|

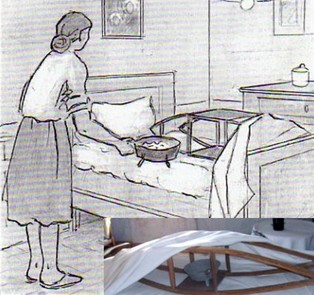

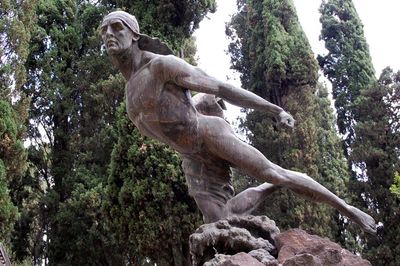

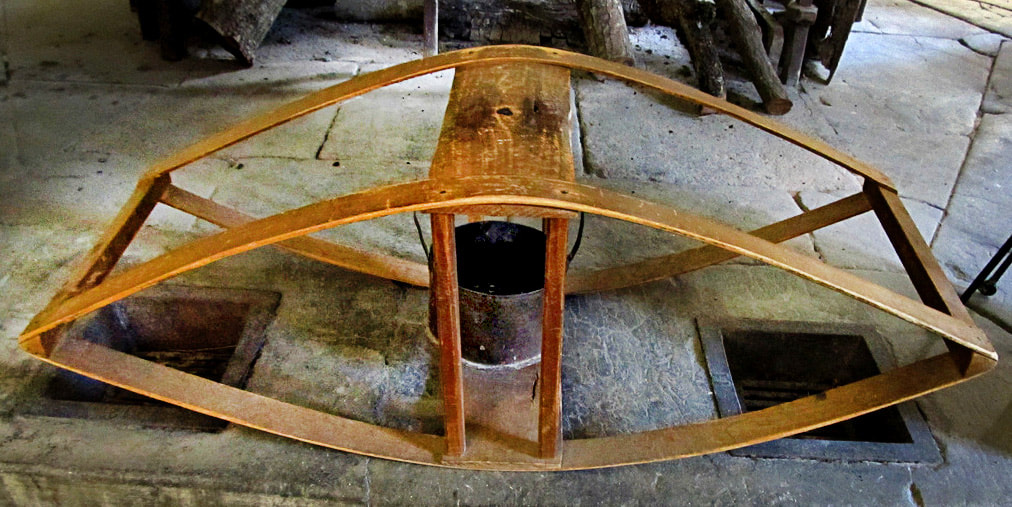

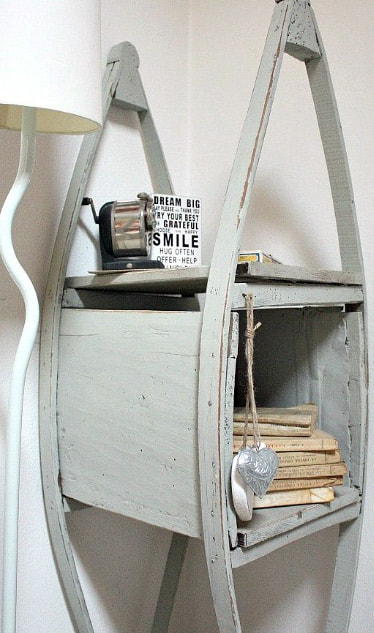

When I lived in Paris years ago, one of the most unexpected pleasures was when I visited the Père Lachaise Cemetery. Often, people regard this unusual site as a place of pilgrimage, to pay homage to the likes of Chopin, Edith Piaf, Oscar Wilde or even rock legend Jim Morrison (his grave littered with graffiti and drug paraphernalia was distasteful to me). But I went for a different reason... the art. Admittedly, wealthy families could possibly afford to commission a granite temple, travertine pyramid or marble sculptures to honor a lost beloved member--and truth be told, perhaps the effort is really a monument to perpetuate the myth of their family's importance for the ones still living and yet to come. In any case, I didn't visit to pay homage to any heroes of mine. I went for the art itself. In Italy, it's also possible to do the same as a number of cemeteries contain some amazing monumental art.  Photos of family members passed are lovingly cared for Photos of family members passed are lovingly cared for Most modern Italian cemeteries sit on the outskirts of their towns and consist of a mix of traditional graves and headstones and multi-level rows of vaults, a method used by the both the ancient Etruscans and early Christians. The vaults are simple affairs, sealed with a marble stone, names and dates with a small medallion containing a photo of the individual as they appeared in life. However, over the years, many wealthier families commissioned architects and artists to create chapels, tombs and sculptures resulting in many Italian cemeteries becoming open-air museums of funerary art, known as Cimiteri Monumentali (Monumental Cemeteries). I've put together a collection for you to enjoy... --Jerry Finzi  Cemeteries Worth Visiting Monumental Cemetery of Staglieno One of the largest cemeteries in Europe, the Cimitero Monumentale di Staglieno in Genoa covers nearly a square mile on the hilltop district known as Staglieno. It was opened in 1844 at a time when Genoa was home to affluent bourgeoisie businessmen, politicians and artists. To honor their accomplishments, realistic sculptures were commissioned for their tombs. This is without doubt, one of the most visited monumental cemeteries in Europe.  San Michele Cemetery, "Island of the Dead", Venice After the fall of the Venetian Republic in 1797, Napoleon prohibited any burials in town centers and in Venice, this meant that a new walled cemetery was commissioned on the island of San Michele, within reach of gondolas from the Venice waterfront. The island is landscaped with tall cypress trees, a 15th Century church and cloister. The shallow graves are occupied a dozen years and afterwards are exhumed with the bones interred into mausoleum niches or dumped into a communal ossuary. You'll find graves of 19th and 20th Century foreigners, including celebrities like Ezra Pound, Serge Diaghilev (whose grave normally is decorated with a ballet slipper), and Igor Stravinsky.  Cimitero Monumentale di Torino The Monumental Cemetery of Turin was commissioned in 1827 to replace the small and ancient cemetery of St. Peter in Chains. It contains numerous historical tombs and 6 miles of porticoes adorned with sculptures of artistic interest.  Cimitero Monumentale di Milano One of two large cemeteries in Milan (Cimitero Maggiore is the other), Milan Monumental Cemetery was designed by architect Carlo Maciachini and contains a multitude of sculptures by renowned artists: Giò Ponti, Arturo Martini, Lucio Fontana, Medardo Rosso, Giacomo Manzù, Floriano Bodini, and Giò Pomodoro. Visitors enter through an impressive Medieval style building of marble and stone that contains the tombs of the country's most honored citizens. Besides having mostly Catholic graves, there are also sections for Jews and other non-C Catholics. The cemetery contains the tombs of composers Corelli, Verdi and Toscanini.  Cimitero Monumentale di Messina The Monumental Cemetery of Messina, in Sicily, is one the best for funerary art. In 1854, it was designed as a urban park and gardens as well as a cemetery. The cemetery is divided into the Jewish cemetery, the Catholic cemetery, and a monument to the victims of the First World War. The art in this cemetery is second only to Monumental Cemetery of Staglieno in Genoa.  OK. Now, don't scream, "sacrilege". Let me explain... More than 100 years ago in Italy, people really would place the Nun and Priest into their beds to warm things up. The Suora e Prete (Nun and Priest) was the name of a device used to warm the bed and blankets just before bedtime. In northern dialect, they might be called Frà dël let, or Bed Brother. They were often used until the early 1900's, and perhaps even later on in poorer parts of Italy. The Nun, or scaldaletto (warming bowl), was a removable round bowl with handle, into which hot coals (with ashes to slow down their cooling) were placed. Placing hot bricks in place of the Nun was also an option. Wealthier folks could afford rocchetti--small cylindrical containers filled with compressed coal dust. They were heated in the fireplace and lasted a lot longer than loose coals and ash. The Priest constituted a frame that housed the Nun along with its hot embers, holding sheets and blankets well above the coals to prevent them from scorching or bursting into flames entirely. Sometimes the Nun had a lid with decorative perforations which allowed the heat to escape. The Nun and Priest also helped dry the damp sheets--a common problem in the cold and damp of stone houses during the winter months. What are the roots of the name? Many consider the draping bed coverings to look like the draping of a nun's hood. Why "Priest" then? With Italians' tendency to be shockingly irreverent, we can only guess. Perhaps there is a reason the priest is on top... of course, I mean to hold in the heat of the Nun under "him". Wait... I'm getting myself into trouble here.... The interesting thing is, the Nun and Priest is still being made today, albeit in electric versions. When considering the thick stone walls and dampness of old Italian houses, this contraption might seem like a very good idea to warm up the bed on a cold windy night. Very common in Italian antique stores and flea markets, many people have taken to finding new uses for the Nun and Priest, especially as decorating objects. The Monk, a Close Cousin... Another tool to heat the bed was il Monaco or also Mariteddu (the Monk), a kind of terracotta amphora that was filled with boiling water and placed under the covers. The rather thick, heavy ceramic would retain heat for long periods of time and release it slowly, creating a gentle warmth under the covers. Unlike the Nun and Priest which warmed the bed before you got in, the Monk could be kept in bed during the night with you. Oh no... here I go again. I'll stop now. --Jerry Finzi This might also interest you...

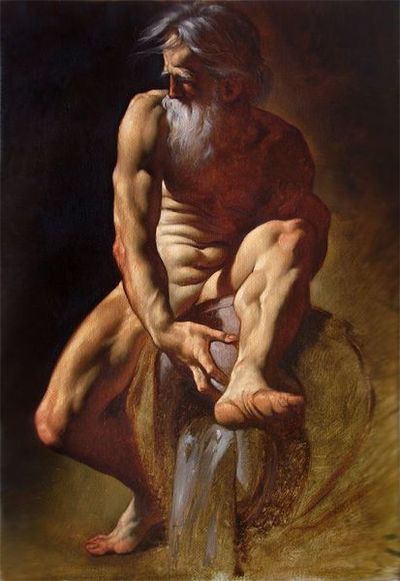

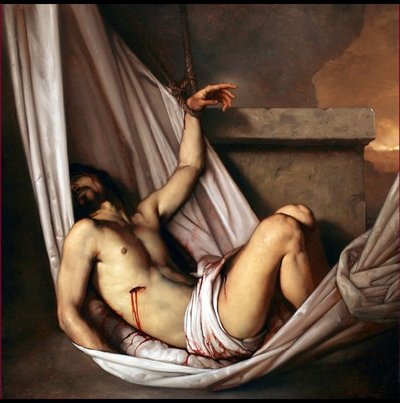

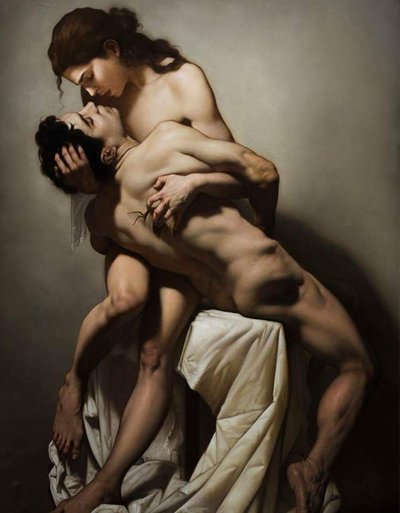

Italian Warmth from the Poor Mans' Hearth: Il Braciere, the Brazier Roberto Ferri, born 1978, is an Italian artist and painter from Taranto, Italy. He is deeply inspired by Baroque painters (in particular Caravaggio) and other ancient masters of Romanticism, Academism, and Symbolism (David, Ingres, Girodet, Gericault, Gleyre, Bouguereau, Moreau, Redon, Rops, etc.) Graduated - with honors - Academy of Fine Arts in Rome. In 2003 - first one-man show "Roberto Ferri and the dream of Parnassus" in the Center of Contemporary Art in Rome. His works are already present in many important private collections in London, Paris, Madrid, Barcelona, Miami, New York, San Antonio, Rome, Milan, Malta, Dublin, Boston, and the Castle of Menerbes, Provence. “Each of my paintings carries a message containing symbols and allegories whose interpretation depends on the viewers: the message travels in two opposite directions concerning both intellectual tension and perception.”

Until recently, Christmas in Italy was exclusively a family feast, and children only received gifts on Epiphany (January 6). After leaving out a bottle of wine and some slices of salami to appease La Befana the night before, in the morning they would discover sweets and gifts left in their stockings and shoes. The presents were traditionally a piece of fruit or candy, but naughty children might also receive a lump of coal.

This tradition has morphed into leaving gifts not only in stockings or shoes, but giving gifts of edible chocolate shoes filled with treats. Obviously, with chocolatiers making very high quality pieces of art in the form of shoes, this tradition is not just for little ones any longer...  Now that the New Year is behind us, the fireworks smoldering out, the empty bottles of Prosecco dumped into the recycling bin and our stomachs filled to the breaking point, you might think that the holiday is over. In Italy, the Season has another week to go... Christmas time in Italy is not finished until the Epiphany on January 6th (giorno della Befana). In essence, the Twelve Nights of Christmas come after December 25th. On the night of the Epiphany, children wait for the Befana the Christmas Witch who--according to Italian folklore--arrives on a broomstick, comes down the chimneys and fills kids’ stockings with sweets, chocolate or a lump of coal for those who have been naughty. Children will hang stockings on the mantle for Befana to fill, even though the modern custom of receiving gifts on Christmas Day is also enjoyed. In parts of northern Italy, the Three Kings might bring your present rather than Befana. And even though Babbo Natale (Santa Claus) might have brought them some small gifts on December 25th, the main day for present giving is on Epiphany. Many Italians continue the Holiday season by taking a trip down South if the weather is warm or up North or to the mountains where they can enjoy some skiing. The week following Capodanno is for family gatherings, vising distant relatives or simply spending time at home with their children, who are home on Christmas break until after the Epiphany. In some towns, Christmas markets are still running strong:

Trento: from November 22, to January 6 (closed on Christmas day). The Trento Christmas market will be twice as big with wooden huts selling Christmas and traditional goods both in Piazza Fiera and Piazza Cesare Battisti. The traditional Nativity Scene will be hosted in Piazza Duomo. Levico Terme: from November 22 to January 6. Rovereto: from November 22 to January 6. Arco: from November 21 to January 6. Merano: November 24th - January 6th on Piazza Terme and surrounding streets. Vipiteno, South Tyrol: November 24th - January 6th, Piazza Città Naples, Campania: any time of the year, visit artisans that create presepe and character figurines and accessories. On Via San Gregorio Armeno |

On AMAZON:

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed