Originally installed in 1874, there are apparently more than 2500 of them... the Nasoni (Big Noses) supply fresh water to the public in Rome. The nickname was given because of their spouts' resemblance to a larger than normal nose. Within the Aurelian walls of Rome there are over 250 of them for your use. And have no fear... this water is perfectly fine for drinking--cold and fresh. In fact, using the nasoni is a great way to save on price gouging that goes on with refreshment street vendors, who charge overly high prices for bottled water. Trust me, it can be very hot and humid in Rome--even in the "cooler" spring and fall. Never go anywhere without a water bottle. Filling your own, reusable sport bottle is the way to do it in Rome. Don't waste money on bottled water.  The nasoni are beautifully designed. The 200 pound, cast iron fountains stand about 3 feet tall, with distinctive spouts supplying a continuous stream of potable water. That's right, it flows all the time. Romans call it l’acqua del sindaco (the mayor’s water), since the government maintains the water flow. The older nasoni have a dragon's head at the end. Newer ones have a smooth torch decoration. Some older ones have three spouts while most have one. Please don't be put off by the rust or minerals built up at the base of the nasoni--the water is perfectly pure. All of the nasoni bear the shield of Rome with SPQR emblazoned on it. This is from the Latin phrase from Ancient Rome: Senātus Populusque Rōmānus (The Roman Senate and People). Today, this is the official emblem of the modern Roman government.  The nasoni also have a little known secret--at least tourists don't seem to know about it... On top of the spout (the nose) there is a small hole that can turn this faucet into a drinking fountain. The trick is holding your hand (hopefully clean) under the open spout, plugging it up. This forces a little water jet to pop out of the small hole on top, allowing you to drink as you would from a modern drinking fountain. (It's customary to rinse your hands before doing this in an effort to keep the spout clean.) Just hold your hand steady as you drink, or you might get sprayed in the face! Watch the cute video below... this bellissima bambina explains it so well. Roman pooches really appreciate lapping up a cool drink Here is a LINK to an interactive map of Rome that can help locate nasoni. There are also over 1000 fontanelle (drinking fountains) scattered around Rome

The Physical Closeness of the Italian People One of the most obvious cultural events a visitor to virtually any town or village in Italy notices is a simple one: la passeggiata--the evening stroll. This isn't really an event. It's a cultural, daily habit of the Italian people. Instead of staying in each evening, families, friends and neighbors venture out and stroll together in the largest viale, piazza or strade principali. They stroll for social reasons. To be seen and to see. To stop with neighbors and listen to the latest political news or local gossip. They dress their best, as is the custom of la bella figura. They show off their new clothes, shoes or hairdos. They will see how pregnancies are progressing and show off how well the bambini are growing and flaunt their new puppy. Young teens fare la civetta (make like an owl, or flirt) and older singles check out who is available and perhaps meet up for an aperitivo in a street side cafe or some gelati. Both men and women will stroll arm in arm. When neighbors and cousins or school friends meet, they embrace and kiss, not once, but twice on both cheeks. They talk with their hands, often very excitedly, waving arms and making both subtle and dramatic arm and hand movements, oven combined with facial expressions or huffs and puffs. This is the language that runs the length of the boot from North to South. The Morning Ritual Each morning, millions of Italians have their breakfast standing up, shoulder-to-shoulder in local bars. The bar in Italy is not what you think. While they do serve a certain amount of wines and spirits, they are the place where Italians have breakfast: espresso and a sweet bread or tart, the most popular being a the crescent shaped cornetto. They have tarts, cakes, breads, and even sandwiches or pizza for lunch. They sip their strong espresso or cappuccino and have a morning snack while reading the paper or chatting with neighbors or work-mates. This is a social event at the beginning of each day. Long Lunches at Home Most Italians don't have lunch in restaurants. Most simply prefer to go home for riposa, that 3 hour lunch period from 12 noon until 3pm. Traditionally, pranzo (lunch) is considered the most important meal of the day. Even if they wanted to go to a restaurant for lunch, unless they are in a large city, like Rome or Florence, restaurants are also closed at noon. Italians prefer to spend the hot midday with close family at home and prepare hearty meals, and resting before returning to work. This affords even more hours that la famiglia spend together in close quarters... unlike Americans, who barely eat dinner together at the dinner table. Closeness of la Famiglia Another type of closeness is la famiglia itself. Although the average number of children Italians have is two, la famiglia living in one house or apartment are larger than you might assume. Aging family members in Italy are usually taken care of by younger generations, with sometimes as many as three generations living together in the same house--Nonna and Nonno, Mama and papà, i bambini and sometimes even an aunt or uncle or two. On weekends, extended families get together for pranzo di Domenica (Sunday lunch), either at a relative's home or a local agriturismo. When they eat outside the home, they all gather at long, family style tables, often seating 15-20. Often the meals are communal, served up in large trays or bowls, portions spooned out as needed. On some special holidays, such as during Natale, communal recipes like Polenta alla Spianatora is served on a bread board, with family members scraping polenta and sausages directly from the large board with their own forks. Crowded Sagre, Festivals and Events All throughout the year, regardless of season or region, there are literally thousands of festivals and sagre (food themed festivals) in Italy. Some estimates put the number of sagre at over 42,000! There are celebrations for nearly every type of cheese, wine, nut, berry, meat and pretty much everything else that can be grown and turned into something to eat, and nearly every type of animal: almonds, prosciutto, oranges, wild boars, donkeys, horses, Grappa, bread, pasta, chocolate, olives, fish... you name it, and there's probably a sagra to celebrate. As in the photo above, many events employ long family style tables for friends and strangers to dine together in the streets.  The crowds at the Siena Palio The crowds at the Siena Palio Then there are thousands of events like the Palio in Siena, that insane bareback horse race where 17 neighborhoods compete. Over 40,000 people jam pack into the Campo to experience this race. Then each contrada (neighborhood) have communal dinners for thousands on the streets. Take this one event and multiply by literally thousands... all over Italy, Sicily and Sardinia. People communing together, shoulder to shoulder. Living, loving, eating, drinking, dancing, soaking in la Vita Bella. Imagine how crowded the Venice and Viareggion carnevale are each year. Now picture the seasonal markets. And the New Year's Eve crowds and rock concerts. Over 60 million Italians crushing, standing, chanting, singing, eating, marching... tutti insieme (all together). Italy Has a Vulnerable Elder Population In fact, Italy has nearly 20,000 people over 100 years old and has held the worlds record for the oldest living human nearly every year for the last couple of decades. Italy also has the second highest life expectancy in the world, too--at 83 years young. The reasons for this aging population are varied. The Mediterranean diet, hills and steps keep people in general good health. People tend to retire earlier, giving a more relaxed, stress free lifestyle to the elderly. The midday riposa offers a way the oldest family members can still share in a meal and visits with younger family members, which we all know provides a healthy family environment. They often live with their children and play and hug their grandchildren, who we now realize might carry the COVID-19 virus without symptoms and pass it on to the older family members. Without the stress of how older people are going to have health care (there is national healthcare in Italy), Italians feel comfort in knowing that if something bad happens to their health, they will be taken care of, for little or no cost. The one factor that might actually make the aging population more vulnerable to COVID-19 is the fact that many still smoke. There are far too many smokers in Italy in all age groups. COVID-19 does well in patients with compromised lungs. But of course, people living to healthy old age is not the reason why many might succumb if they contract the disease. This virus is different and powerfully and quickly attacks the vulnerable. We should applaud the Italians living to ripe old ages, if only that they made it in a vivacious, healthy way. They often live with their children and play and hug their grandchildren, who we now realize might carry the COVID-19 virus without even knowing. Ferragosto, the National Vacation Then there's vacation time. Italians don't stagger their summer vacations over three months like Americans. Most of Italy shuts down for Ferragosto in August, the month-long holiday season when Italians head for their campers or beach bungalows and crowd the beaches along its 4,723 miles of coastline. They literally pack the beaches and campsites or head up into the cooler mountains. During summer, there are thousands and thousands of major and minor concerts from the Veneto to Tuscany to Campania and Puglia. Indoor concerts, outdoor concerts, music festivals in rock, folk, opera, jazz... you name the music, there's a festival to suit any Italian's musical tastes. Can the Spread of COVID-19 be Really Blamed on the Culture?

I would argue, no. How can anyone blame a culture for doing what comes naturally? Italians are gregarious. They have close knit families. They love to hold festivals for just about anything God has graced their land with. They hug and kiss and walk arm-in-arm. COVID-19 has taken all of this away from them--at least for now. But you can see the evidence of of Italians sharing even this in a joyful way by banging pots and pans on their balconies... and by making music with all sorts of instruments, again, from their windows or balconies. They sing Bella Ciao together as the WWI partisans did several generations before. They sing their national anthem. They light candles. Even though they are apart, they are together in wearing masks and gloves and battling this unseen enemy, as they have done in the past for thousands of years. They are partisans. The closeness of Italians is not to blame. The emotional closeness and comraderie of the Italian people are the cure for what is ailing them. Andrà Tutto Bene --Jerry Finzi Our dear Mona Lisa apparently gets it. She picked up only as much toilet paper as she needs for a week. She has no kids and lives alone. her cat uses a kitty litter box. She's good to go. Think, "Need" vs "Want" vs "Hoarding". Hoarding supplies during this time will hurt us all. We've all seen the videos in Italy and in the U.S.... people fighting over rolls of toilet paper as they do a mad rush to get supplies during this coronavirus crisis. In Italy, the rest of Europe and here in the States, people are not being prevented from visiting their supermarkets and alimentari for food and other essentials. Here in Pennsylvania, Lisa's company has ordered all workers to work from home, Lucas is home because all the schools are closed, all "non essential" businesses are closing, BUT, all supermarkets and grocery stores are open and are being restocked after the first mad rush of last weekend. Most of our supermarkets now offer home delivery via online app, which helps reduce close contact. When I shopped last week, I wore latex gloves on both hands, wiped down the shopping cart's handle, and was careful not to stand too close to others. I also shopped at 7am when not many were in the supermarket. And although I didn't need toilet paper (we had stocked up two weeks earlier at a big box store with our normal 2 month supply), I was shocked to see the paper goods aisle empty. Calm down, tutti! Yes, this crisis is real--a fact of science and nature. But as long as we keep our heads and think not only of ourselves, but also our neighbors, we will all get through this. As the Italians say, andrà tutto bene -- everything will be fine. it may take some time, and there will be sacrifices, but we will come out of this in the end. --Jerry Finzi, GVI Some tips:

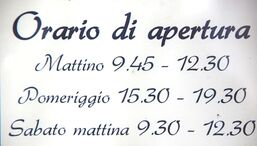

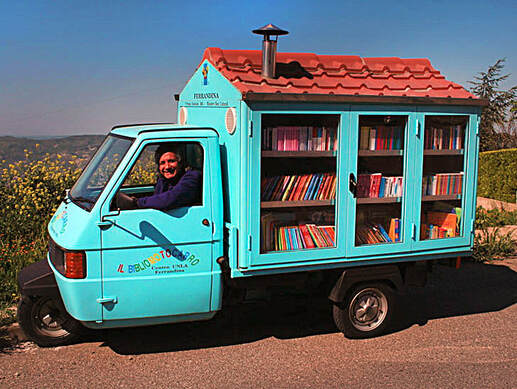

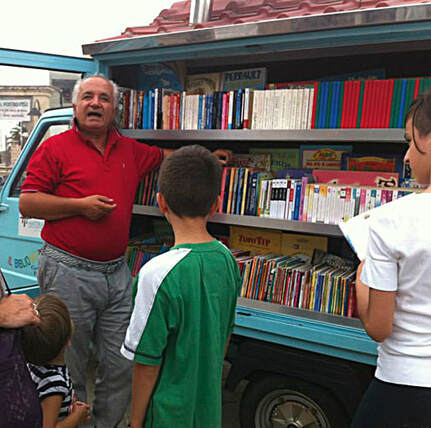

"Orario" means "hours" "Orario" means "hours" Most Italians work long hours. In the average business, their weekday hours are 9.00 am (9:00) to 1.00 pm (13:00) and from 2.30 pm (14:30) to 6.00 pm (18:00), from Monday to Friday. They use the 24 hour military clock. Many people will work well after 6.00 pm, especially true for managers and entrepreneurs. This is one of the reasons they take long lunches--called riposa--typically from 1 pm until 3 - 3:30 pm. Even most churches are closed from noon until 3 pm. There are many jobs which have their workers come in from Monday through Saturday, but they only work from 8.00 am to 2.00 pm. When a business is closed on Saturday, they might also add a few afternoon hours for their employees. According to Italian labor laws, the number of hours worked in a week can reach a maximum of 40. The average time, including overtime, cannot exceed 48 hours. Workers in Italy are guaranteed a minimum of 4 weeks paid days off for vacation and holidays. Some unions negotiate even longer periods of paid vacation/holiday days off. Lunch breaks are typically shorter in large cities and restaurants are open during the lunch hours. In smaller towns, even restaurants will be closed during riposa because most people prefer to eat at home. (But food is available at "bars", which are open). In almost all cases, many shops, even in large cities, will be closed for riposa with their hours listed on the door. In addition, during the August holiday season of Ferragosto, when workers take from 2-4 weeks off for holiday, you might see a sign on shop or restaurant doors saying "Chiuso Per Ferie" (Closed for Vacation) with a date when they will return from vacation. Italy is know for passionate people, and Antonio La Cava from Matera is one of them. He's passionate about sharing the glory of books with children. La Cava carries a telling surname, as Matera is the city of caves, or Sassi, when people have been living in cave homes for tens of thousands of years. Retired as a schoolteacher after 42 years but couldn't stop spreading knowledge to il bambini of his region of Bacilicata. So in 2003 he bought a used tre-ruote (three wheeler) Ape mini truck and created his Bibliomotocarro, a portable library that houses 700 books. La Cava travels over 500 kilometers each week to 8 regular stops on his route. The children know of his arrival by the sound of organ music coming from his unique vehicle. The children run to greet him as if some TV star is showing up. He also funds his efforts, pays for fuel, repairs and buys the books from his own pocket. His passion for the love of the written word will be carried on--certainly by the many children on his route. --Jerry Finzi “A disinterest in reading often starts in schools where the technique is taught, but it’s not being accompanied by love. Reading should be a pleasure, not a duty.” --Antonio La Cava  by David Dalessandro from Sharon, Pennsylvania Need some guidance here, so I thought coming to my paisans at Italian Gardeners on Facebook would be a good place to go... While pulling my tomato plants today it hit me that I was alone. My knowledge of gardening, weak as it is, came most from my Father who got his knowledge from his Father who was an immigrant to the U.S. from Foggia. My grandfather worked for Carnegie Steel in Farrell, PA as a janitor for the office. Carnegie had provided a home for him at a cost of $2.200. Company homes without a bathroom were $2,000 so Pasquale went for the better model. Companies did that in those days...this was 1925. The company then deducted so much from his pay and he had a decent house where he could walk to work. Another thing the company did for employees was to provide garden space. Carnegie owned extra land in Wheatland, PA and the company would plow the land--at no cost to workers--and let employees claim part of it to put in their own garden. My grandfather took great advantage of that and every year would plant tomatoes, potatoes, beans and other vegetables that would help to feed his family. It was in this garden that he taught my Father, who then taught me. So, fast forward to today, about 80 years later. I am stuck on the Teaching Thing. My children are grown and not really interested. My daughter is in El Paso, Texas and my son, still living with us, is working to become a tennis professional. Neither are much interested in gardening.  100 year-old Portland gardener, Ulisse Edera. Photo by Keith Skelton. 100 year-old Portland gardener, Ulisse Edera. Photo by Keith Skelton. But I love it. I enjoy starting the seeds, tilling the ground, fertilizing and watching the plants grow. Because of the abundance God has provided, I also can many jars of tomato, sauce and hot peppers. Again, not because I have to, like my Grandfather had to, but because I want to. But, I am afraid that I am the last of the line. My uncles are gone. My Father is gone. My wife humors me and lets me do my thing in the garden. It bothers me that it is likely to end here. And, I fear I am not alone. No one at work talks about a garden. No one else in the neighborhood has one. Just me. It is a shame, I think, that the accumulated knowledge of at least three generations will end. Do any of you have the same concerns? Do you have children or grandchildren who work with you and ask questions and help pull weeds and can tomatoes and wonder why something is growing or not? Let me know...and if you have answers for this situation, I would love to hear them. Thank you so much, my paisans.  Passing on the tradition Passing on the tradition And my Thoughts... And I totally agree with David, which is why I've asked his permission to post his words here on Grand Voyage Italy. After all, we are #AllAboutItaly here... and we're all about the Truths about our culture. I feel David is correct--too many young people today are detached from their cultural roots and have no idea where their food comes from, especially true with Italian-Americans. When one takes a Voyage around Italy, all you see is gardens--everywhere, in tiny front yards, hanging on walls, on balconies and terraces and in pot gardens surrounding people's front doors. It doesn't matter if they have lemons and pomegranates on their patio or just a pot of basil on their windowsill--it seems that everyone grows something edible. We should all strive to teach our children the value of home grown, healthy food, like I've done for my own son, Lucas. Here's a photo of him with his tomato harvest at 4 years old... He's 15 now and looks forward to each February when we go down into the cellar, sort out our seeds and start our heirloom seeds that we save each year from our garden. He now looks forward to the tomatoes we grow as if they are old friends... Eva Purple Ball, Olivette Juane, Giant Belgium, Jersey Devil and more. He also is learning to cook using the vegetables harvested from our garden, and even when we don't grow them ourselves, he now knows how to smack a cantaloupe, listening for the lowest pitched sound (a sign of ripeness), or check a peach's ripeness with his nose, as my Dad taught me. Gardening is part of the Italian soul. Pass it on, people. Pass it on... --Jerry Finzi And for more on the subject of gardening... Creating a Hanging Italian Wall Garden

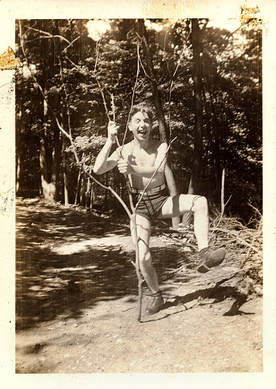

Bicycles - Italian Garden Style My New Favorite Tomato: Striped Roma San Marzano Tomatoes: Accept No Imitations! How the Tomato Became Part of Italian Culture Only in Italy: Strange Veggies from La Belle Paese To see how you can create an Italian Garden of your own, check out the Grand Voyage Italy Shop on Amazon.  And then there were three. My brother Kenneth and the twins with Mom and Dad. And then there were three. My brother Kenneth and the twins with Mom and Dad. I suppose the first gift to my father, Sal, was his first two children... the "Twins", Joan and Barbara, born three days apart but healthy, nonetheless. This was the start of my immigrant Dad's entry into fatherhood. Just when other men were being drafted into the U.S. army to fight in World War II, he suddenly was burdened not with one, but two children--this was in 1942 when twins were a mere 1% of all births. His nickname, Sally-Boy was coming to an end. Things had just gotten serious. When he saw only one baby on that first day, the doctor casually told him, "The second one just isn't ready yet". He couldn't rest assured that everything was OK until the second was born three days later, an event that placed my mother's photo holding the two of them on the pages of New York City's Daily News. The war started and my Dad worked in a defense plant making springs for tanks. As you can see from the photo above, my father was not only a proud father, but a rather goofy one. Always the joker... that was his first real gift to his children. John and Barbara were to be followed by Kenneth, Joyce-Ann and myself, the "baby" of the brood. Somehow, Dad provided. Before he was married, he and his brother had a "Three Legged Horse and Cart" and sold fruit and vegetables to the seamen down at Hoboken harbor. He had dreams of having his own Italian delicatessen or market someday, but he opted to have security for his family, always working for others for a steady salary. He clothed and fed us by being a grocery and deli man his entire life. This was another gift to us all.  Always the clown, even as a young man Always the clown, even as a young man Dad always played the fool, constantly at the ready to play a joke on us, to get us to laugh, putting us close to sheer embarrassment. At the beach he always insisted that we bury him under the sand, head exposed with his shoes stuck out 12' away from his head under a ridiculously long body of sand. Everyone passing by loved it. After a while (and his nap) we'd mockingly wind up stomping on his sandy "stomach" (safely clear of his real one) to the amusement of others around us, aside from my mother, who always made like she didn't know him. When we were the only Italian family going to a New Jersey mountain lake previously only frequented by Germans, my father offered them meatballs, sausage and spaghetti and became the biggest clown in the middle of the lake, making his infamous sea monster growl that echoed from the mountainside. He taught us to put small, rounded stream stones into the barbecue so they would explode and scare the heck out of Mom when she was grilling burgers and hot dogs. He came up with the idea to put the watermelon in the stream to keep it cool all afternoon--which worked great except for one day when my sister and I had to run, splashing down the stream to recapture it after it got loose. These were also gifts from Dad. Dad always took me fishing and crabbing down the abandoned docks and piers along the Hudson River. He taught me how to get past chain link fences and avoid guard houses to find the best fishing spot. I remember long, hot afternoons, the smell of fish and tar, and the pinching of the crabs we'd catch in our box crab nets. Some days we'd be there so long until the tide shifted on the Hudson... in the morning the river would be flowing out to sea, and in the afternoon it the river would actually flow upstream. He'd also drop some bait lines from the wooden pilings using little screw-in springs with bells on them. A big "Mama eel" would latch on to a hook, the bell would ring and Dad would have dinner for him and Mom. One day we caught a big eel in the crab net and a big Jersey blue crab on the drop line. At the end of a long day, we'd head home with a bucket full of beautiful blue crabs and perhaps a few eels to fry up. Again, more gifts from Dad. Of course, we all bought Dad gifts for Father's Day. I remember saving the deposit money I earned from collecting empty soda bottles and buying him a bottle of shaving lotion or a pair of socks. A I got older, my gifts were many and varied: bottles of Amaretto, a fishing rod, a lop-eared rabbit, a 3 foot tall basket woven bottle of Chianti, a turquoise pocket knife, a trip to Caesar's Palace in Atlantic City, and odd assortments of power and garden tools.

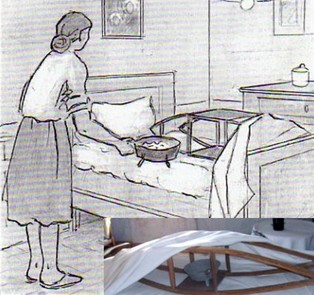

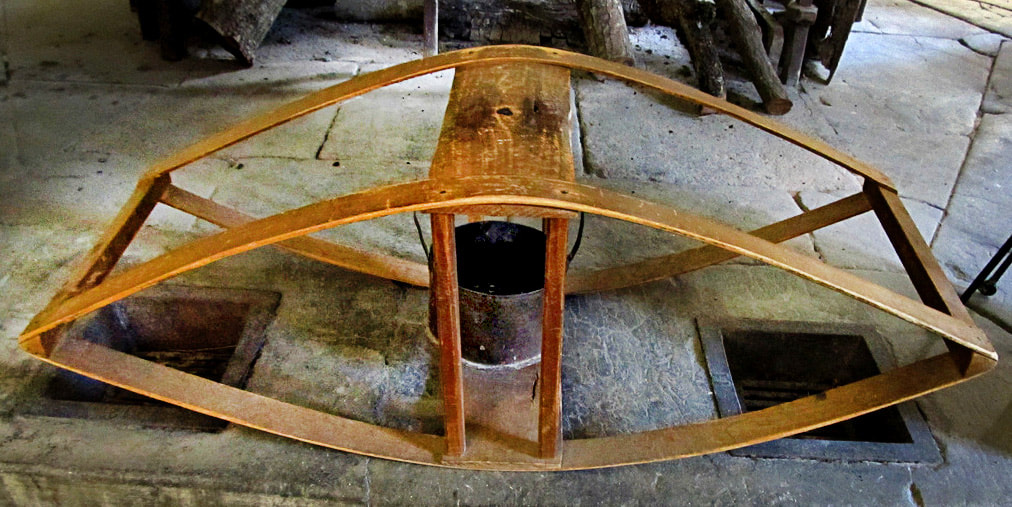

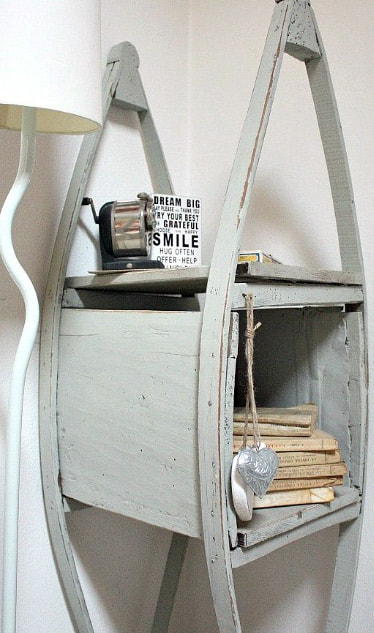

But looking back, my gifts never matched the gifts he gave to me. He gave rock-solid, undeniable love and pride toward me. He gave simple, sound advice when I most needed it. He even gave me the gift of my wife and son when one day challenging me, "So, when are you going to marry that girl? You spend all your time with her anyway!" Thanks Dad... for everything. --Jerry Finzi  OK. Now, don't scream, "sacrilege". Let me explain... More than 100 years ago in Italy, people really would place the Nun and Priest into their beds to warm things up. The Suora e Prete (Nun and Priest) was the name of a device used to warm the bed and blankets just before bedtime. In northern dialect, they might be called Frà dël let, or Bed Brother. They were often used until the early 1900's, and perhaps even later on in poorer parts of Italy. The Nun, or scaldaletto (warming bowl), was a removable round bowl with handle, into which hot coals (with ashes to slow down their cooling) were placed. Placing hot bricks in place of the Nun was also an option. Wealthier folks could afford rocchetti--small cylindrical containers filled with compressed coal dust. They were heated in the fireplace and lasted a lot longer than loose coals and ash. The Priest constituted a frame that housed the Nun along with its hot embers, holding sheets and blankets well above the coals to prevent them from scorching or bursting into flames entirely. Sometimes the Nun had a lid with decorative perforations which allowed the heat to escape. The Nun and Priest also helped dry the damp sheets--a common problem in the cold and damp of stone houses during the winter months. What are the roots of the name? Many consider the draping bed coverings to look like the draping of a nun's hood. Why "Priest" then? With Italians' tendency to be shockingly irreverent, we can only guess. Perhaps there is a reason the priest is on top... of course, I mean to hold in the heat of the Nun under "him". Wait... I'm getting myself into trouble here.... The interesting thing is, the Nun and Priest is still being made today, albeit in electric versions. When considering the thick stone walls and dampness of old Italian houses, this contraption might seem like a very good idea to warm up the bed on a cold windy night. Very common in Italian antique stores and flea markets, many people have taken to finding new uses for the Nun and Priest, especially as decorating objects. The Monk, a Close Cousin... Another tool to heat the bed was il Monaco or also Mariteddu (the Monk), a kind of terracotta amphora that was filled with boiling water and placed under the covers. The rather thick, heavy ceramic would retain heat for long periods of time and release it slowly, creating a gentle warmth under the covers. Unlike the Nun and Priest which warmed the bed before you got in, the Monk could be kept in bed during the night with you. Oh no... here I go again. I'll stop now. --Jerry Finzi This might also interest you...

Italian Warmth from the Poor Mans' Hearth: Il Braciere, the Brazier While researching another subject using Google Earth, I came across this unusual scene just outside of Canosa di Puglia... a beautifully built Highway to Nowhere.

Oddly, the "street view" from several years ago shows nothing but dirt roads and farm fields. The satellite view taken in 2017 shows this beautifully built highway and a wonderfully wide roundabout in the middle. The only problem is, it goes nowhere and comes from no where. There are dirt roads and vineyards around all sides and the paved intersections intersect with dirt roads. There are no structures within the "development" area... just olives and grape vines. Go figure. Perhaps the regional government thought, "If we build it, they will come." --Jerry Finzi There is that old saying (or aphorism), “Don’t raise the bridge, lower the river" that every engineering student knows. It describes the attitude about the obvious: there are no obstacles in getting things done. Just analyze the problem, and think of a way around it. But this doesn't usually mean literally. "Lowering the river" is what lies behind the design of most canal locks in the world. I've even seen canals built on viaducts, making the water travel over an obstacle, like railroad tracks or a road. But I've never quite seen the Italian solution to the problem illustrated above. In Manhattan, for example, if a work crew arrived, permits in hand, ready to dig a ditch for a sewer or communication cables, a call to the City's tow trucks solve the problem in no time at all. Tow the car out of the work zone. Done. In Italy, however, perhaps because of the lack of a reliable city department that would actually handle this problem--before the 12-3pm riposa--these workers figured they wouldn't wait for anyone else and solved the problem their way. Furbo. Look out for your own interests. Get the job done and get back to your own life. Why worry about some future contractor trying to locate that underground run of cable that he thinks should be in a straight line.

Besides, "Why have someone's car towed away and cause someone else problems? It might be my friend's cousin, or my cousin's cousin, or, Dio mio... someone's nonna!" --Jerry Finzi |

On AMAZON:

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed