Many Americans think there isn't a holiday like Halloween in Italy... but there is. On November 1st, Italians celebrate La Festa di Ognissanti, or All Saints’ Day. This is a national holiday when post offices, banks, and schools close, as well as being a Catholic holiday honoring all of the saints, martyrs and ancestors who have gone before. Italians will decorate and light up their cemeteries for Ognissanti, but in recent times they also carve pumpkins and even dress up for local festivals. A common tradition is to for a family to visit the cemetery after a special feast, to visit the members of family passed, leaving a tray of food for them to enjoy at their tomb. This visit leaves their home empty so that the dead could come back for a short visit, but without either the living or the dead disturbing each other. Families return to their homes and the dead return to their graves after church bells are tolled. Depending on the region of Italy, some burn bonfires and kids might do something like Trick or Treating from home to home (chanting "Morti, Morti") and receive treats. There are many variations throughout Italy, some even predating Halloween traditions. Many leave food out all night in case the dead want to come back home and feast while they sleep. Here are some Italian words to tide you over during this interesting holiday...  Una Strega - Witch Scopa - Broom Pipistrello - Bat Ragno - Spider Osso - Bone Cranio - Skull Grondone - Gargoyle Spaventoso - Scary Sinestro - Scary Diavolo - Devil Vampiro - Vampire Fantasma - Ghost Foletto - Goblin Mostro - Monster Lunu Mannaro - Werewolf Frankenstein - Frankenstein Zombie - Zombie Mummia - Mummy Casa Infestata - Haunted House Zucca - Pumpkin Jack-o-Lantern - Jack-o-Lantern Costume di Halloween - Halloween Costume Dolcetto o Scherzetto - Trick or Treat Morti - The Dead The Physical Closeness of the Italian People One of the most obvious cultural events a visitor to virtually any town or village in Italy notices is a simple one: la passeggiata--the evening stroll. This isn't really an event. It's a cultural, daily habit of the Italian people. Instead of staying in each evening, families, friends and neighbors venture out and stroll together in the largest viale, piazza or strade principali. They stroll for social reasons. To be seen and to see. To stop with neighbors and listen to the latest political news or local gossip. They dress their best, as is the custom of la bella figura. They show off their new clothes, shoes or hairdos. They will see how pregnancies are progressing and show off how well the bambini are growing and flaunt their new puppy. Young teens fare la civetta (make like an owl, or flirt) and older singles check out who is available and perhaps meet up for an aperitivo in a street side cafe or some gelati. Both men and women will stroll arm in arm. When neighbors and cousins or school friends meet, they embrace and kiss, not once, but twice on both cheeks. They talk with their hands, often very excitedly, waving arms and making both subtle and dramatic arm and hand movements, oven combined with facial expressions or huffs and puffs. This is the language that runs the length of the boot from North to South. The Morning Ritual Each morning, millions of Italians have their breakfast standing up, shoulder-to-shoulder in local bars. The bar in Italy is not what you think. While they do serve a certain amount of wines and spirits, they are the place where Italians have breakfast: espresso and a sweet bread or tart, the most popular being a the crescent shaped cornetto. They have tarts, cakes, breads, and even sandwiches or pizza for lunch. They sip their strong espresso or cappuccino and have a morning snack while reading the paper or chatting with neighbors or work-mates. This is a social event at the beginning of each day. Long Lunches at Home Most Italians don't have lunch in restaurants. Most simply prefer to go home for riposa, that 3 hour lunch period from 12 noon until 3pm. Traditionally, pranzo (lunch) is considered the most important meal of the day. Even if they wanted to go to a restaurant for lunch, unless they are in a large city, like Rome or Florence, restaurants are also closed at noon. Italians prefer to spend the hot midday with close family at home and prepare hearty meals, and resting before returning to work. This affords even more hours that la famiglia spend together in close quarters... unlike Americans, who barely eat dinner together at the dinner table. Closeness of la Famiglia Another type of closeness is la famiglia itself. Although the average number of children Italians have is two, la famiglia living in one house or apartment are larger than you might assume. Aging family members in Italy are usually taken care of by younger generations, with sometimes as many as three generations living together in the same house--Nonna and Nonno, Mama and papà, i bambini and sometimes even an aunt or uncle or two. On weekends, extended families get together for pranzo di Domenica (Sunday lunch), either at a relative's home or a local agriturismo. When they eat outside the home, they all gather at long, family style tables, often seating 15-20. Often the meals are communal, served up in large trays or bowls, portions spooned out as needed. On some special holidays, such as during Natale, communal recipes like Polenta alla Spianatora is served on a bread board, with family members scraping polenta and sausages directly from the large board with their own forks. Crowded Sagre, Festivals and Events All throughout the year, regardless of season or region, there are literally thousands of festivals and sagre (food themed festivals) in Italy. Some estimates put the number of sagre at over 42,000! There are celebrations for nearly every type of cheese, wine, nut, berry, meat and pretty much everything else that can be grown and turned into something to eat, and nearly every type of animal: almonds, prosciutto, oranges, wild boars, donkeys, horses, Grappa, bread, pasta, chocolate, olives, fish... you name it, and there's probably a sagra to celebrate. As in the photo above, many events employ long family style tables for friends and strangers to dine together in the streets.  The crowds at the Siena Palio The crowds at the Siena Palio Then there are thousands of events like the Palio in Siena, that insane bareback horse race where 17 neighborhoods compete. Over 40,000 people jam pack into the Campo to experience this race. Then each contrada (neighborhood) have communal dinners for thousands on the streets. Take this one event and multiply by literally thousands... all over Italy, Sicily and Sardinia. People communing together, shoulder to shoulder. Living, loving, eating, drinking, dancing, soaking in la Vita Bella. Imagine how crowded the Venice and Viareggion carnevale are each year. Now picture the seasonal markets. And the New Year's Eve crowds and rock concerts. Over 60 million Italians crushing, standing, chanting, singing, eating, marching... tutti insieme (all together). Italy Has a Vulnerable Elder Population In fact, Italy has nearly 20,000 people over 100 years old and has held the worlds record for the oldest living human nearly every year for the last couple of decades. Italy also has the second highest life expectancy in the world, too--at 83 years young. The reasons for this aging population are varied. The Mediterranean diet, hills and steps keep people in general good health. People tend to retire earlier, giving a more relaxed, stress free lifestyle to the elderly. The midday riposa offers a way the oldest family members can still share in a meal and visits with younger family members, which we all know provides a healthy family environment. They often live with their children and play and hug their grandchildren, who we now realize might carry the COVID-19 virus without symptoms and pass it on to the older family members. Without the stress of how older people are going to have health care (there is national healthcare in Italy), Italians feel comfort in knowing that if something bad happens to their health, they will be taken care of, for little or no cost. The one factor that might actually make the aging population more vulnerable to COVID-19 is the fact that many still smoke. There are far too many smokers in Italy in all age groups. COVID-19 does well in patients with compromised lungs. But of course, people living to healthy old age is not the reason why many might succumb if they contract the disease. This virus is different and powerfully and quickly attacks the vulnerable. We should applaud the Italians living to ripe old ages, if only that they made it in a vivacious, healthy way. They often live with their children and play and hug their grandchildren, who we now realize might carry the COVID-19 virus without even knowing. Ferragosto, the National Vacation Then there's vacation time. Italians don't stagger their summer vacations over three months like Americans. Most of Italy shuts down for Ferragosto in August, the month-long holiday season when Italians head for their campers or beach bungalows and crowd the beaches along its 4,723 miles of coastline. They literally pack the beaches and campsites or head up into the cooler mountains. During summer, there are thousands and thousands of major and minor concerts from the Veneto to Tuscany to Campania and Puglia. Indoor concerts, outdoor concerts, music festivals in rock, folk, opera, jazz... you name the music, there's a festival to suit any Italian's musical tastes. Can the Spread of COVID-19 be Really Blamed on the Culture?

I would argue, no. How can anyone blame a culture for doing what comes naturally? Italians are gregarious. They have close knit families. They love to hold festivals for just about anything God has graced their land with. They hug and kiss and walk arm-in-arm. COVID-19 has taken all of this away from them--at least for now. But you can see the evidence of of Italians sharing even this in a joyful way by banging pots and pans on their balconies... and by making music with all sorts of instruments, again, from their windows or balconies. They sing Bella Ciao together as the WWI partisans did several generations before. They sing their national anthem. They light candles. Even though they are apart, they are together in wearing masks and gloves and battling this unseen enemy, as they have done in the past for thousands of years. They are partisans. The closeness of Italians is not to blame. The emotional closeness and comraderie of the Italian people are the cure for what is ailing them. Andrà Tutto Bene --Jerry Finzi  On the 6th of January every year, La Befana, the Italian witch, delivers treats to children across Italy, just as Babbo Natale does on Christmas Eve. But la Befana is a witch (albeit, a good one) who travels by broom, magically swishing down chimneys and leaving presents in children's pillow cases, stockings and shoes. In her hometown of Urbania--in the region of Marche--50,000 Italians celebrate this good witch's arrival with literally tons of desserts and foods. Throughout the streets and piazzas, you will find theater performances, fire-eaters, la Befana on stilts and also be amazed when she flies overhead (on a cable). The Festa Nazionale della Befana gives an alternative insight of holiday celebrations... it's perhaps one of the best festivals of the holiday season. --GVI Click on the photo above to watch a video of this festival

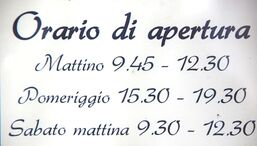

"Orario" means "hours" "Orario" means "hours" Most Italians work long hours. In the average business, their weekday hours are 9.00 am (9:00) to 1.00 pm (13:00) and from 2.30 pm (14:30) to 6.00 pm (18:00), from Monday to Friday. They use the 24 hour military clock. Many people will work well after 6.00 pm, especially true for managers and entrepreneurs. This is one of the reasons they take long lunches--called riposa--typically from 1 pm until 3 - 3:30 pm. Even most churches are closed from noon until 3 pm. There are many jobs which have their workers come in from Monday through Saturday, but they only work from 8.00 am to 2.00 pm. When a business is closed on Saturday, they might also add a few afternoon hours for their employees. According to Italian labor laws, the number of hours worked in a week can reach a maximum of 40. The average time, including overtime, cannot exceed 48 hours. Workers in Italy are guaranteed a minimum of 4 weeks paid days off for vacation and holidays. Some unions negotiate even longer periods of paid vacation/holiday days off. Lunch breaks are typically shorter in large cities and restaurants are open during the lunch hours. In smaller towns, even restaurants will be closed during riposa because most people prefer to eat at home. (But food is available at "bars", which are open). In almost all cases, many shops, even in large cities, will be closed for riposa with their hours listed on the door. In addition, during the August holiday season of Ferragosto, when workers take from 2-4 weeks off for holiday, you might see a sign on shop or restaurant doors saying "Chiuso Per Ferie" (Closed for Vacation) with a date when they will return from vacation. Most Italians take a two week vacation (called Ferragosto on August 15th) either before or after August 15th. Most large industries are closed during August and many museums and restaurants might also be closed. Many people take the entire month to rest and relax before returning to work and school on September 4th. The other period of time when holidays might affect normal business hours is the period between Christmas, New Year's Day and the Epiphany on January 6. Since Italy is a Catholic country, many national holidays coincide with religious holidays.

In addition, all Italian cities celebrate the patron saint as a legal holiday. All businesses are closed on...

Procession in Itri, Lazio leading their way toward the bonfire Procession in Itri, Lazio leading their way toward the bonfire In Puglia, Basilicata, Lazio, Umbria, Lombardy and other regions of Italy, many towns and villages celebrate la Festa di San Giuseppe (March 19th) in a unique way... by lighting Fuochi nella Notte, fires of the night--or bonfires. The bonfires and festivities are on various days (depending on the town), from March 17th through the 19th. Known by different names, the bonfire festival might also contain the words Torciata (torch), Fiaccolata (torchlight procession), Falò (fire). For example, in Tuscany's Pitigliano, the event is called Torchiata di San Giuseppe with people dressed in medieval costumes and a procession of men and boys dressed in hooded monk's robes carrying flaming reed torches that will help build the bonfire. After the bonfire has burned down to ashes, tradition calls for people to collect and keep the ashes, ensuring their good luck in the coming spring. As with other holidays beginning in the New Year and throughout lent, the lighting of bonfires has a long history going back to the time of pagan worship. Through the last 2000 years, the activity has morphed into a Christian tradition. This tradition also coincides with the need to burn the trimmings from vines, olive trees and other woody crops. While Christians claim the fires are a representation of the good father, Saint Joseph, striving to keep the infant Jesus warm during winter nights, others say the tradition is from the ancient Romans celebrating the dark winter being overtaken by the light of spring. Many modern observers say it's just another way for fun-loving Italians to throw yet another party, for as with most festa and sagre, there is always the food, and a great sense of community.

And if the truth is to be told, Italians love bonfires so much, you will also come across other Fuochi on other saint day festivals across Italy. --GVI Today, March 8th, is International Women's Day and in Italy it's the time when mimosas are blossoming with their golden color. All across Italy women are presented lovingly with a bouquet of mimosa flowers to say "Thank you"... thank you for being Mama, that you for being my sister, thank you for being a great daughter, thank you for being a fantastic co-worker, or thank you for being a wonderful wife. March 8th is called La Festa delle Donne in Italy. While in Italy the day has become almost like Mother's Day here in the States, the observance started in 1909 by the Socialist Party of America, and was held in New York City after a sweat shop factory burned to the ground, killing 145 workers--mostly young women who were underpaid and had to work in unsafe conditions. This event and the observance was the de facto birth of the modern Women's Movement. Sadly, in Italy and around the world, women are still struggling to achieve equal pay for equal work, among many other issues. The tradition of a gift of mimosas dates back to 1946 when the feminists, Rita Montagnana and Teresa Mattei, came up with the idea of women offering the bouquets as a symbol of mutual respect, sisterhood and support. Mimosa was one of the few flowers in bloom on the date. The Mimosa also represents strength and endurance, being a tough plant that can survive adverse conditions in Italy. Oddly, being originally a Socialist observance, it seems that in Italy, the Festa delle Donne has been commercialized... another day where bouquets of Mimosa tied with yellow ribbons are sold in supermarkets, bars and tobacconists all over Italy. It's become expected that fathers, sons and husbands also give the flowers to the women in their lives. The commercialization of La Festa delle Donne has made it more like Mothers Day and might be losing some of its original meaning based on solidarity of women's issues. Even chocolate companies offer their dolci in yellow packaging. In some parts of Italy the Festa is celebrated on the closest Sunday to March 8th, and special events are held, such as a procession of mimosa decorated gondolas in Venice and a regatta for female rowers. . --GVI The commercialization of the Women's Movement in Italy From Grand Voyage Italy to all Women... Auguri!

Support each other and keep up the fight for equality!  And then there were three. My brother Kenneth and the twins with Mom and Dad. And then there were three. My brother Kenneth and the twins with Mom and Dad. I suppose the first gift to my father, Sal, was his first two children... the "Twins", Joan and Barbara, born three days apart but healthy, nonetheless. This was the start of my immigrant Dad's entry into fatherhood. Just when other men were being drafted into the U.S. army to fight in World War II, he suddenly was burdened not with one, but two children--this was in 1942 when twins were a mere 1% of all births. His nickname, Sally-Boy was coming to an end. Things had just gotten serious. When he saw only one baby on that first day, the doctor casually told him, "The second one just isn't ready yet". He couldn't rest assured that everything was OK until the second was born three days later, an event that placed my mother's photo holding the two of them on the pages of New York City's Daily News. The war started and my Dad worked in a defense plant making springs for tanks. As you can see from the photo above, my father was not only a proud father, but a rather goofy one. Always the joker... that was his first real gift to his children. John and Barbara were to be followed by Kenneth, Joyce-Ann and myself, the "baby" of the brood. Somehow, Dad provided. Before he was married, he and his brother had a "Three Legged Horse and Cart" and sold fruit and vegetables to the seamen down at Hoboken harbor. He had dreams of having his own Italian delicatessen or market someday, but he opted to have security for his family, always working for others for a steady salary. He clothed and fed us by being a grocery and deli man his entire life. This was another gift to us all.  Always the clown, even as a young man Always the clown, even as a young man Dad always played the fool, constantly at the ready to play a joke on us, to get us to laugh, putting us close to sheer embarrassment. At the beach he always insisted that we bury him under the sand, head exposed with his shoes stuck out 12' away from his head under a ridiculously long body of sand. Everyone passing by loved it. After a while (and his nap) we'd mockingly wind up stomping on his sandy "stomach" (safely clear of his real one) to the amusement of others around us, aside from my mother, who always made like she didn't know him. When we were the only Italian family going to a New Jersey mountain lake previously only frequented by Germans, my father offered them meatballs, sausage and spaghetti and became the biggest clown in the middle of the lake, making his infamous sea monster growl that echoed from the mountainside. He taught us to put small, rounded stream stones into the barbecue so they would explode and scare the heck out of Mom when she was grilling burgers and hot dogs. He came up with the idea to put the watermelon in the stream to keep it cool all afternoon--which worked great except for one day when my sister and I had to run, splashing down the stream to recapture it after it got loose. These were also gifts from Dad. Dad always took me fishing and crabbing down the abandoned docks and piers along the Hudson River. He taught me how to get past chain link fences and avoid guard houses to find the best fishing spot. I remember long, hot afternoons, the smell of fish and tar, and the pinching of the crabs we'd catch in our box crab nets. Some days we'd be there so long until the tide shifted on the Hudson... in the morning the river would be flowing out to sea, and in the afternoon it the river would actually flow upstream. He'd also drop some bait lines from the wooden pilings using little screw-in springs with bells on them. A big "Mama eel" would latch on to a hook, the bell would ring and Dad would have dinner for him and Mom. One day we caught a big eel in the crab net and a big Jersey blue crab on the drop line. At the end of a long day, we'd head home with a bucket full of beautiful blue crabs and perhaps a few eels to fry up. Again, more gifts from Dad. Of course, we all bought Dad gifts for Father's Day. I remember saving the deposit money I earned from collecting empty soda bottles and buying him a bottle of shaving lotion or a pair of socks. A I got older, my gifts were many and varied: bottles of Amaretto, a fishing rod, a lop-eared rabbit, a 3 foot tall basket woven bottle of Chianti, a turquoise pocket knife, a trip to Caesar's Palace in Atlantic City, and odd assortments of power and garden tools.

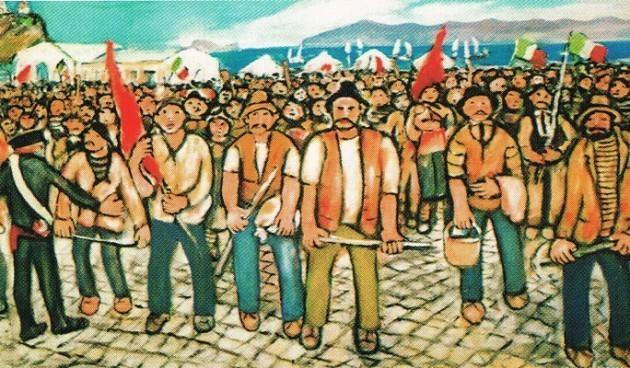

But looking back, my gifts never matched the gifts he gave to me. He gave rock-solid, undeniable love and pride toward me. He gave simple, sound advice when I most needed it. He even gave me the gift of my wife and son when one day challenging me, "So, when are you going to marry that girl? You spend all your time with her anyway!" Thanks Dad... for everything. --Jerry Finzi  In the United States, May Day isn't really a holiday at all. All we know about it is when people with roots from Germanic countries celebrate the return of summer with children dancing around the ribboned May Pole. We also know it as a day of marches for left-wing or worker political parties promoting their agendas for various worker's rights, similar to how workers in many countries treat May Day. In Italy, the 1st of May is called Festa dei Lavoratori (Workers' Day), similar to American's Memorial Day or Labor Day. While there might still be workers marching and holding protests depending on which way the the political and economic wind is blowing, for most workaday furbo Italians, it's simply a day off from work and a long weekend to go to the beach, attend one of the many rock concerts, have a barbecue or rent a holiday cabin in the mountains. After all, it's a lot of work to organize and protest on hot city streets, isn't it? Easier to just go to the beach and throw some steaks on the grill. Most museums are closed as well as many other shops for the entire holiday weekend. This is perhaps not the best weekend to visit major tourist destinations in Italy simply because this is one of the holiday weekends where Italians do the tourist thing... just the way Americans might visit tourist sites in the States during Memorial Day or Labor Day weekends.  Red flag raised on maypole at Appignano del Tronto Red flag raised on maypole at Appignano del Tronto Still, in some parts of Italy (southern Marche, for example) a red flag is placed at the top of a poplar tree as a Socialist party symbol. If you're overly anti-communist, don't get paranoid... Italian socialists--and communists--mix well with other Italians and tourists alike. You might meet them later on during the weekend at the beach... Have a great May Day! --Jerry Finzi Confraternities of Penitents or Congrèe in Italian, are Roman Catholic religious groups, with bylaws prescribing various penitential works. Beginning in the mid 12th century, a members of these brotherhoods were referred to as converso, Church laymen who had made a "conversion of life" and were affiliated to a monastic order as lay brothers.  Penitents, also called Addolorati, are those who adopted asceticism, of which there are two types. "Natural asceticism" is a lifestyle with lessened material aspects, fasting, refraining from sexual relations without actually entering a monastery. "Unnatural asceticism" includes self infliction of pain or flagellation. These Penitents lived fairly normal lives, while adhering to rules against blasphemy, gambling, drunkenness, and womanizing. In 1227 Pope Gregory IX recognized his "Brothers and Sisters of Penance". As with today, most penitent confraternities were involved in charitable activity and considered benefactors to both Church and their local communities.  In the past as well as today, the penitent brothers are known for wearing robes and pointed hoods during public processions on Catholic holy days, such as Good Friday, to hide their identities, both for purposes of hiding their sinfulness and providing anonymity for their charitable works. I feel it must be pointed out (unintended pun here), that these are good-hearted, devout Catholics. Although their pointed caps and white robes (there are other sects throughout Europe with other colors: black, red, blue, etc.) repulse most Americans, the similar garb worn by the extreme racist members of the Ku Klux Klan and these pious Catholic brotherhoods have absolutely nothing in common with each other. The Klan sides with the Devil... the Penitents with God... --Jerry Finzi Enna, Sicily

|

On AMAZON:

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed