Will Piazza Navona become a lawn? Will Piazza Navona become a lawn? Today, April 22nd is Earth Day's fiftieth anniversary. In Italy, Earth Day is called Villaggio per la Terra (Village for the Earth), along with the philosophy that it does take a village to heal Mother Earth. As we humans are battling the COVID-19 virus, we find the opposite with Mother Nature... she is healing herself while we all stay at home, stop driving our vehicles and factories and businesses slow to a halt. We are using gasoline at such low levels that this week crude oil prices were became literally worthless--trading prices went under one cent per barrel! The air has 45% less carbon emissions since our world-wide stay-at-home began. Rivers and the sea are looking cleaner, evidenced by the canals and lagoon of Venice suddenly becoming clear, with jellyfish and dolphins swimming around. Wild boars and goats roam the streets of Italian towns. All over Italy you can see the change--Nature taking over. In the empty Piazza Navona, grass has even started growing! And perhaps the waters of Venice are a bit clearer considering the usual number of 30,000 tourists a day dumped onto its islands are gone and not using the toilets, which in many cases, drain directly into the canals. Cruise ships alone release over one billion gallons of sewage into the ocean every year! And for now, at least, they've stopped. Will there be lessons learned from less driving, less cruise ships and less tourists all battling to occupy the same "must see" spots in Italy and around the world? Time will tell... Happy Earth Day, tutti! --Jerry Finzi Watch the video below to see how the air pollution over Italy and Europe has lessened during the COVID-19 shutdown.... The Physical Closeness of the Italian People One of the most obvious cultural events a visitor to virtually any town or village in Italy notices is a simple one: la passeggiata--the evening stroll. This isn't really an event. It's a cultural, daily habit of the Italian people. Instead of staying in each evening, families, friends and neighbors venture out and stroll together in the largest viale, piazza or strade principali. They stroll for social reasons. To be seen and to see. To stop with neighbors and listen to the latest political news or local gossip. They dress their best, as is the custom of la bella figura. They show off their new clothes, shoes or hairdos. They will see how pregnancies are progressing and show off how well the bambini are growing and flaunt their new puppy. Young teens fare la civetta (make like an owl, or flirt) and older singles check out who is available and perhaps meet up for an aperitivo in a street side cafe or some gelati. Both men and women will stroll arm in arm. When neighbors and cousins or school friends meet, they embrace and kiss, not once, but twice on both cheeks. They talk with their hands, often very excitedly, waving arms and making both subtle and dramatic arm and hand movements, oven combined with facial expressions or huffs and puffs. This is the language that runs the length of the boot from North to South. The Morning Ritual Each morning, millions of Italians have their breakfast standing up, shoulder-to-shoulder in local bars. The bar in Italy is not what you think. While they do serve a certain amount of wines and spirits, they are the place where Italians have breakfast: espresso and a sweet bread or tart, the most popular being a the crescent shaped cornetto. They have tarts, cakes, breads, and even sandwiches or pizza for lunch. They sip their strong espresso or cappuccino and have a morning snack while reading the paper or chatting with neighbors or work-mates. This is a social event at the beginning of each day. Long Lunches at Home Most Italians don't have lunch in restaurants. Most simply prefer to go home for riposa, that 3 hour lunch period from 12 noon until 3pm. Traditionally, pranzo (lunch) is considered the most important meal of the day. Even if they wanted to go to a restaurant for lunch, unless they are in a large city, like Rome or Florence, restaurants are also closed at noon. Italians prefer to spend the hot midday with close family at home and prepare hearty meals, and resting before returning to work. This affords even more hours that la famiglia spend together in close quarters... unlike Americans, who barely eat dinner together at the dinner table. Closeness of la Famiglia Another type of closeness is la famiglia itself. Although the average number of children Italians have is two, la famiglia living in one house or apartment are larger than you might assume. Aging family members in Italy are usually taken care of by younger generations, with sometimes as many as three generations living together in the same house--Nonna and Nonno, Mama and papà, i bambini and sometimes even an aunt or uncle or two. On weekends, extended families get together for pranzo di Domenica (Sunday lunch), either at a relative's home or a local agriturismo. When they eat outside the home, they all gather at long, family style tables, often seating 15-20. Often the meals are communal, served up in large trays or bowls, portions spooned out as needed. On some special holidays, such as during Natale, communal recipes like Polenta alla Spianatora is served on a bread board, with family members scraping polenta and sausages directly from the large board with their own forks. Crowded Sagre, Festivals and Events All throughout the year, regardless of season or region, there are literally thousands of festivals and sagre (food themed festivals) in Italy. Some estimates put the number of sagre at over 42,000! There are celebrations for nearly every type of cheese, wine, nut, berry, meat and pretty much everything else that can be grown and turned into something to eat, and nearly every type of animal: almonds, prosciutto, oranges, wild boars, donkeys, horses, Grappa, bread, pasta, chocolate, olives, fish... you name it, and there's probably a sagra to celebrate. As in the photo above, many events employ long family style tables for friends and strangers to dine together in the streets.  The crowds at the Siena Palio The crowds at the Siena Palio Then there are thousands of events like the Palio in Siena, that insane bareback horse race where 17 neighborhoods compete. Over 40,000 people jam pack into the Campo to experience this race. Then each contrada (neighborhood) have communal dinners for thousands on the streets. Take this one event and multiply by literally thousands... all over Italy, Sicily and Sardinia. People communing together, shoulder to shoulder. Living, loving, eating, drinking, dancing, soaking in la Vita Bella. Imagine how crowded the Venice and Viareggion carnevale are each year. Now picture the seasonal markets. And the New Year's Eve crowds and rock concerts. Over 60 million Italians crushing, standing, chanting, singing, eating, marching... tutti insieme (all together). Italy Has a Vulnerable Elder Population In fact, Italy has nearly 20,000 people over 100 years old and has held the worlds record for the oldest living human nearly every year for the last couple of decades. Italy also has the second highest life expectancy in the world, too--at 83 years young. The reasons for this aging population are varied. The Mediterranean diet, hills and steps keep people in general good health. People tend to retire earlier, giving a more relaxed, stress free lifestyle to the elderly. The midday riposa offers a way the oldest family members can still share in a meal and visits with younger family members, which we all know provides a healthy family environment. They often live with their children and play and hug their grandchildren, who we now realize might carry the COVID-19 virus without symptoms and pass it on to the older family members. Without the stress of how older people are going to have health care (there is national healthcare in Italy), Italians feel comfort in knowing that if something bad happens to their health, they will be taken care of, for little or no cost. The one factor that might actually make the aging population more vulnerable to COVID-19 is the fact that many still smoke. There are far too many smokers in Italy in all age groups. COVID-19 does well in patients with compromised lungs. But of course, people living to healthy old age is not the reason why many might succumb if they contract the disease. This virus is different and powerfully and quickly attacks the vulnerable. We should applaud the Italians living to ripe old ages, if only that they made it in a vivacious, healthy way. They often live with their children and play and hug their grandchildren, who we now realize might carry the COVID-19 virus without even knowing. Ferragosto, the National Vacation Then there's vacation time. Italians don't stagger their summer vacations over three months like Americans. Most of Italy shuts down for Ferragosto in August, the month-long holiday season when Italians head for their campers or beach bungalows and crowd the beaches along its 4,723 miles of coastline. They literally pack the beaches and campsites or head up into the cooler mountains. During summer, there are thousands and thousands of major and minor concerts from the Veneto to Tuscany to Campania and Puglia. Indoor concerts, outdoor concerts, music festivals in rock, folk, opera, jazz... you name the music, there's a festival to suit any Italian's musical tastes. Can the Spread of COVID-19 be Really Blamed on the Culture?

I would argue, no. How can anyone blame a culture for doing what comes naturally? Italians are gregarious. They have close knit families. They love to hold festivals for just about anything God has graced their land with. They hug and kiss and walk arm-in-arm. COVID-19 has taken all of this away from them--at least for now. But you can see the evidence of of Italians sharing even this in a joyful way by banging pots and pans on their balconies... and by making music with all sorts of instruments, again, from their windows or balconies. They sing Bella Ciao together as the WWI partisans did several generations before. They sing their national anthem. They light candles. Even though they are apart, they are together in wearing masks and gloves and battling this unseen enemy, as they have done in the past for thousands of years. They are partisans. The closeness of Italians is not to blame. The emotional closeness and comraderie of the Italian people are the cure for what is ailing them. Andrà Tutto Bene --Jerry Finzi Yesterday, Pope Francis preached to an empty piazza in front of Saint Peter's basilica in Rome... "For weeks it seems that evening has fallen. Dense darkness has thickened on our squares, streets and cities; they took over our lives and we found ourselves afraid and lost, taken aback by an unexpected and furious storm. We realized that we were on the same boat, all fragile and disoriented, but at the same time important and necessary, all called to row together."

When I started the Facebook Group Garden of the Finzi Famiglia, its intent was to bring together the multitude of people in the world with the Finzi surname. In the beginning, it was a way for me to search for my actual genetic roots and perhaps meet some long lost cousins along the way. Among our 225 active members, all named Finzi (or a variant), I have succeeded in finding my Catholic, Finzi cousins with whom I share a common DNA, all originating from the town of Molfetta, Puglia where my father was born. But there are other, larger branches of what I call la Famiglia Finzi, many whom are Jewish, and can trace their heritage back to the time of the Medici in Northern Italy. Although my small branch is special to me because we are related by blood, I also feel like a "cousin" to all of the many hundreds of Finzi that I have become online friends with, from Italy to England, Brazil and Argentina, the U.S. and France, Norway, Tunisia and beyond. Through our Garden group, we have all found commonalities and feel like extended cousins.  But the reason I am writing this post is to celebrate the life and passing of one particular Finzi... Doctor Giuseppe Finzi, professor of vascular diseases and head of the Day Hospital at the University of Parma. Beppe, as his friends called him, was also author of over 60 publications in national and international scientific journals, was a member of the Italian Society of Internal Medicine and was very active in Italian politics. This past Wednesday, we lost Giuseppe as he was fighting on the front lines of the coronavirus Italian crisis. His underlying health issues made him an easier target for the terrible coronavirus, taking him only a few days after he was first diagnosed. We mourn this amazing Finzi. He held the name proudly and was actually able to trace his family tree back 1000 years. He was one of a long line of doctors, rabbi and teachers throughout the history of this noble Jewish Finzi family line.  Giuseppe and Daughter Giuseppe and Daughter His humor, smile and hugely generous personality was loved by thousands who knew him. He was a perpetual volunteer for charitable programs, a sailor, a chef, a dog lover, a sun-worshiper, a passionate soccer fan, and one-time candidate for mayor of Soragna, his home town. One of his recent pet projects was a healthy cooking program for at-risk young women where he enjoyed donning the chef's toque and jacket. His passing brings the number of Italian doctors lost during this crisis up to 13. Giuseppe Finzi was 62 when he passed. Our condolences to his family and wife of three years, Daniela. --Jerry, Lisa and Lucas Finzi "Not only did he participate in every activity, but he always found a way to make himself useful", says Riccardo Moretti, president of the Jewish Community of Parma. "A pure person, a friendly face that all of us will miss."

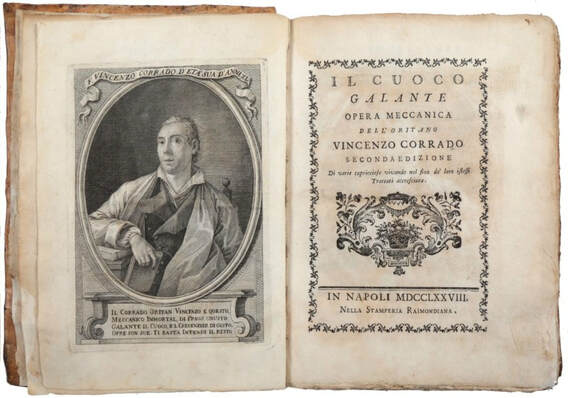

One of the more intriguing aspects of the Venice Carnevale is the beautifully fantastic cartapesta masks attendants wear. Many are colorful, feathery, glittered and elegant. But there is one long, bird-beaked mask that can creep out most who come across it... the Medico della Peste or Dottore Peste (plague doctor). This birdlike mask wasn't originally designed for the pleasures of Carnevale, but in fact was was invented in the 17th century by French physician Charles de Lorme to protect doctors airborne bacteria and viruses while treating victims of the plague. Carnival goers eventually started wearing a decorated version called Memento Mori, to remind them of their own mortality. In the 1600s, the beak was to be filled with aromatic and medicinal herbs to protect them from putrid air, which at that time was seen as the cause of infection. Often the city or town paid their fees, and some plague doctors were known to charge patients and their families (especially the wealthy) additional fees for special treatments for false cures. These so called "doctors" were often lay people without medical training, their only apparent useful purpose was in detailing and recording how many of the population were actually affected by plague. Even though these plague doctors offered little real healing, their value to the ruling class and local governments were overly inflated. In Florence and Perugia, doctors were often asked by officials to perform autopsies to help determine how the plague played a role. The city of Orvieto hired plague doctor Matteo fu Angelo in 1348 for four times the normal annual rate of a traditional doctor. Pope Clement VI hired several extra plague doctors during the Black Death to attend to stricken in Avignon. Of 18 doctors in Venice, only one was left by 1348: five had died of the plague, and 12 were missing and may have fled. Their special costume were first used in 1630 in Naples, and spread to be used throughout Europe. The spooky attire consisted of a light, waxed fabric overcoat, a mask with glass goggles and that frightening beak. They carried a scalpel for cutting open blisters (the goggles protected their eyes from the spatter) The wide brimmed hat identified most doctors during this time. Around their neck they wore a pomander which contained more herbs and aromatics--again, to protect themselves. They also kept and chewed raw garlic whenever near the inflicted. Their long cloak went nearly to the ground and was waxed heavily to ward off damp and fleas--possible carriers of the disease. They also carried a long cane to poke and probe patients during examinations and treatments, to avoid actually touching them. As mentioned earlier, that beak was stuffed with herbs, straw, and spices. The scented materials included juniper berry, ambergris, rose hips, mint, camphor, cloves, laudanum and myrrh.

Historic facts prove that these charlatans in their scary costumes did little to heal or prevent the plague in Italy. The Italian Plague of 1629–1631 was a series of outbreaks of bubonic plague which ravaged northern and central Italy. This epidemic claimed possibly one million lives, or about 25% of the population in these regions. Verona lost over 60% of its citizens. Milan lost 46%. In Venice, one third died. Stay healthy, amici. --Jerry Finzi Bergoglio is a common Italian surname from the Piedemont region of Italy, although in this case, this man is called Jorge (Giorgio, in Italian) and he was born in Argentina. Yes, that Jorge Bergoglio, also known as Pope Francis. In the last few months, there has been a uprising and controversy when a video went viral--of Pope Francis pulling his ringed hand away from people as he meets. People are angry because HE isn't showing any respect for the Church or its traditions. The video that caused this controversy was from video footage of meeting of pilgrims after the Pope celebrated Mass in the Holy House in Loreto, Italy, on March 25, 2019. In this short video, Pope Francis appears to pull his hand away each time a person approaches to greet him and kiss his hand or ring. But this video didn't exactly show everything that happened that day. In fact, when approached by nuns, in every instance, he allowed them to kiss his hand or ring. But, when it came to the lay people that day, he pulled his hand away from each... (Watch the complete video on this page) Baciamano The custom of kissing the ring of the pope or a bishop has been a gesture of respect in the Church for longer than can be remembered, but likely started in the late Middle Ages. In fact, when I was a child, I remember having to kiss our bishop's ring whenever he visited our church. This ring-kissing is called baciamano (in Italian, literally "hand kiss”), but in practice it refers to kissing the ring worn by any bishop, but especially the Papal Ring of the Fisherman worn by every Pope. Each Pope chooses, designs or selects his own ring to wear during his Papacy. The Fisherman’s Ring is one of several rings typically worn by the Roman pontiff. The ring takes its name from its image of St. Peter as a fisherman, which became the standard design around the mid-15th century. The first record of the ring’s use was on two letters of Clement IV in 1265 and 1266, used as a wax seal in private letters in place of the official lead seal used for solemn papal documents. In 1842, use of the ring and wax seal were replaced by a stamp, but each Pope still receives a unique Ring of the Fisherman at the start of his papacy, which is then destroyed soon after his death. Pope Francis doesn't always wear the Papal Ring, and while outside of official Papal ceremonies, Francis is typically seen wearing only his episcopal ring. It is customary to kiss the ring of any bishop, and being that the Pope also holds the title of Bishop of Rome, he is also technically a Bishop. Kissing a Bishop's ring is done out of reverence for his dignity as a successor of the apostles, and the hand of a priest, as it has been anointed with chrism to consecrate the Body of Christ. The custom of baciamano started to change with St. Paul VI in the last decades of the 20th century, when he eliminated other forms of showing Papal obedience and subservience, such as kissing the pope’s foot, shoulder, and cheek. Kissing the Pope's ring was starting to fall from favor. In the past, one typically bowed while kissing the ring, but in later years, the bowing has also started to disappear.

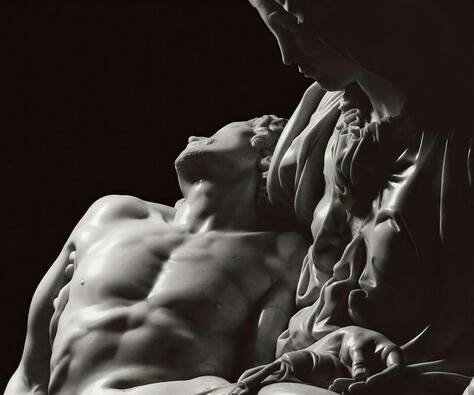

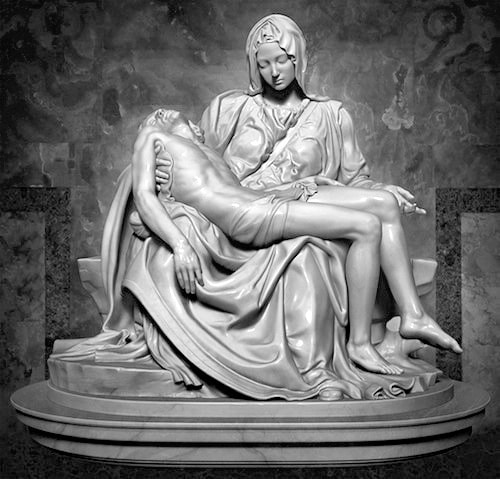

Some Vatican insiders claim that Francis retreats from traditional Vatican Court Customs, wanting to further simplify the ceremonial by omitting the greeting of genuflection and kissing his ring. He sees this as a lessen to the people of his Church that he is also a common man, and only Christ Himself is worth of such respect. He will still allow those "of the cloth", such as nuns and priests to kiss his hand/ring (as is seen in the unedited video of the event in question). He is respecting the internal hierarchy of the Catholic Church in doing this. The Pope is in fact, their leader. But he does not wish everyday people to treat him as if he were some sort of religious idol. He is an "everyman Pope". So he often pulls pack his hand as a lesson for us not to idolize him. Other Reasons for Pulling Back His Hand Still others, point out that the Pope is a senior citizen, and as such, has a weakened immune system. It's prudent to lessen the contact with parishioners, especially during events when the Pope is likely to have thousands try to kiss his hand. Even politicians on their political hand-shaking and baby-kissing campaigns have their aides squirt their palms with Purell after each public event. Anecdotally, I will confess to changing my habits when food shopping when my son was a toddler, riding in the supermarket cart while I shopped. In the first couple of years, it seemed both of us were getting sick a lot... 4-6 times a year we would catch colds. But then I started to use the antiseptic wipes available in supermarkets to wipe down the handle of our shopping cart, and we magically stopped catching colds! I think we can all give the Pope the benefit of doubt on this matter. He is an older man and can catch colds like any other mortal human. He is also a humble Pope and doesn't like being treated like a king or monarch or even the embodiment of the Christ Himself. I think this can be a teachable moment. Use wipes at the supermarket --my lesson. The Pope is just a man, like all others --Francis' lesson. We are all children of God while we are in this mortal form. Germs DO exist and are transferred instantly by touch. There, I've said my piece. Now, does anyone have a Wipe? --Jerry Finzi MICHAEL*AGELUS*BONAROTUS*FLOREN*FACIEBA MICHAELANGELUS BUONARROTI FLORENTINE MADE THIS The Pieta (passion or pity) showing the Holy Mother Mary holding the lifeless body of her son Jesus, is the only sculpture that Michelangelo ever signed--on the sash across Mary's breast. When I first saw the Pieta at the 1963 Worlds Fair in New York, I noticed this signature and can remember thinking, "What a bold place to sign a piece of art"... Michelangelo was only 24 when he sculpted this masterpiece. He was young and proud, perhaps even cocky about his skills. I can relate to this. I left school early, and at 17 got a job as a sculptor's apprentice in a metal sculpting studio that designed churches around the world. I was so cocky about my own skills, I couldn't live with making sculptures to the exacting standards of the blueprints made by our studio's Master Sculptor. I knew I couldn't last long there. My mother always claimed I could draw before I talked, and as a child I dreamed of being a painter and sculptor. Michelangelo was certainly a child prodigy and also dreamed of being an artist. He stuck to his painting and sculpture and by age 21, he had moved to Rome and had already sculpted his first masterpiece, his Bacchus. For me, a cocky artist who knew he didn't want to starve in some garret somewhere in Greenwich Village (there were no future Popes or Medici supporting my artistic future), I turned to a more technical and commercial form of art--photography. At 21 years of age, I had already advanced to be a top photographer in one of the largest commercial photography studios in the country. By 24 I had opened my own photo studio in my Manhattan loft. At 24, Michelangelo had already created his Pieta. Cocky indeed--deservedly so, perhaps. Raw talent feeds this malevolent human trait, especially in youth. With more experience and gaining skills, I learned not to be so cocky (there is always something more to learn, even in later years), but Michelangelo's youthful cockiness and pride in his skills drove him to sign the Pieta in a bold manner... You see, after creating the Pieta, the sculpture was on display in the Chapel of Santa Maria della Febbre where the Sacristy stands today. When visiting his Pieta one day, Michelangelo overheard a group of Lombards critiquing his masterpiece and was enraged when he heard them attribute the work to the "Gubbo di Milano" (Hunchback of Milan), referring to Cristofor Salari, a well known sculptor 15 years his senior. Some say that this attribution lasted for quite some time before Michelangelo reacted, but many historians claim that Michelangelo went to the Pieta the same night with torch and chisels and carved his name on Mary's sash. It's curious that as he matured and gained self-confidence, Michelangelo never felt the need to sign any of his future works. I can identify with this also. It's often enough for the artist's soul just to create the work... to do his craft... to keep creating. The cockiness fades and is replaced with an internal self-confidence. When one examines the details of the Pieta closely, perhaps there is a realization that the youthful cockiness and pride was well deserved. Go slowly as you look at each one of these photos. Consider that Michelangelo has performed some sort of magical alchemy, turning stone into flesh, with the still warm veins of Jesus still containing his blood... --Jerry Finzi Copyright 2019, Jerry Finzi/GrandVoyageItaly.com - All Rights Reserved

Not for reproduction without expressed permission. Maria Giuseppa Robucci, better known as Nonna Peppa in Italy, is currently the oldest living person in Europe. Nonna Peppa has yet another birthday coming up... on March 20th she will turn 116! This centenarian lives today in Apricena, Puglia with her daughter Filomena and her family. She was born in 1903 in nearby Poggio Imperiale where she married farmer Nicola Nargiso and bore five children, nine grandchildren and 16 great-grandchildren. She managed a local bar along with her husband for many years, is very religious and claims to have known Saint Padre Pio personally. For the last few years she holds the title of honorary mayor of Poggio Imperiale, making her the oldest mayor in Italy. Her secret to longevity? Nonna Peppa doesn't drink or smoke. --GVI Today, March 8th, is International Women's Day and in Italy it's the time when mimosas are blossoming with their golden color. All across Italy women are presented lovingly with a bouquet of mimosa flowers to say "Thank you"... thank you for being Mama, that you for being my sister, thank you for being a great daughter, thank you for being a fantastic co-worker, or thank you for being a wonderful wife. March 8th is called La Festa delle Donne in Italy. While in Italy the day has become almost like Mother's Day here in the States, the observance started in 1909 by the Socialist Party of America, and was held in New York City after a sweat shop factory burned to the ground, killing 145 workers--mostly young women who were underpaid and had to work in unsafe conditions. This event and the observance was the de facto birth of the modern Women's Movement. Sadly, in Italy and around the world, women are still struggling to achieve equal pay for equal work, among many other issues. The tradition of a gift of mimosas dates back to 1946 when the feminists, Rita Montagnana and Teresa Mattei, came up with the idea of women offering the bouquets as a symbol of mutual respect, sisterhood and support. Mimosa was one of the few flowers in bloom on the date. The Mimosa also represents strength and endurance, being a tough plant that can survive adverse conditions in Italy. Oddly, being originally a Socialist observance, it seems that in Italy, the Festa delle Donne has been commercialized... another day where bouquets of Mimosa tied with yellow ribbons are sold in supermarkets, bars and tobacconists all over Italy. It's become expected that fathers, sons and husbands also give the flowers to the women in their lives. The commercialization of La Festa delle Donne has made it more like Mothers Day and might be losing some of its original meaning based on solidarity of women's issues. Even chocolate companies offer their dolci in yellow packaging. In some parts of Italy the Festa is celebrated on the closest Sunday to March 8th, and special events are held, such as a procession of mimosa decorated gondolas in Venice and a regatta for female rowers. . --GVI The commercialization of the Women's Movement in Italy From Grand Voyage Italy to all Women... Auguri!

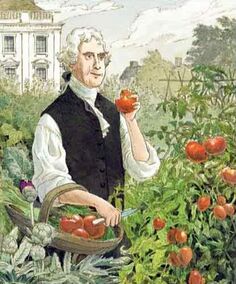

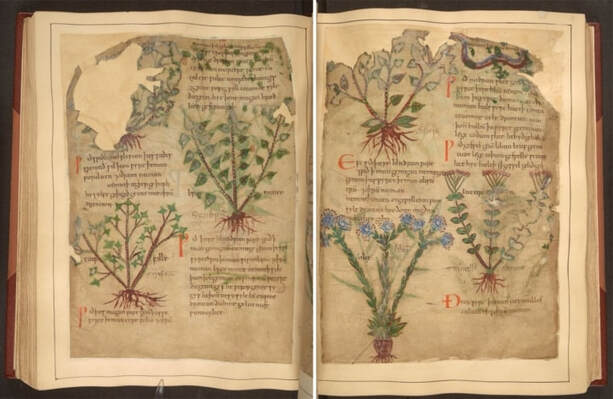

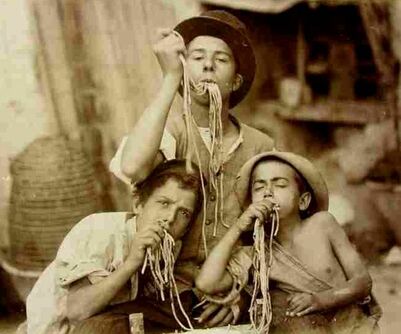

Support each other and keep up the fight for equality!  If you look in my cellar during mid-May of any year, you will find a couple of dozen young tomato plants under my grow light, nearly ready to be planted out in my raised vegetable beds (after fear of frost is gone). My mind always fills with thoughts of tomatoes in this time of year, with hope that there will be a good yield for our little famiglia. If I say, "tomato sauce" you think of Italian food, right? If I say "home grown tomatoes" you might think of Vito Corleone playing with his grandson in his garden in that final scene in his life. If I say "pizza" you picture a round crust with cheese and tomato sauce. That red color emblazoned in the minds and hearts of Italians everywhere (even though heirloom tomatoes come in many colors). Some say that Il Tricolore (the tricolor flag of Italy) represents the hills of Italy with green, the snow capped mountains with white, and the blood spilled from the wars of independence by red. But others in la Cucina Italiana would argue that the green is for pesto, the white for besciamella and the red for salsa pomodoro found in tri-color lasagna... or that the flag represents the simple but wonderful insalata caprese: green for basil, white for mozzarella, and the red for ripe tomatoes. In any case, you might say the red in Il Tricolore represents the true blood of Italy--the tomato.  The Wild Tomato of Peru The Wild Tomato of Peru But how did the tomato become such a strong part of Italian culture? It is not indigenous to Italy, or Europe for that matter. The tomato was first "discovered" by the Spanish Conquistadors while exploring and then conquering the Americas. The Spaniard, Hernán Cortés, conqueror of Mexico in 1519, returned home and brought with him a cargo of Aztec tomatoes. The tomato most likely originated in the Andes mountains of Peru and spread sometime in the distant past to most parts of South and Central America and eventually on up to Mexico. In fact, it was the Incas who first cultivated tomatoes about 1000 years ago, eventually trading seeds to Aztecs and Mayans to the North. Most botanists consider the tiny, scraggly bush Solanum Pimpinellifolium (or "Pimp") as the ancestor of all modern tomatoes, itself becoming an endangered species. The odd thing is that the tomato became popular in Europe long before it came to be used in North America. Colonial Americans thought of the tomato as a poisonous plant, after all, it's a close cousin or Nightshade, a well know toxic vine, and in fact, the leaves and vines of the tomato plant are fairly toxic.  16th century botanical illustration 16th century botanical illustration It was during the 1500s that Columbus and other explorers introduced the tomato to Europe, but 200 years of skepticism had to pass before the tomato gained acceptance there. It was feared that one touch of a tomato on the lips would kill you. One likely catalyst for its popularity in Europe, especially with the wealthy and elite, was the rumor that it was an aphrodisiac. The general population more than likely heard about this new fruit and saw that the Barons and Dukes behind the castle walls were flourishing, not falling down dead. One can imagine that the trash middens where refuse from the castles, chateaus and villas were thrown, became a great source of distribution for the tomato plant. As anyone who grows tomatoes knows, tomatoes are prolific and seeds can spring up anywhere. Leave a fruit on the ground and chances are good you'll have more tomatoes next year. Leave a tomato on the kitchen counter and the seeds might eventually sprout right out of its own skin.  Self-Sprouting Tomato Self-Sprouting Tomato Little by little, the peasants discovered gnarly vines growing wild with attractive red or yellow fruits that were attracting wild life. (Chipmunks love them in my garden!) "Why not give them a try? The birds, squirrels and rabbits aren't dying, after all." Presto... a free, easily grown source of vitamins and amazing flavor. It was easy to save seeds and cultivate a very large harvest from even a modest number of plants. The word tomato is derived from the Aztec word xitomatl, shortened in Europe to tomatl. The French originally called the tomato, pomme d’amour (love apple) before calling simply la tomate. Perhaps they changed the name when the aphrodisiac claims failed to yield any effect. In Italy it was pomi d’oro (golden apple) which today becomes il pomodoro. Tomatoes do come in a wide variety of colors, including golden yellow, but along with tomatoes, the tomatillo also came from the Americas--many of which are also yellow. In Italy, the tomato more than likely prospered because of its near-tropical climate. The tomato can be grown all year long in tropical temperatures. It makes sense the Spanish had tomatoes first, after all, they sponsored the Columbus and Cortes explorations. In this way, Spaniards actually led the way, "teaching" Italians to fry tomatoes up with eggplant, squash and onions, and used the dish as a condiment on bread and with meats. The cuisine of Southern Italian peasants, who often lacked meats and other proteins on a regular basis, developed into a mostly vegetarian diet in which tomatoes and olive oil, spices and vegetables were and eaten with bread, rice or polenta. The first time the pomi d'oro is mentioned by name in Italy was in 1548 in the household records of Cosimo de’Medici, the grand duke of Tuscany. His house steward presented a basket to “their excellencies”. The Duke had no idea what was inside, only that it came from his Florentine estate at Torre del Gallo. The records describe the scene, “And the basket was opened and they looked at one another with much thoughtfulness.” After the event, the house steward wrote to the Medici private secretary to tell him that the basket "arrived safely". But as far back as 1692, tomatoes were used as ingredients in a cookbook from Naples, Lo scalco alla moderna. The author obviously copied details from Spanish tomato sauce recipes ("alla spagnuola"), including simple ingredients like minced tomatoes and chili peppers. Curiously, he did not recommend using the sauce specifically with pasta: "Take a half a dozen tomatoes that are ripe, put them to roast in the embers, when they are scorched, remove the skin diligently, then mince them finely with a knife. Add onions, minced finely, to discretion. Hot chili peppers, also minced finely. Add thyme, in a small amount. After mixing everything together, adjust it with a little salt, oil, and vinegar. It is a very tasty sauce, both for boiled dishes or anything else." Italian nobility at first used this new, jewel-like fruit merely as a tabletop decoration, gradually incorporating it into their cuisine by the late 17th and early 18th century. They cherished their beauty, and experimented with selective breeding, managing to create tomatoes of many colors and shapes  It took another 200 years for the tomato to become the national treasure is it today, but by the late 1700s, the peasants of Naples began to put tomatoes on top of their flat breads, creating something very close to the modern pizza--essentially turning pizzas from white to red. Tomatoes gained popularity, especially with the elite of Europe and Americans taking the Grand Tour, and soon pizza attracted tourists to Naples, tempting them into the poor areas of the city to sample the new treat. Pizza was born. Soon after taking a Grand Tour himself, Thomas Jefferson, being an expert farmer and a culinary expert, brought tomato seeds back from Europe. Jefferson grew tomatoes in his expansive Monticello garden, with his daughters and granddaughters using them in numerous recipes including gumbo, soups, pickling and especially for ketchup (the common use for tomatoes in the 19th century). In an 1824 speech to the Albemarle Agricultural Society, Jefferson’s son-in-law, Thomas Mann Randolph, claimed that ten years before, the tomato was barely known, but by 1824 "everyone was growing and eating them". Slow but sure, people were taking notice of this special fruit.  Pizza Margherita, the birth of modern pizza Pizza Margherita, the birth of modern pizza In the same time period we find the first recorded evidence of tomatoes used in sauces and preserved condiments and pastes. In the 1800s, in Naples a recipe was written about pasta al pomodoro, the very first mention of tomatoes being married to pasta. In 1889, after Italy became one nation, the King and Queen of Italy found it necessary to visit the former kingdom of Naples to appease the citizenry who disliked their loss of independence. Queen Margherita was bored with the same old French cuisine that they were eating everywhere they went--as was the custom in all of Europe. She called for the most famous pizza-maker in Naples, Raffaele Esposito, and commanded that he make pizza for her. He brought three types: pizza marinara with garlic, pizza Napoli with anchovies and a third with tomato sauce, mozzarella and basil leaves. She fell in love with the third one and Esposito named it after her--Pizza Margherita. A short time later, the Queen sent her emissary with a thank you note, which still today hangs on the wall of Pizzeria Brandi, still run by his descendants. Pizza--with tomato sauce--was to become more popular than ever after the Queen's royal recommendation--the equivalent to Royal Yelp nowadays. Emigration to the United States did more to increase the popularity of the tomato than anything else in history. Because of the climate in Italy, tomatoes became a big crop, even small farmers produced an excess of the sweet fruits. A need developed to preserve them, and to create new markets. The only foods that may be safely canned in an ordinary boiling water bath are highly acidic ones--coincidentally, tomatoes are naturally high in acid. Sun drying tomatoes and storing them in olive oil was also a proven way to preserve large stores of tomatoes, as long as no fresh herbs or garlic were added, the method a safe with a long shelf life. During the mid-1800s the science of canning started to develop and improve, allowing this new cash crop to find its way to distant markets. By the end of the 19th century Italians were already using tomatoes in their recipes and as a condiment. When Italians emigrated to America, they wanted to have products that reminded them of home... canned tomatoes filled that need, along with olive oil and other specialty imports. Italians at home and expats in American developed import-export businesses to give relatives and other their compagni jobs based on their new found wealth in America. In Italy, exporting companies were popping up, especially in the Naples area. By the time World War I rolled around, even the Italian Army experimented with canned ravioli, spaghetti alla bolognese and Pasta e fagioli, the inclusion of acidic tomatoes in the recipes aided in the cans' shelf life. Italian grocery stores stocked these products in Little Italy neighborhoods in New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, Boston and New Orleans. Click HERE to read Part 2 |

On AMAZON:

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed