

Most Italians take a two week vacation (called Ferragosto on August 15th) either before or after August 15th. Most large industries are closed during August and many museums and restaurants might also be closed. Many people take the entire month to rest and relax before returning to work and school on September 4th. The other period of time when holidays might affect normal business hours is the period between Christmas, New Year's Day and the Epiphany on January 6. Since Italy is a Catholic country, many national holidays coincide with religious holidays.

In addition, all Italian cities celebrate the patron saint as a legal holiday. All businesses are closed on...

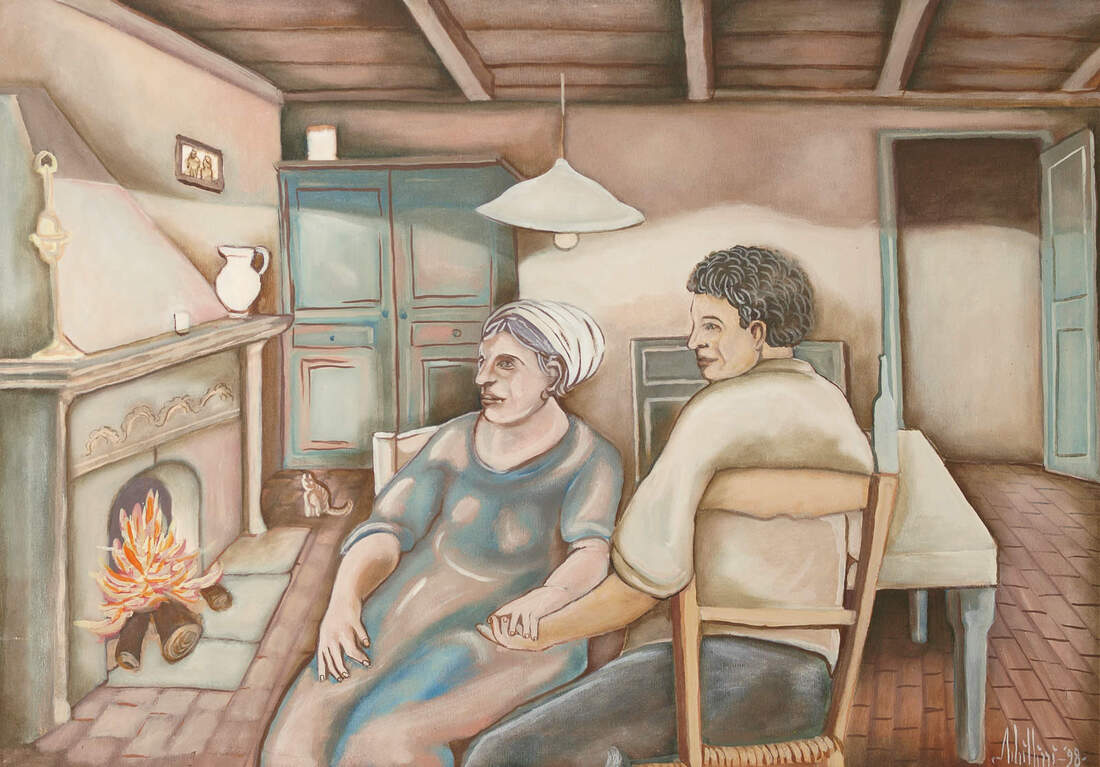

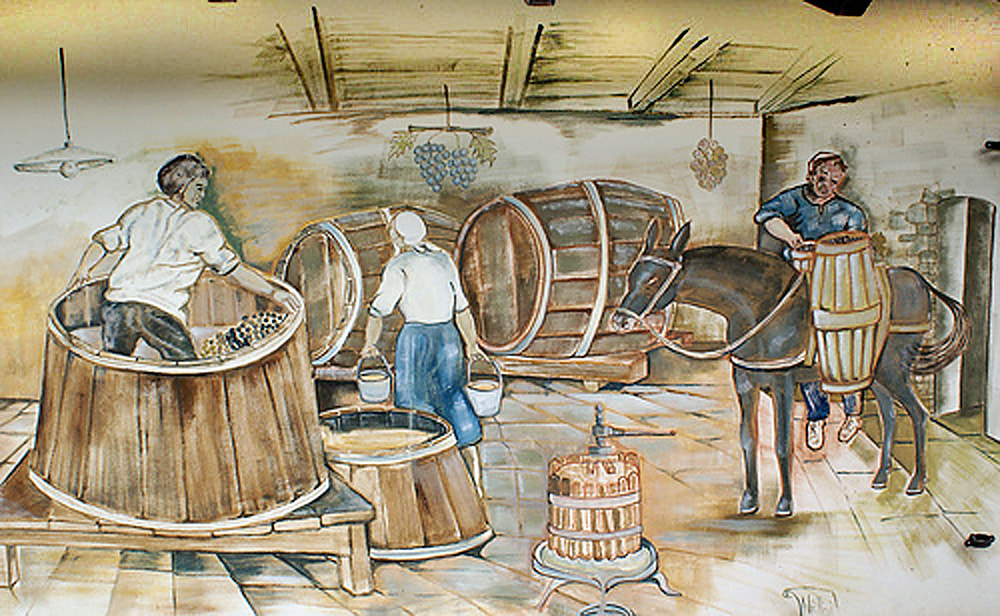

Schillizzi Schillizzi Enzo Schillizzi (b 1955 - d 2009) lived in the small Albanian-Italian village of San Costantino Albanese above the banks of the Sarmento River. The artist spent almost all his life in this small village just outside of Potenza, painting the local life and culture in murals all around the area. His work focused on the cultural symbolism of arbëresh tradition and folklore, especially on religious rites, for example, illustrating Nusazit, the pyrotechnic puppets of the saints day of San Constantino Albanese. Proud of the region's heritage, he recorded his impressions of the romantic and violent history of Basilicata and the briganti, robber/rebels who ran rampant during the post-unification period if Italy. Other subjects were his own interpretations of of painters such as Velasquez and Picasso. Some works are childlike, with indeed a Picasso-esque loose hand, while others show his extraordinary skill as a draftsman. After his untimely death, in July 2009, an effort has been made to research, document and restore and preserve his wonderful murals in addition to paintings privately owned. His colors often remind the viewer of the muted and natural palette from Basilicata itself--wheat, the varied tones of greens from the mountains and valleys, and the more vibrant colors of sky and flora. This research has been possible through the efforts of family and friends, who helped to identify and search out several paintings and gain permission of the owners to allow photographing them for posterity. Despite his works being dispersed in various places, a significant number still remain in San Costantino in private collections houses and in public spaces. Some his more complex works remind me of the work of Mexican muralist Diego Rivera while others have a mix of abstract and cubism in their compositions. After seeing his work, I'm convinced that his imagery would be well suited to ceramics and mosaic tiles. The town of San Constantino is blessed to have much of his work on public display, honoring their wonderful heritage. --Jerry Finzi  Procession in Itri, Lazio leading their way toward the bonfire Procession in Itri, Lazio leading their way toward the bonfire In Puglia, Basilicata, Lazio, Umbria, Lombardy and other regions of Italy, many towns and villages celebrate la Festa di San Giuseppe (March 19th) in a unique way... by lighting Fuochi nella Notte, fires of the night--or bonfires. The bonfires and festivities are on various days (depending on the town), from March 17th through the 19th. Known by different names, the bonfire festival might also contain the words Torciata (torch), Fiaccolata (torchlight procession), Falò (fire). For example, in Tuscany's Pitigliano, the event is called Torchiata di San Giuseppe with people dressed in medieval costumes and a procession of men and boys dressed in hooded monk's robes carrying flaming reed torches that will help build the bonfire. After the bonfire has burned down to ashes, tradition calls for people to collect and keep the ashes, ensuring their good luck in the coming spring. As with other holidays beginning in the New Year and throughout lent, the lighting of bonfires has a long history going back to the time of pagan worship. Through the last 2000 years, the activity has morphed into a Christian tradition. This tradition also coincides with the need to burn the trimmings from vines, olive trees and other woody crops. While Christians claim the fires are a representation of the good father, Saint Joseph, striving to keep the infant Jesus warm during winter nights, others say the tradition is from the ancient Romans celebrating the dark winter being overtaken by the light of spring. Many modern observers say it's just another way for fun-loving Italians to throw yet another party, for as with most festa and sagre, there is always the food, and a great sense of community.

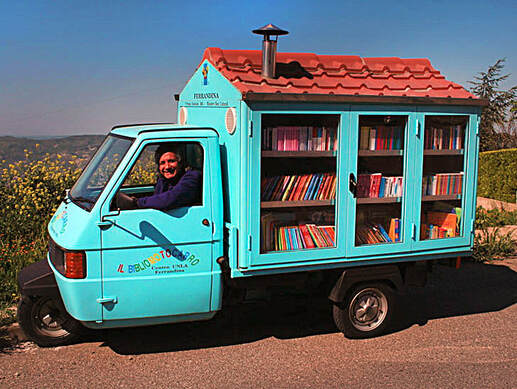

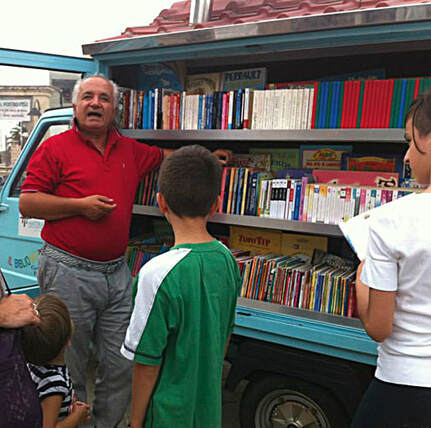

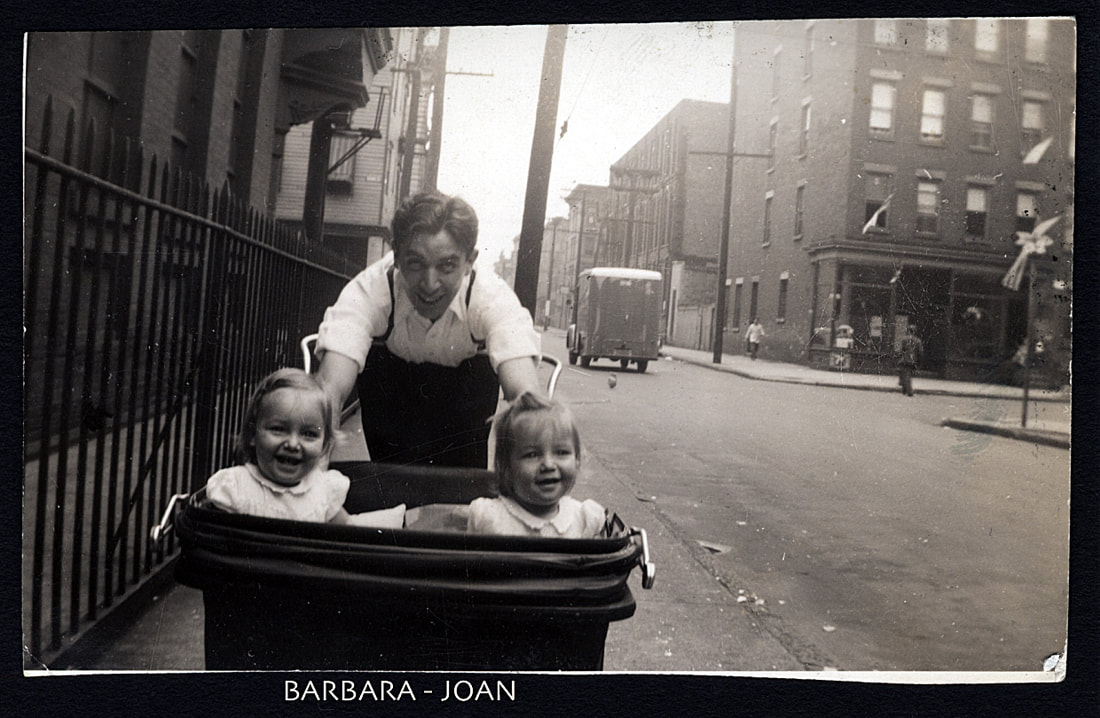

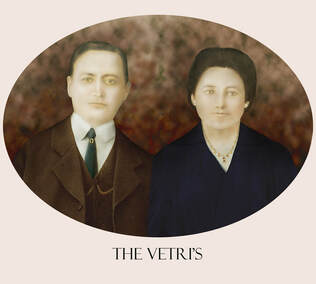

And if the truth is to be told, Italians love bonfires so much, you will also come across other Fuochi on other saint day festivals across Italy. --GVI Italy is know for passionate people, and Antonio La Cava from Matera is one of them. He's passionate about sharing the glory of books with children. La Cava carries a telling surname, as Matera is the city of caves, or Sassi, when people have been living in cave homes for tens of thousands of years. Retired as a schoolteacher after 42 years but couldn't stop spreading knowledge to il bambini of his region of Bacilicata. So in 2003 he bought a used tre-ruote (three wheeler) Ape mini truck and created his Bibliomotocarro, a portable library that houses 700 books. La Cava travels over 500 kilometers each week to 8 regular stops on his route. The children know of his arrival by the sound of organ music coming from his unique vehicle. The children run to greet him as if some TV star is showing up. He also funds his efforts, pays for fuel, repairs and buys the books from his own pocket. His passion for the love of the written word will be carried on--certainly by the many children on his route. --Jerry Finzi “A disinterest in reading often starts in schools where the technique is taught, but it’s not being accompanied by love. Reading should be a pleasure, not a duty.” --Antonio La Cava Being a second-generation Italian-American, I wasn't affected by the Italian naming conventions. I once asked my mother why we never spoke Italian and she answered, "When we got married, I wanted an 'All-American" household, so we only spoke English around you kids." I'm certain one reason for this was to lessen the impact of racial bias against her kids at the time. This might also be the reason why I was named "Jerry"--as my mother told me, "I thought of 'Jerry' after watching a Jerry Lewis movie while I was expecting you. It sounded very American." While my birth certificate says "Jerry", I had no idea my legal name was "Jerry" until at age 13, I got a copy of my birth certificate to get my working papers. "Jerry"? Well, that was a lot better than "Gerald", my baptism name, which I could barely pronounce properly when I was little. Even so, everyone in my family knew me as "Gerald" until I ordered them to stop calling me that. Still today, many won't call me "Jerry". (To add to my confusion, Saint Gerald was French!). Being the second born son, I should have been named after my mother's father, Salvatore Vetri. That would have been nice, since my Dad's lifelong nickname was Sal, even though he was born Saverio. Since I was born 11 years after Salvatore's passing, perhaps my mother felt less obliged to name me after him. My sisters and brother who came before me met the same fate with their names. The oldest of us--the twin sisters--Barbara and Joan should have been named Caterina and Mariantonia, Caterina being my paternal grandmother's name, and my maternal grandmother being Caterina. (Barbara was the oldest by three days... YES, they were born three days apart, but that's another story.) Kenneth, my older brother, should have been named Sergio, after my paternal grandfather. My sister Joyce should have been named after one of my aunts, perhaps Antonia or Rosa. Although I know that Barbara, Joan, Kenneth and Joyce are my siblings, I have no idea who they were named after since those names are unknown in our family tree. Only their middle, confirmation names reflect names of uncles or aunts. Perhaps other movies my mother watched while she was pregnant for each of them influenced her... The twins? Barbara Hutton and Joan Crawford were famous during the 1940s when the Twins were born, Joyce Reynolds was a well-known, All-American looking actress when my sister Joyce was born. But Kenneth? There really were no famous actors or performers named Kenneth when my brother was born--and it's a very British name, at that. Mom probably just liked the sound of it. As for me, I really think I would have preferred to be named Francesco, Giovanni, or even Anselmo after one of my my uncles. "Jerry" never really suited me. And here's an interesting note about my father's name, Saverio... There is no Saverio in our family tree, and since my great-grandfather Anselmo was adopted, there was no maternal grandfather to name him after. It seems the name was given to my father (second son of Sergio) as a "votive name". Saverio means "second home" or "new home". My grandfather traveled to America 2 times before bringing over is wife and three children, 7 year-old Anselmo (named after my great-grandfather), 4 year-old Saverio and baby Antonia. Perhaps Saverio was born at the moment my grandfather decided to take the first steps on emigrating. Saverio. New Home. It suited Dad. How to properly name an Italian child... . The basic convention goes like this:

Be aware that there are exceptions to this naming custom that preclude this assuming your ancestors adhered to these conventions. In the case of orphans, they would have no idea of parents' names. For someone estranges from his family, he might not want to use their names. It is also possible that the first born son might have died, so they might have also given the same name to a second born son who survived. Many children did not live to adulthood in the nineteenth century and earlier. It is also very possible that your ancestors didn't keep to these conventions, for instance, many named their first sons after a hero. For example a hero in southern Italy (The Two Kingdoms of Sicily) in the early 1800s was Guglielmo Pepe, so an ancestor in this time period could be named after him. A final example of exceptions to the naming custom can be seen in the nontraditional family of my great-great-grandparents, Pasquale and Rosa. They were great opera fans who named all of their children after characters from their favorite operas. Due to theses types of exceptions, you cannot use the Italian naming tradition to assume an ancestor's name. When doing genealogical research another problem can arise when finding several people living in the same town at the same time, all with the same first and last name. Think about it a second. If someone named Giovanni had five sons, all of them could have named their first born sons Giovanni, resulting in confusion as to which one is your gr-gr-grandfather and which are merely distant uncles. The same would hold true when researching the maternal members... Nonna Rita might have several Ritas that were named after her. They might even have been born in the same year! Remember, families were often quite large, especially in the rural, agricultural south. This shows that although it seems naming conventions might help you discover your ancestors, they might also confuse the issue. When in doubt, it might be a good idea to hire a genealogical research professional to make sure you find the right people in your family tree. --Jerry Finzi For help in researching your ancestors, the Facebook group

Italian Genealogy is highly recommended by GVI. There are several professional researchers who are members who freely offer their advice and who can be hired to help find your ancestors.  by David Dalessandro from Sharon, Pennsylvania Need some guidance here, so I thought coming to my paisans at Italian Gardeners on Facebook would be a good place to go... While pulling my tomato plants today it hit me that I was alone. My knowledge of gardening, weak as it is, came most from my Father who got his knowledge from his Father who was an immigrant to the U.S. from Foggia. My grandfather worked for Carnegie Steel in Farrell, PA as a janitor for the office. Carnegie had provided a home for him at a cost of $2.200. Company homes without a bathroom were $2,000 so Pasquale went for the better model. Companies did that in those days...this was 1925. The company then deducted so much from his pay and he had a decent house where he could walk to work. Another thing the company did for employees was to provide garden space. Carnegie owned extra land in Wheatland, PA and the company would plow the land--at no cost to workers--and let employees claim part of it to put in their own garden. My grandfather took great advantage of that and every year would plant tomatoes, potatoes, beans and other vegetables that would help to feed his family. It was in this garden that he taught my Father, who then taught me. So, fast forward to today, about 80 years later. I am stuck on the Teaching Thing. My children are grown and not really interested. My daughter is in El Paso, Texas and my son, still living with us, is working to become a tennis professional. Neither are much interested in gardening.  100 year-old Portland gardener, Ulisse Edera. Photo by Keith Skelton. 100 year-old Portland gardener, Ulisse Edera. Photo by Keith Skelton. But I love it. I enjoy starting the seeds, tilling the ground, fertilizing and watching the plants grow. Because of the abundance God has provided, I also can many jars of tomato, sauce and hot peppers. Again, not because I have to, like my Grandfather had to, but because I want to. But, I am afraid that I am the last of the line. My uncles are gone. My Father is gone. My wife humors me and lets me do my thing in the garden. It bothers me that it is likely to end here. And, I fear I am not alone. No one at work talks about a garden. No one else in the neighborhood has one. Just me. It is a shame, I think, that the accumulated knowledge of at least three generations will end. Do any of you have the same concerns? Do you have children or grandchildren who work with you and ask questions and help pull weeds and can tomatoes and wonder why something is growing or not? Let me know...and if you have answers for this situation, I would love to hear them. Thank you so much, my paisans.  Passing on the tradition Passing on the tradition And my Thoughts... And I totally agree with David, which is why I've asked his permission to post his words here on Grand Voyage Italy. After all, we are #AllAboutItaly here... and we're all about the Truths about our culture. I feel David is correct--too many young people today are detached from their cultural roots and have no idea where their food comes from, especially true with Italian-Americans. When one takes a Voyage around Italy, all you see is gardens--everywhere, in tiny front yards, hanging on walls, on balconies and terraces and in pot gardens surrounding people's front doors. It doesn't matter if they have lemons and pomegranates on their patio or just a pot of basil on their windowsill--it seems that everyone grows something edible. We should all strive to teach our children the value of home grown, healthy food, like I've done for my own son, Lucas. Here's a photo of him with his tomato harvest at 4 years old... He's 15 now and looks forward to each February when we go down into the cellar, sort out our seeds and start our heirloom seeds that we save each year from our garden. He now looks forward to the tomatoes we grow as if they are old friends... Eva Purple Ball, Olivette Juane, Giant Belgium, Jersey Devil and more. He also is learning to cook using the vegetables harvested from our garden, and even when we don't grow them ourselves, he now knows how to smack a cantaloupe, listening for the lowest pitched sound (a sign of ripeness), or check a peach's ripeness with his nose, as my Dad taught me. Gardening is part of the Italian soul. Pass it on, people. Pass it on... --Jerry Finzi And for more on the subject of gardening... Creating a Hanging Italian Wall Garden

Bicycles - Italian Garden Style My New Favorite Tomato: Striped Roma San Marzano Tomatoes: Accept No Imitations! How the Tomato Became Part of Italian Culture Only in Italy: Strange Veggies from La Belle Paese To see how you can create an Italian Garden of your own, check out the Grand Voyage Italy Shop on Amazon. |

On AMAZON:

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed