by Jerry Finzi While exploring the villages of the Amalfi Coast, Voyagers are certain to notice that the lemons there are larger than they are used to. They are sure to come across the Sfusato lemon (about two to three times the size of a supermarket lemon) and will be further shocked when they are confronted with the giant-sized, Cedro Citron variety of lemons. They are beastly looking things, with a pebbly surface, strange shapes with a large nipple at one end, and are often as big as your head!  Cedri are primarily found in Italy, from the Italian Riviera down to the Amalfi Coast, though they are occasionally spotted in France, Isreal and even exported to Britain. There are three different citron types: acidic, non-acidic and pulpless. Of the different cultivars, the acidic Diamante is more common in Italy. Cedro citrons are usually up to three to four times the length of common lemons and can measure between 10 and 15 inches in diameter. They can weight up to 3-4 pounds each. The pebbly surface ripens from green to a bright yellow--both colors can be harvested, the peak season being fall and winter. Most--about 70%--of the lemon is white pith from 2-5 inches thick with a soft texture and almost sweet lemony fragrance. In its center is a small amount of segmented pulp with a few pale seeds. This lemon is fairly dry and not used for its juice and the taste is milder than a common lemon.  The pith can be eaten raw or cooked: in salads, atop bruschetta, in jams and preserves, in risotto or pickled. The rind of this citron is very aromatic and a bit sweet, and is used to produce "citron", or candied lemon (used in Italian celebration breads and cakes, like panettone). Some claim it can be a remedy for hangovers, coughs and indigestion. Since the Renaissance, the oils from the skin have also been used in perfumery and cosmetics due to their delicate and fragrant scent. If cooking while in Italy (or if you can get some cedri at home), try these recipes: Risotto alla Sorrento with Fennel and Sage 1 Cedro lemon 1-1/2 cups rice for risotto (Carnaroli, Vialone Nano or Arborio) 1-1/4 cups freshly grated parmesan 1 tablespoon unsalted butter, plus another tablespoon to finish 4 tablespoons Extra virgin olive oil 1 head of finoccio (bulbing fennel) - finely diced 3 stalks celery - finely diced 1 cup white white Vermouth 1 quart chicken stock 4 large julienned sage leaves (or 1/2 teaspoon dried-crushed) Sea salt and freshly ground black pepper to taste Directions

Candied Chocolate Cedro Strips Recipe (A great holiday snack) 1 - 2 pound cedro 1 cup sugar 1 pint water 3-5 ounces bitter sweet chocolate

You can store these in an airtight container and serve at the end of a meal with fruit, nuts, biscotti and espresso. © GVI 2018 You might also be interest in:

When Life Gives Them Lemons, Italians Make Limoncello Amalfi Lemon and Chicken Pasta Lemon and Turkey Pasta with Prosecco  One of many ovens at Pompeii One of many ovens at Pompeii Excerpt from an article by Kristan Melia on Culinary Backstreets/Naples There is evidence that wood-fired ovens similar to the ones used in Naples today were employed by the Ancient Greeks, and some assume that Greek mariners brought this technology with them to the city. Thanks to Vesuvius’ explosive eruption in 79 AD, we can turn to Pompeii for gustatory evidence. Archeologists have unearthed 33 domed clay ovens, complete with chimneys, on the grounds of Pompeii. We know that bread was an important part of the Pompeian diet. The very volcano that would eventually lead to Pompeii’s demise actually contributed to her rise as an early producer of baked goods. The Greek geographer, philosopher and historian Strabo observed that the area around Pompeii and Naples as a result of the soil’s volcanic fecundity, was “the most blessed of all plains, and round about it lie fruitful hills.” It turns out the slopes of Vesuvius were ideal for the growth of cereal grains, and that bread was to become a symbol of Pompeii. An engraving on the entrance to the walled town reads matter-of-factly, “Traveler, you enjoy bread at Pompeii.” The process of grinding the grain to make the bread was arduous. However, the volcanic black lava rock of the region was ideal for shaping tools to grind the local cereals. The practice of crushing, grinding and pounding wheat through a mill was known as pistor and by 160 BC, as Cato documents, the tradesmen responsible for this grinding were known as pistore. When coupled with the ingenious design of the beehive clay oven with chimney, this gave rise to the baking of deceivingly simple, pliable, leavened breads called pinse, so named for the grinding and pounding required to produce them. The pinse would travel through the Roman Empire; years later, we would know its cousins as pissaladiere in Provence, pita in the Middle East and pizza in Naples.  Vesta Vesta In the early days of bread baking in Pompeii, pistore worshiped the god Fornax, the ancient personification of the oven. It is from Fornax that we also derive the word forno (oven), as in forno a legna (wood oven). Every year on February 17, Pompeii’s guild of oven tenders celebrated Fornacalia, lighting and feeding fires in much the same way modern Neapolitans light fires in commemoration of Saint Anthony the Abbot’s day. Years later, Pompeii’s bakers would switch their pious devotions to the goddess Vesta, protector of the hearth – perhaps a testament to the reverence they harbored for the fire that fueled their precious ovens. For all the early success Vesuvius afforded Pompeii’s vibrant grain economy, the volcano would eventually become the town’s undoing. But the traditions of the pistore live on today in the ancient vicolos and back alleys that thread through Naples’ historic center. CLICK HERE TO READ MORE...

Chie hat pane mai non morit.--Sardinia Proverb

One who has bread never dies.

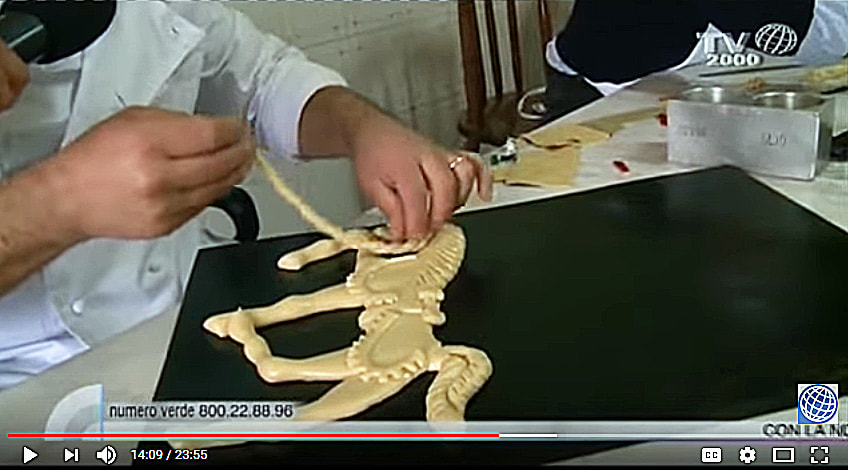

In Sardinian bakeries there is a time honored tradition of elaborate and intricate decoration of celebration breads for weddings and also for Pasqua (Easter), called

Pane Pasquelina, or in local dialect known as Su Coccoi or Pane Coccoi. The designs recall ancient symbols from the many cultural influences in Sardinia. The shapes include the crown, wreathes, the chick, a girl, doves, fish, small baskets, fruits and flowers. Especially for Easter, whole eggs are incorporated into each design, sometimes hidden but often exposed within the design theme. These breads are considered symbols of fertility and good luck. When you look at the intricacies of these artisinal breads, it's surprising to think the only tools used are a small knife and scissors.

Two interesting shapes are called Sa Pippia and Lazzaro. Sa Pippia is a doll-shaped bread with seven legs, one for each day of the Holy Week. This bread was used as an Easter Advent Calendar, one leg given to a child each day leading up to Easter Sunday. Lazzaro represents the body of Lazarus wrapped in a shroud, a symbol of resurrection.

Watch as the Nonni teach the younger women how to create Pane Coccoi

and then bake them in a community oven.

If you'd like to try making these special breads, here is an authentic Sardinian recipe that I translated and converted...

Recipe

Shaping the Dough

Baking Preheat your oven to 450 F degrees with the pizza stone on the middle rack. Place a sheet pan on the bottom or lowest rack of your oven at this point. I suggest using a pizza peel to transfer your breads into the oven and directly onto the pizza stone. If you don't have one, you can use an up-turned sheet pan lined with parchment paper (the paper will slide onto the stone with the dough). Alternately, sprinkle the back of the sheet pan with course cornmeal, then place your shaped breads on top. The cornmeal acts like ball bearings to slide your breads onto the stone. I don't recommend baking your breads on pans simply because the pans would be cold when placed into the oven. If you do want to use pans instead of a pizza stone, use sturdy, heavy dark pans. They will heat up faster. Just before placing your breads into your oven, pour about 1/4 cup of water into the hot sheet pan on the lower rack to create steam. Immediately shut the oven door. Quickly transferring your formed breads into the oven, bake for the first 10 minutes at 450 degrees, then lower the temperature to 350 F degrees and continue cooking for another 20-25 minutes. You might want to quickly spray some water onto the oven's side walls halfway through the baking. Check the browning of the bread and adjust according to your oven. These breads should be a very light tan with a fine textured crumb interior. Remove from the oven and place on cooling racks to dry and cool completely. There is another version that adds eggs, so you can experiment in adding eggs while you compensate by adding more flour. You can still eyeball the smoothness and elasticity of the dough when mixing. Remember, making dough for breads and pizza is a feel thing, varying depending on the humidity of the day. Have a great celebration! Buona Pasqua! --Jerry Finzi

You might also be interested in...

Our Pane di Pasqua Recipe Vintage Italian Easter Cards Decorated Italian Easter Eggs How Italians Celebrate Easter Celebrating Easter in Italy

SHARE ON YOUR SOCIAL MEDIA SITE

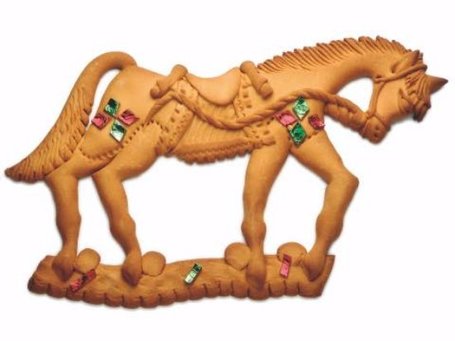

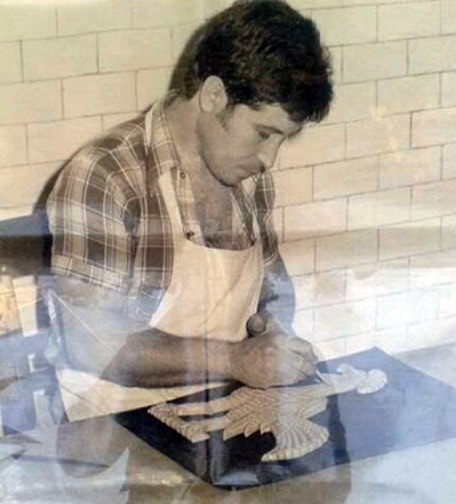

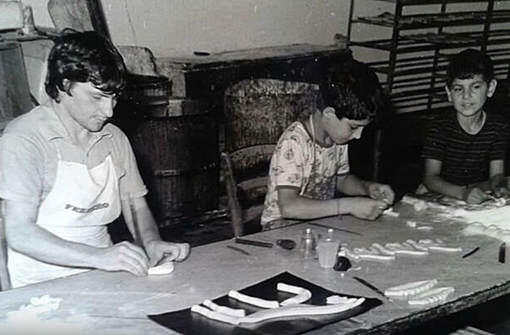

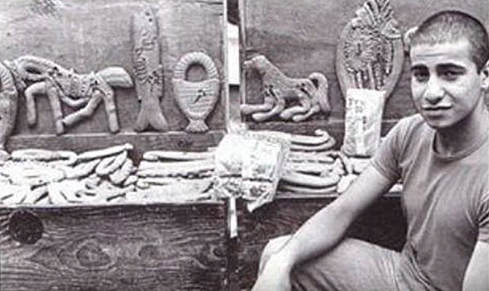

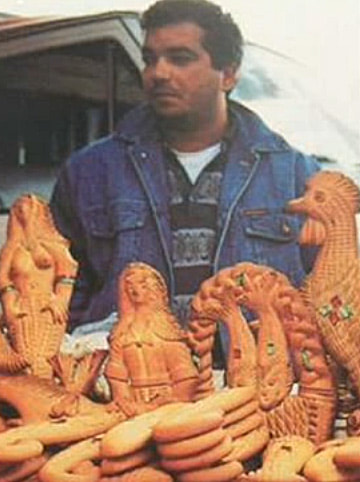

The ancient town of of Soriano Calabro sits between the hills of Calabria and is known for the hard, spiced and shaped biscuits known as Mostaccioli (also, Mastazzola, Mustazzoli). They are traditionally made using grape must, a byproduct from wine-making process. These ornately decorated and shaped treats are popular for festivals, weddings, Christmas and Easter. The more traditional shapes include a parma (the palm), u panaru (the basket), a grasta (the heart), u pisci spada (the swordfish), and a sirena (the siren). Aside from the myriad of shapes, they are decorated with colored foil and some might even have been created using different colors of dough. These are not molded but cut and assembled by hand.  You can still see Mastazzolari (vendors) selling plastic wrapped Mostaccioli from their wooden trunks at sagre in the region, with parents buying ones shaped like a horse or bird for their children, or the devoted purchasing one shaped like a saint, angel, fish or basket as an offering on a saint's day. A heart shaped one might be given on a wedding, engagement or on San Valentino's day.  Or, if you prefer, you can watch the video right here... Click below. Creating Mostaccioli Mastazzolari and How They Sell Their Wares

My dad, Sal was a great cook. He loved food and worked with it every day, starting out selling produce down by the Hoboken waterfront with his brother Anselmo and their "three-legged (lame) horse " and cart. Later on he worked as a greengrocer and as a deli man. He even grew food in our tiny backyard garden--especially tomatoes. When his customers saw him around the county, they'd shout out "There's My Baloney Man!" My Mom did all the daily cooking--soups, chicken, pastas and all that, but my Dad did the special meals: Thanksgiving turkey, Christmas Baked Ham, Roast Beef and lots of other Italian specialties like smelts, fried eel, and quick lunches like his "potatoes and egg" frittata. He was always great at making something from pretty much anything he found in the fridge. But what I loved best was the way he made fist-sized meatballs in the deli. Only one of them would fit into a pint sized container. It was always a special treat when he brought some home. One of these giants on a plate with spaghetti was a feast--one meatball equal to about 4 or 5 the way my mother made them. No need to ask for any other meatballs--one was certainly more than enough. Once every few years, in honor of Dad, I set out to make his meatballs, his way. His size. In this recipe, we used about 4 pounds of beef--ground chuck. You can use your own family's meatballs recipe or ours HERE. The ingredients would need to be increased to account for the 4 pounds (if you're making a lot), or simply make less meatballs. Four pounds would give you from 6-8 giant meatballs--2 pounds, probably 4 meatballs.

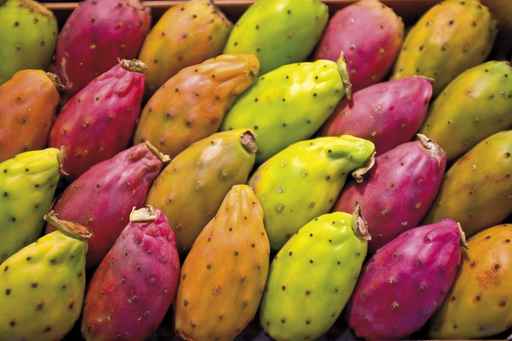

In the bottom of a roasting pan, I placed light olive oil, about 1/4" deep. The meatballs are placed in the pan and brushed with Extra Virgin Olive Oil to help the browning. The oven should be pre-heated to 450 F at first, then roasting the meatballs, uncovered for about 30 minutes. Next, cover lightly with foil and turn the oven down to 350 F and bake for another 30-45 minutes (ovens vary). Check occasionally to ensure the bottoms aren't burning. Turn the meatballs over a few times if necessary. You want them nicely browned, or until the internal temperature reaches 165 F (using an instant digital probe thermometer). After the meatballs are done, you can serve over pasta with some of your tomato sauce, or place them into a large pot of your Sugo (Sunday Gravy) to flavor the sauce. You can also cut up one meatball to make a large meatball hero (sub) sandwich, topped with grated parmagiano and toasted in the oven, or smash one with sauce and sliced provolone cheese inside a large flatbread, like the type used to make a muffaletta sandwich. You might also serve half a meatball, cut side down on separate plates with pasta for an intimate supper... calling the half-moon dish Mezzaluna. "When the Moon Hits Your Eye... That's Amore!" No matter how you enjoy them, you'll love making these huge polpette--my dad, Sal's Giant Meatballs. Buon appetito! --Jerry Finzi (Share this post with your friends!)  The fruits of the Prickly Pear in Italy are known as Fichi d'India (India Pears), marketed in America with the friendlier, less dangerous name of Cactus Pears. The plant was first introduced into Europe after the discovery of the Americas by Columbus. The fruits were named fichio d’India (Indian fig) because when Christopher Columbus arrived in the new continent and saw prickly pears he thought he was in India. These colorful fruits make a sweet snack or a margarita mixer. Unlike Mexico and other countries, Italy doesn't use the cactus paddles, but simply loves this pear shaped fruit. Intensive plantations across Sicily and the southern mainland make it only second to Mexico in cactus fruit production.  Large, crunchy seeds Large, crunchy seeds In reality, the word “prickly” lessons the dangerous aspect of the spines of this fruit. But it's not the obvious large spines of this cactus that are the problem, the real danger is from the tiny, nearly invisible hair-like spines that completely cover the skin of the fruit that you have to watch out for. If you touch them with your bare hands, you won't be able to wash them off... microscopic hooks dig into your skin causing burning pain. What do they taste like? Many say that Fichi d'India are sweet but not too sweet. Some describe the flavor like a fig crossed with a plum. They are also very seedy, with big, hard seeds. Some like to feel the crunch of the seeds between their teeth, while others eat them as they do pomegranates, swallowing seeds along with the gelatinous flesh (think, "fiber"). In southern Italy (especially Sicily) people love eating them fresh. You will often find them pre-skinned and ready to eat in market displays. The taste varies with the color--white, orange and red. Some say that the red ones have more flavor than the other colors. One interesting tradition is winery owners giving the fruit to their grape-pickers for breakfast to prevent them from eating grapes during the harvesting. This tradition is still kept today. You'll find the best ones during its harvest time in Sicily, from October to December. There is also a Sagra del FicoIndia in the town of Roccapalumba in Palermo Province held usually in the second week of October. During the feast, the town’s streets will be alive with workshops about how to peel and eat the tuna (Sicilian word for the fruit) of the cactus, how to prepare it for consumption, and there will be opportunities to taste products and dishes made from the plant–everything from honey to liquor to a recipe called scuzzulata. More than 30,000 people attend.  Culinary Use Besides being eaten fresh, Fichi d'India can be used in salads, vinaigrette and made into granita, jams or honey. They are also used in Sicilian cakes, such as Buccellato, which is very common at Christmas time. You can drink juice from the fichi d'India, but it really needs some lemon added for additional acid. In fact, it is often used in commercial drinks as a flavoring.  Many make a home brew--Liquore al fico d’india--from the fruit in a similar manner as one would make limoncello, placing the cut up fruit in jars of alcohol with a sugar-syrup and fermenting in a dark place. The resulting liquor is best served very cold. The fruit is high in vitamin C, antioxidants. calcium and phosphorus. --Jerry Finzi This video shows how to skin and harvest a Fichi d'India fresh from the cactus plant--without getting hurt. Here are two Nonnas showing the sensible method of skinning the Fichi d'India by soaking them first in a bucket of water.

The Ligurian region of Italy lies along the border of France and is home to a very special fresh pasta called Corzetti. In this article, we will only discuss corzetti stampae, coin-like fresh pasta cut and embossed with various decorative patterns, one-by-one, using a special wooden stamping tool, itself specially hand-made by artisan wood craftsmen using both wood-turning chip carving techniques. They are typically made out of maple, or fruit woods like pear or apple. In the Genovese dialect these coin pastas are called curzetti. Making corzetti is very laborious and time consuming, and as such are typically made only during the holidays or for special occasions.

Figure-Eight shaped Figure-Eight shaped

There are also a different type of Corzetti from the Val Polcevera, one of the principal valleys of the area of Genoa, that are made in "figure eight" shape and look nothing like coins.

Genovini d'0ro gold coins Genovini d'0ro gold coins

In Latin, the word for cross is crux. Cröxe in Genovese dialect also means cross. So one might realize that the word croxetti (in Italian), might be referring to the "little cross"--gold coins that were made in the 12th century called Genovini d'0ro. It's no surprise that many refer to Crozetti as "coins".

It is also possible that during the Renaissance they were used for weddings with the coats of arms of both bride and groom, one each on either side. Some claim that one local family made corzetti to impress Maria Luigia of Borbone, just before leaving for France to marry Napoleon.

There are some very simple and traditional recipes corzetti sauces. One of the oldest sauces is from medieval times, a pesto made with marjoram, pine nuts, walnuts, olive oil and parmesan cheese. Another similar recipes uses melted butter in place of olive oil, and places the ingredients in the hot pan rather than mashing into a pesto. Here is another fantastic sauce made using walnuts... Sugo di noci 1 ½ cups chopped walnuts 1 medium size clove garlic 1/2 cup of fresh ciabatta bread, cubed, soaked in a bit of milk, then squeezed nearly dry. 1/4 cup fresh marjoram leaves 3 -4 tablespoons grated Parmigiano Reggiano 1/4 cup Extra Virgin Olive Oil a pinch of salt Run all the ingredients in a blender until smooth, with some texture remaining. This sauce can be used as any pesto, tossing with the pasta. If you like, you can also place the sauce into a large saute pan and heat along with the corzetti.

Making Corzetti

The ingredients for the pasta are for 4 persons. 3 1/3 cups all purpose flour. 5 egg yolks 1/4 teaspoon salt 1 cup of white wine

I hope you take the time to make corzetti for your next special event or holiday meal. Let us know how it turned out!

Ciao... --Jerry Finzi |

Archives

July 2023

Categories

All

|