|

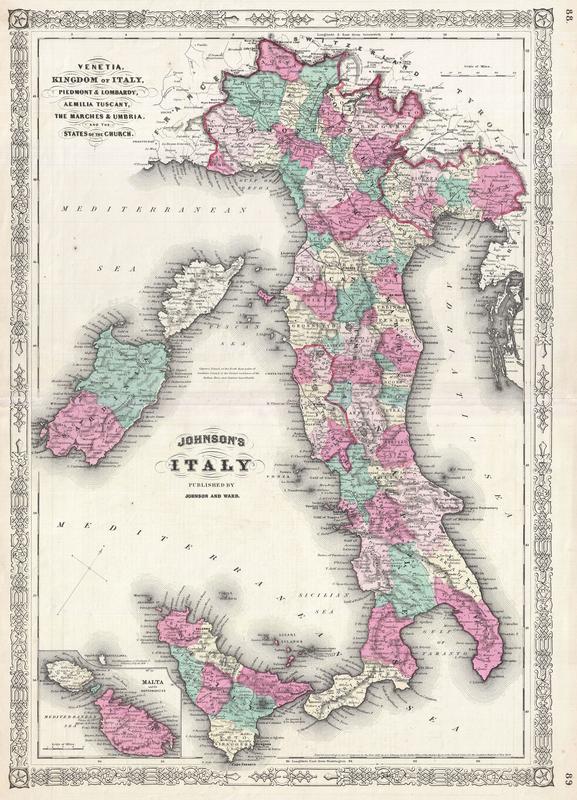

A beautiful example of A. J. Johnson’s 1866 map of Italy. Johnson first introduced this map in his 1863 atlas and it represents a substantial re-engraving of his original two part plate. Johnson's reconsideration of his Italy map was most likely related to Italy's unification in the 1860s. No longer a collection of independent states, Italy now needed to be represented as a cohesive whole. In order to accommodate this Johnson reorients his map to the northwest, allowing the boot to fill a single vertical page while leaving space to fully depict Sardinia and Corsica. In the lower right quadrant there is a inset map of Malta. Throughout, Johnson identifies various cities, towns, rivers and assortment of additional topographical details. Features the fretwork style border common to Johnson’s atlas work from 1864 to 1869. Published by A. J. Johnson and Ward as plate numbers 88 and 89 in the 1866 edition of Johnson’s New Illustrated Family Atlas .

His name doesn’t sound Irish when you read it in the Spanish naval documents, but Guillermo Herries (a Portuguese translation of his name) was really William Harris of Galway. It’s no surprise that Irish children never heard of “Guillermo” even though he was a member of Columbus’ First Voyage with the Nina, Pinta and Santa Maria…

As historians have theorized based on their evidence, William Harris first met Columbus at St Nicholas’ Church in Galway in 1477. Some say he discussed strange, unknown plant seeds and other objects washing up along the shoreline in Ireland possibly from some far off land, while others think Harris boasted to Columbus that he had actually sailed to those lands to the west. Columbus was also emboldened by stories he heard of the 6th century monk, St. Brendan and his voyage to the New World. It’s not too difficult to believe that Harris might have reached America before 1492, since it’s been proven that Leif Erickson had also been there hundreds of years earlier in a failed attempt at setting up a colony in the northern regions. “Guillermo Herries” is one of 38 people listed as being left by Columbus in Haiti to form the first European settlement in the New World. In the end, after a short time, the native population slaughtered them all. Still, we must honor both the Italians, Portuguese and even the Irishman that took part in opening up the New World to European culture… Happy Saint Patrick's Day a tutti! --Jerry Finzi By Gianni Pezzano

The decision to migrate is never easy but, no matter how hard the decision, at the moment of departure we never understand the true price paid by those who leave a country for a new life. It will then be the cruelty of time that will uncover the true pain caused by long distances and the ones who feel it are not only the migrants, but also the children and descendants. From telegrams to messages When I woke up Saturday morning there was a message on my mobile phone that I had feared since the first day in Italy. My uncle Rocco had passed away, the last of my father’s eight brothers and sisters and with him an entire generation of the paternal side of my family ended. It will not be the last such message and they never become because less painful, in fact… After the first moment of sadness, which has grown since then, I remembered my mother’s scream that evening fifty years ago when the telegram arrived to tell us of the death of Nonno (grandfather). The change of technology has done nothing to reduce the pain. That was my first true experience of the migrant’s pain. Two years before my maternal grandparents had come to Australia to meet the new in-laws and above all the grandchildren that they knew only from a few brief words in the rare telephone calls and the photos sent during the long exchange of letters between my mother and Nonna (grandmother). Sadly I never met my paternal grandparents. Nonno had died before my parents’ wedding and I was too young to remember when Nonna followed a few years later. Read the entire article HERE (in both Italian and English)... The shameful treatment of Italian Immigrants during WWII show America’s propensity for xenophobic hysteria Their movements were restricted, their homes raided; in some cases, they were interned The men in suits were at the Maiorana family’s Monterey, California, home again. Mike, the family’s young son, watched as the agents rummaged through their belongings in search of guns, cameras, and shortwave radios. And again, they found nothing. This was during World War II, and the FBI had declared Mike’s mother an “enemy alien.” The sole source of evidence for this allegation was that she was Italian.

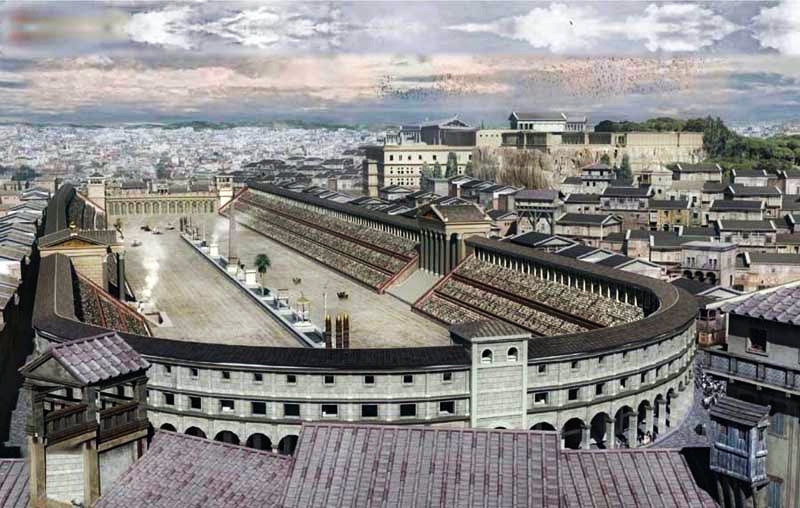

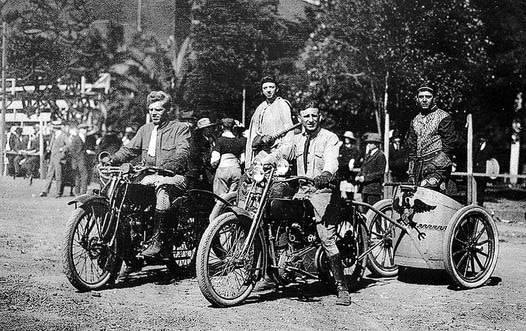

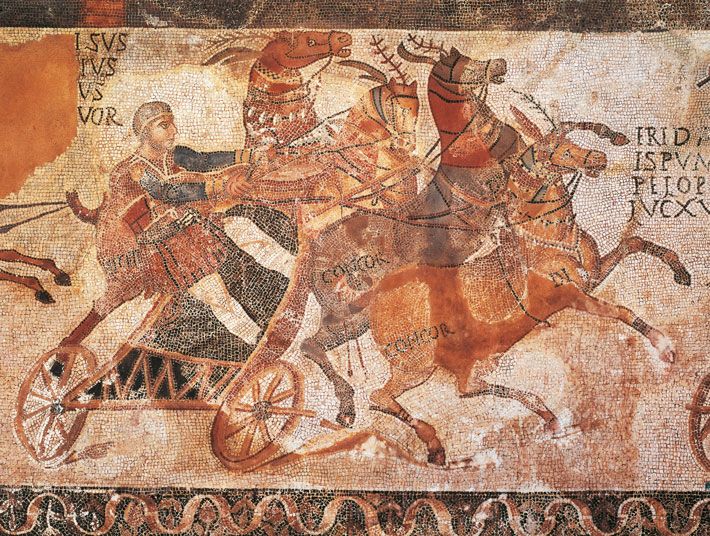

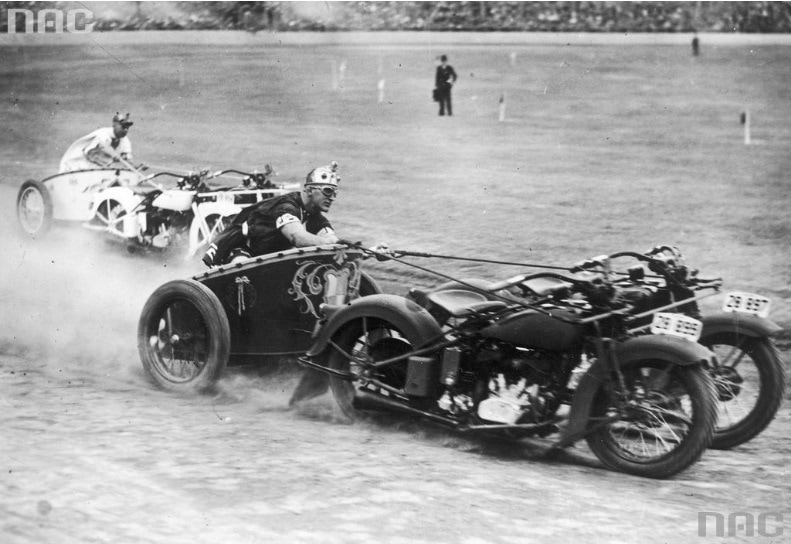

Elsewhere in California, an Italian poet’s work was scrutinized for treachery, and a father was hauled off by the FBI, leaving his wife and ten children without a breadwinner for four months. In New York, an Italian opera singer was thrown in prison without charge and just as unceremoniously released. Hundreds of Italian mariners who had been stranded in U.S. waters by the start of the war were loaded into Army trucks and hauled to an internment camp in Missoula, Montana, where some would remain for years. It was a distinctly American story, revealing the immigration system’s xenophobic through line. Poverty-stricken immigrants who were hated one day were approved of the next, only to be replaced by another allegedly dangerous immigrant group, all under the guise of national security. As beloved as Italian cuisine, sports cars, and fashion are on our shores today, things were different during the first half of the 20th century, especially during WWII.... CLICK HERE TO READ MORE...  "Engines" were small at first - a Half-Horsepower (Donkey) powered cart "Engines" were small at first - a Half-Horsepower (Donkey) powered cart No one really knows when chariot racing started, but the Greeks had chariot races during the first millennium BC and made the races part of the Ancient Olympics in 680 BC. Of course, chariots themselves were in use 4000 years ago. The most important development was a wheel with spokes. Before spokes, wheels were made from solid slabs of wood or thick shaped planks--both added weight before the cargo was even placed into the cart. Carts being pulled by animals--mostly oxen--were in use as early as 6000 years ago... but having an oxen as your main engine was very low torque--like a Mac truck. "Engines" improved slowly... at first a donkey or even a goat... sort of like early Model-T Ford runabouts. Then higher horsepower came in the form of mules and horses, one horsepower to start. The first chariots were used as delivery and work vehicles.  This car just wasn't fast enough to avoid the Law This car just wasn't fast enough to avoid the Law The history of NASCAR racing started with delivery vehicles, too. During the period of Prohibition in the 1920s, a bunch of backwoods good ol' boys smuggled liquor in from Canada or bootlegged whiskey (moonshine) from the tobacco fields of Georgia through to Chicago, New York and other big cities. Especially in the deep South, illegal booze was transported with with stock cars... they needed to look like every other car so as not to attract much attention. But special equipment was needed for the task at hand: heavy shocks and springs were added for the weighty loads of filled bottles and jars, and for smoothing the ride when driving fast on bumpy, unpaved roads; a high-powered engine was needed to deliver their booty quickly and to leave chasing authorities in the dust. High performance stock cars were born when Federal agents took chase... You can imagine that chariots started out also as "stock" units, with additions and modifications needed to accomplish their task. Adding a horse in place of a goat (more horsepower--literally) meant goods could make it to market faster and beat the competition. Perhaps this is where chariot racing started... two lemon growers meeting on the road and trying to beat each other to market. I'm certain that Greek and Roman officials taxed wine heavily, giving the ancient wine producer reason to race their "special" supply of wines past tax collectors to their regular clientele. Up until the 1st century AD, chariots were also used in the military. Racing to overcome the enemy, or perhaps betting on who would get to the battlefield first, might have also planted the seed of chariot racing. Special performance equipment on chariots continued to advance. In Ancient Rome, a two horse chariot was called a biga, a three horse chariot was a triga, and a supercharged, four horse power chariot was called a quadriga. Hey, they all sound like great names for modern car models! Vroom, Vroom! The horse chariot was a fast and lightweight vehicle and was indeed Spartan inside... again, like a NASCAR vehicle. There was barely a floorboard, no windows, and a waist-high guard at the front and sides. It must have been as uncomfortable a ride as what NASCAR race drivers have to put up with. Unlike other Olympic events, charioteers in Greek races did not perform their sport in the nude. Like NASCAR drivers, they wore safety gear: The clothing was itself their safety gear... a sleeved garment called a xystis went down to the ankles and had a belt fastened at the waist. Two criss-crossed straps across the back prevented the xystis from filling up with air during the race. Roman charioteers wore more protective gear--perhaps because most were not slaves, but paid professionals. They word helmets, leg guards, body armor or chain mail and wrapped the reins around their forearms. In case of a crash they would be dragged along the ground and could be killed, so one final bit of protection was to carry a falx (a curved knife), used to cut their reins away in an emergency. When official chariot racing became popular, it wasn't the driver who owned the horses and chariot. Just as in NASCAR, there were team owners. In 416 BC, the Athenian general Alcibiades had seven chariots in the race, and came in first, second, and fourth. He obviously hired drivers to be at the wheel... er... at the reigns, that is. Unlike NASCAR drivers who some might argue are slaves to their sponsors, many drivers (who remain unknown to this day) were actual slaves. The racetrack--called a Hippodrome (Greek) or a Circus (Roman)--was oval with tight turns on either end, just like (getting tired of saying this) NASCAR courses. Chariots went around and around, counterclockwise, with nothing but left turns (sound familiar?) These turns were deadly and many crashes occurred. Although running into an opponent with the intent to cause a crash was strictly forbidden--it was tolerated because it made the crowds go wild. The ancient Greek and Roman spectators loved crashes, as they loved any blood sports of the day. Modern NASCAR spectators are conflicted--as loyal fans, they don't want to see their favorite drivers injured or killed, but just as the ancient spectators, when a crash happens, they get an adrenaline rush and a thrill they'll remember for a lifetime. Chariot races began with a procession into the hippodrome, while a herald announced the names of the drivers and owners--he had to be a very loud public speaker, indeed. NASCAR tracks have lots of loudspeakers. On the flip side, aside from cheering crowds and the sound of horses hooves on a dirt track and the occasional cracking of wood during a crash, a chariot race must have been a quiet affair when compared to the off-the-scale high decibel assault the NASCAR fan must endure as car after car go revving by for hours on end at up to 200 miles per hour! The smells were very different too... horse poop versus the exhaust from 110 octane fuel and burning rubber...  Ready to throw down the "Mappa" for the race to start Ready to throw down the "Mappa" for the race to start A race called the tethrippon (in Greek regions) had twelve laps around the track, while Roman races often had 7 laps to allow more races in a single day for betting--Romans and gambling went together more than in the Greek culture. Even more interesting is the way the races were started. In the same way that NASCAR uses a pace car to get cars up to starting speed before checkered flag starts the race, the Ancients used mechanical devices to accomplish a similar task for a rolling--or rather--galloping start. The starting gates were lowered and staggered in a way so the chariots on the outside lanes began the race earlier than those on the inside. The race only began when each chariot was lined up next to each other--"keeping pace". Chariots in the outside lanes would be moving faster than the ones on the inner lanes. While flags are used in modern auto racing, mechanical devices shaped like eagles and dolphins were raised to start the race. Dolphins were lowered with each successive lap. In Rome, often the Emperor himself would start the race by dropping a white cloth called a mappa. In the end, the winners were given their awards right away. An olive wreath was placed on their head. In the Roman Empire there would be cash awards or possibly a gift of a slave for the charioteer. Fame was also part of the game, as is the case today. Scorpus, a celebrated driver won over 2000 races before being killed in a collision at the ripe age of 27. Most charioteers had a short life expectancy. The most famous driver was Gaius Appuleius Diocles who won 1,462 out of 4,257 races. When Diocles retired at the age of 42 (after 24 years) his career winnings 35,863,120 sesterces--approximately 15 billion dollars today--making him the highest paid sports star in human history. A couple of more interesting differences: Women weren't permitted at the races as they are today; and while today's largest NASCAR racetracks hold under 150,000 spectators, the Circus Maximus in Rome held 250,000! Gentlemen, start your... er... feed your horses! Go! --Jerry Finzi Copyright 2017, Jerry Finzi/Grand Voyage Italy - All Rights Reserved

Names can tell a lot when researching our Italian roots. But there are some names which tell a sadder tale back several generations or so. Orphans and foundlings in Italy were given special names. This list includes the most common surnames used.

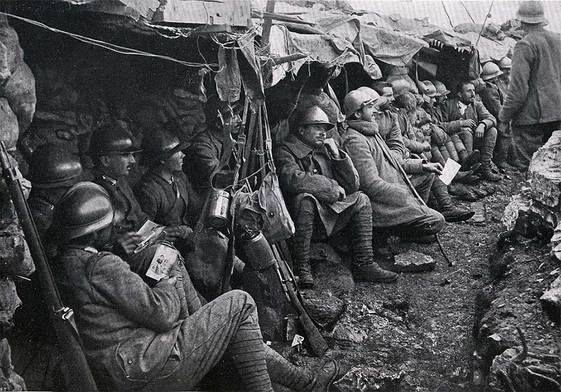

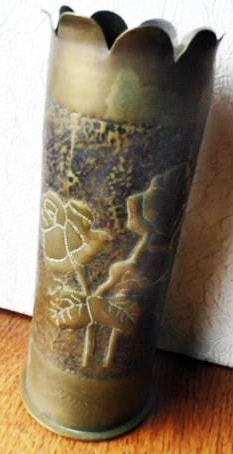

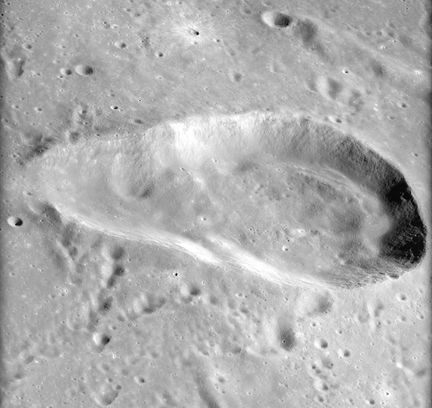

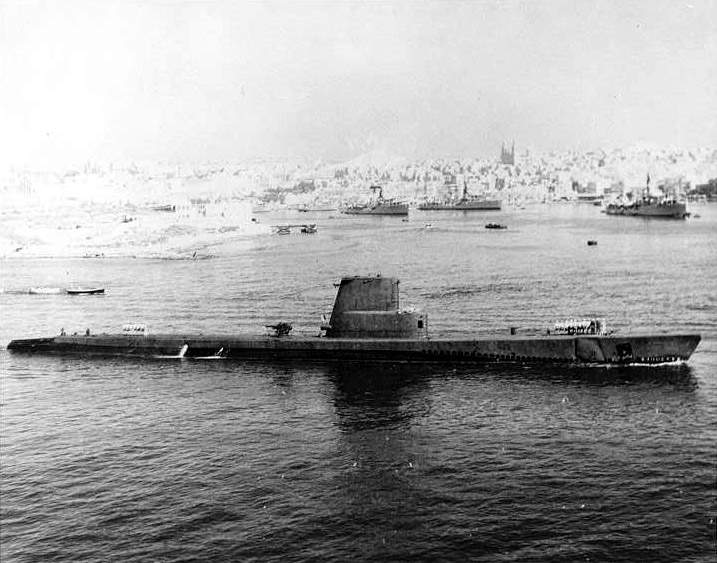

Some means of names are pretty obvious: Bastardo... for bastard. Della Femina for From a Woman. Dell'Amore means From Love. All are a testament to those who came before and the trials they must have gone through to get through troubled times of war or poverty or disgrace. Many suffered through the horrors of war or famine. Anyone bearing these Italian surnames should be proud of what their fore-bearers went through to give life to their children and their children's children. Although these names do have a high probability of being rooted in an ancestor being orphaned, there are exceptions to this. Amodio (Love God), Arfanetti (Orphan), Armandonada (Donated by Hand) Bardotti (The sterile hybrid offspring of a male horse and a female donkey) Bastardo (Bastard), Circoncisi (Circumcised) Colombini (Little Dove), Dati (from you) Circoncisi (Circumcised) De Alteriis (Changling), De Angelis (From Angels) Della Donna (From a Lady), Della Femmina (from a Female) De Domo Magna ("Of the Ospizio" ,of the Hospital or Hospice) Degli Esposti (Abandoned) Della Scala (Name assigned by foundling home in Sienna) Della Fortuna (from Luck), Della Gioia (From Joy), Della Stella (From a Star) Della Casagrande (of the Hospital/Orphanage) Dell 'Amore (from Love), Dell'Orfano (the Orphan) Del Gaudio (of Grace & Goodness), Diodata (God Diven) D'Amore (Love), D'Ignoto (from Unknown), Diotallevi (God Raised You) Esposto, Esposito, Esposuto (Lost) Fortuna (Luck), Ignotis (Unknown), Incerto (Uncertain) Incognito (Unknown) Innocenti, Innocentini (The Lost Ones) Mulo (Mule), Naturale (Natural/Careless) Nocenti, Nocentini (Little Innocent), Ospizio (Foundling Home) Palma (when child is abandoned on Palm Sunday) Proietti (Thrown away - also, Projetti, Projetto, assigned by an ospizio in Rome) Ritrovato (Discovered) Sposito (Lost), Spurio (Illegitimate) Stellato (The Stars), Trovatello, Trovato (Foundling) Ventura, Venturini (Angels, Little Angels) Legislation passed in 1928 outlawed the practice of assigning orphans surnames indicating their illegitimacy or abandonment, but surnames of some sort still had to be given to these children. These were sometimes the surnames of royal and noble families, but more often they were geographical in nature or alluded to the day, month or season of the child's birth (i.e. Sabato, Maggio, Primavera and so forth). --Jerry Finzi  Artillery shells -an abundant source for trench art Artillery shells -an abundant source for trench art The Great War, as it is called, was a dramatic shift in the way war was waged... with the introduction of tanks, churning up the land as they mowed down anything, and anyone--in their way. Both tanks and cannons pulled on carts meant there would be shells remaining... countless numbers of them seemed to become part of the landscape of war, along with the barbed wire and trenches filled with men and vermin. Italian soldiers were often stuck in the trenches for extended periods, and somehow, from an urge to ease the boredom or simply forget about the horror and fear, they used the jetsam of the battlefield to create trench art.  Shell art (not the seashell type) is one of the most famous types produced in wartime. Soldiers hammered intricate designs into the casings of artillery shells. Smaller ones were decorated and carried in pockets, often made into cigarette lighters. The larger were turned into vases, bowls, ash trays, or cachepots and taken home after the war was over. The soldiers would use whatever tools they had available, creating a range of designs, often dating and naming the battles and victories they took part in, or simply adorned with flowers to please a loved one waiting back at home. When you look at the beautiful designs on these pieces, it's a wonder that these men crafted them while the world around them was in chaos. --Jerry Finzi  Evangelista Torricelli was born Oct. 15, 1608 in Faenza, Romagna. He was an Italian physicist and mathematician who invented the barometer, a device that measures atmospheric pressure, commonly used in forecasting changes in the weather. The catalyst for inventing the barometer was spurred on my a suggestion by Galileo that Torricelli use mercury in place of water for his vacuum experiments. After reading his papers in 1641, Galileo invited Torricelli to Florence, where he became the aging astronomer's secretary and assistant during the last three months of Galileo’s life. After Galileo's death, Torricelli was appointed as his successor as professor of mathematics at the Florentine Academy. Two years later, pursuing the suggestion by Galileo, he filled a glass tube 4 feet (1.2 m) long with mercury and inverted the tube into a dish. He observed that some of the mercury did not flow out and that the space above the mercury in the tube was a vacuum. Torricelli became the first man to create a sustained vacuum. His observations proved that the variation of the height of the mercury from day to day was caused by changes in atmospheric pressure. He never published his findings, however, because he was too deeply involved in the study of pure mathematics. Since atmospheric pressure also changes with altitude, Torricelli's barometer also could be used as an altimeter. Torricelli died Oct. 25, 1647 in Florence at a mere 39 years old. As a further honor, Torricelli had both a crater on the moon and a submarine named after him... Play the video to see how Torricelli's experiment worked.

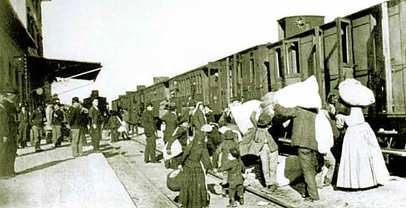

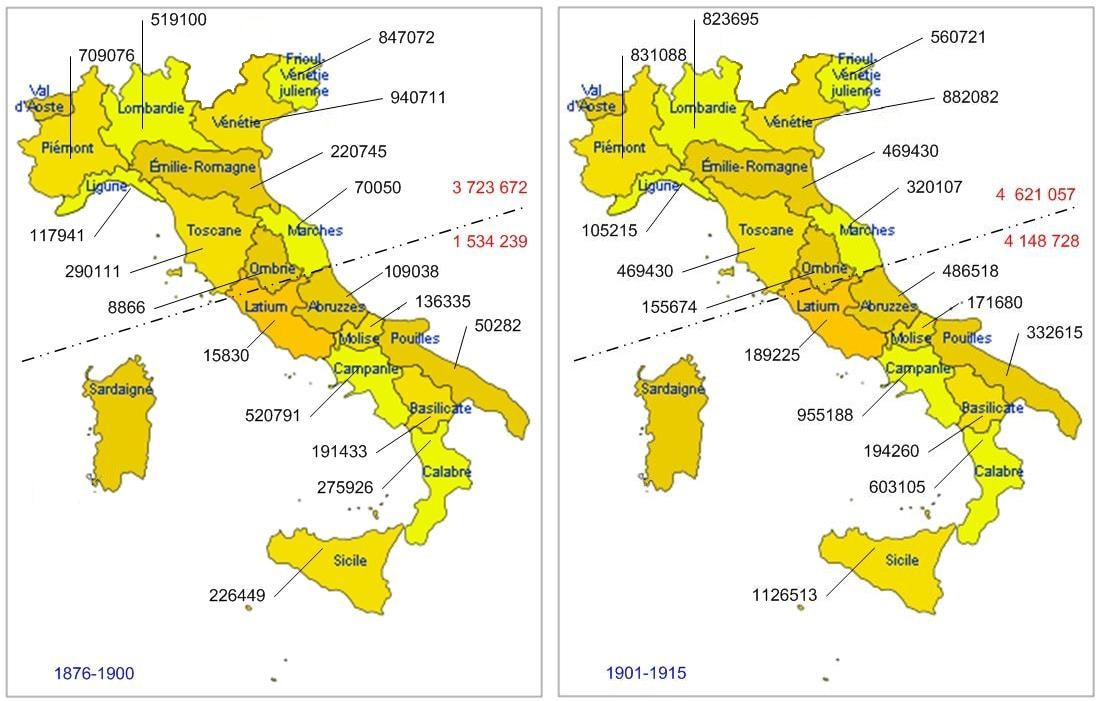

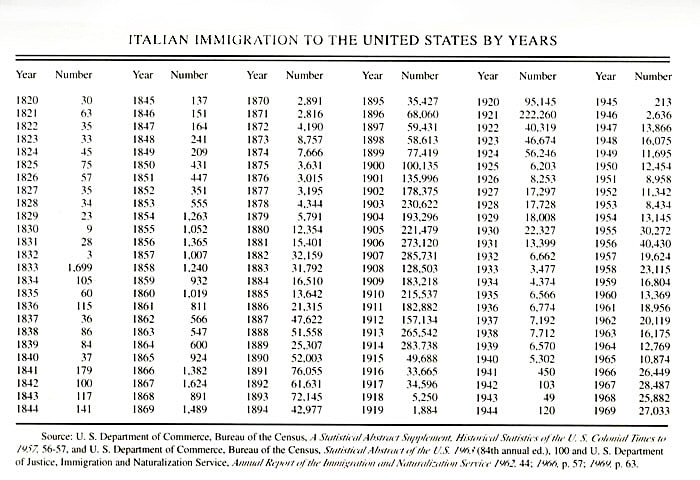

Packed like sardines... Coming to America Packed like sardines... Coming to America The Many Reasons for Coming to America Poverty was the main motivation for an Italian leaving his family and home and putting up with the hardships of traveling to America. In 1898, widespread "bread riots" plagued all of Italy, with people protesting the lack of jobs and the sudden increase in the price of wheat and bread. Other motivators were the constant political strife and the dream to return to Italy with enough money to buy land and improve their lives. Fully 80% of Italians were farmers and couldn't afford modern farming equipment to better their lives. Rural Italians lived in harsh conditions, residing in one-room houses with no plumbing or privacy. In addition, many peasants were isolated due to a lack of roads in Italy.  It was difficult to feed such a large family in rural Italy It was difficult to feed such a large family in rural Italy Most Italians didn't own land, so they were indebted to landlords, who charged high rents and took a portion of their crops. Higher wages in America--as often falsely advertised by many flyers produced by steamship companies--proved to be an attractive draw. AN Italian contadino who farmed year-round might earn 16-30 cents per day in Italy. A carpenter in Italy would receive 30 cents to $1.40 per day, making a 6-day week’s pay $1.80 to $8.40. In America, a carpenter who worked a 56-hour week would earn $18. Farmers faced even further reasons to immigrate. Besides falling wheat prices, fruit and wine prices were also falling. The phylloxera virus destroyed nearly every grape vine used to produce wine. America was envisioned as a place of opportunity, with abundant land, high wages, lower taxes--and at the time--no military draft. Yes, one more reason why many Italian men wanted to leave Italy... to escape conscription into the military. But still, many wanted only to go to America, earn money and return to buy their own land. Political hardship was also a factor in motivating immigration. Beginning in 1860, la Guerra dei Contadini del Sud (the Southern Peasants War) began. This was an uprising to resist the changes that the North was forcing on the Southern provinces with the Unification. Led by mostly brigands (many of who had previously had the support of contadini), this was a type of "social banditism" who were rebelling in order to retain their small sphere of power and wealth in their rural areas. The poor contadini were caught suddenly in the cross fire. Later in the 1870s, the government took measures to repress political views such as anarchy and socialism. Many Italians came to the United States to escape political policies and warring factions.  Taking a train to an Italian port city Taking a train to an Italian port city Italian immigrants to the United States from 1890 onward became a part of what is known as “New Immigration,” which is the third and largest wave of immigration from Europe and consisted of Slavs, Jews, and Italians. This “New Immigration” was a major change from the “Old Immigration” which consisted of Germans, Irish, British, and Scandinavians and occurred earlier in the 19th century. Between 1900 and 1915, 3 million Italians immigrated to America, which was the largest nationality of “new immigrants.” These immigrants, a mix of both artisans and peasants, came from all regions of Italy, but the largest numbers were from the mezzogiorno--Southern Italy. Between 1876 and 1930, out of the 5 million immigrants who came to the United States, fully 80% were from the South, representing such regions as Calabria, Campania, Abruzzi, Molise, Apulia and Sicily. The majority (2/3 of the immigrant population) were farm laborers or laborers, or contadini, as noted on the ship manifests when arriving at Ellis Island. The laborers were mostly agricultural and did not have much experience in industry such as mining and textiles. The laborers who did work in industry had come from textile factories in Piedmont and Tuscany and mines in Umbria and Sicily. Though the majority of Italian immigrants were laborers, a small population of craftsmen also immigrated to the United States. They comprised less than 20% of all Italian immigrants and enjoyed a higher status than that of the contadini. The majority of craftsmen were from the South and could read and write; they included carpenters, brick layers, masons, tailors, and barbers. The first wave of Italian immigration began in the 1860s after the Unification of Italy. By 1914, the number of Italians immigrating to the United States reached it's peak at over 280,000 making the journey to America. Since there was a larger population and higher skilled laborers (such as miners) in the industrial northern Italian provinces, a higher number emigrated from the North. But even though the South had a sparser population with less labor skills, more per capita came from these southern regions. In fact, by 1915, the number of emigrants from the South nearly matched those coming from the North.  Due to the large numbers of Italian immigrants, Italians became a vital component of the organized labor supply in America. They comprised a large segment of the following three labor forces: mining, textiles, and clothing manufacturing. In fact, Italians were the largest immigrant population to work in the mines. In 1910, 20,000 Italians were employed in mills in Massachusetts and Rhode Island. An interesting feature of Italian immigrants to the United States between 1901 and 1920 was the high percentage that returned to Italy after they had earned money in the United States. About 50% of Italians repatriated, which can be interpreted as many having trouble assimilating into the American way of life. Some of this can be blamed on the blatant racist views toward Italians and refusal to hire them for better paying jobs. In the large cities, tenements were essentially slums. If an immigrant couldn't get a decent living wage, they might reconsider trying to raise their family in America. Because Italian immigrants tended to be gregarious--often clustering together in "Little Italys", often they didn't feel there was a need to learn English, another factor in not being able to secure better paying jobs. Many might have fallen into the trap of getting housing or jobs through a padrone, a boss and middleman between the immigrants and American employers. The padrone was an immigrant from Italy who had been living in America for a while. He at first might seem helpful in providing lodging, functioning as safe "bankers" or money changers (often short changing), and found work for the immigrants (albeit, for a percentage of their earnings). Often, they would get the work that they could do in the apartments they rented to them... making silk flowers, rolling cigars, sewing, etc. After a few years of paying a percentage of their salaries to these padrone, many immigrants got discouraged enough to return to the homeland. At best, these situations became indentured servitude, at worst slavery. Child labor was also a product of these padrone, filling sweat shop factories with children as young as 10 years old. Prejudice Rears its Ugly Head Both immigrant contadini and those with skills faced economic as well as ethnic prejudices upon entering the labor force in America. The poor economy caused hostility toward Italians and many were labeled as strikebreakers and wage cutters from 1870 onward. American workers already feared the new mechanization in factories was the cause of taking away their jobs. Job bosses used Italians to fill their jobs as scabs during labor strikes. Prejudices were especially aimed at (as perceived) darker skinned Southern Italians who became scabs during strikes in construction, railroad, mining, long shoring, and industry. The Italian workers were called derogatory names such as:

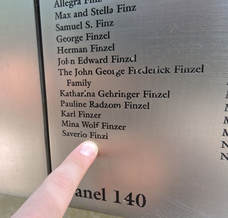

Italians were the only workers to work along side black people and employers preferred Slovaks and Poles to Italians. At the time, it was said that "railroad superintendents ranked Southern Italians last because of their small stature and lack of strength”. In the mining industry especially there was an ethnic hierarchy: English-speaking workers held the skilled and supervisory positions while the Italians were hired as laborers, loaders, and pick miners. It was not until the 1920s that Italians became more integrated into the American working class, regardless of whether or not they spoke English. More immigrants started to work at semi-skilled jobs in factories as well as skilled positions but one-third of the population remained unskilled. In trade unions, meetings were held in English and Italians were not elected to official positions.  Dad's name on the Ellis Island wall - Saverio Finzi Dad's name on the Ellis Island wall - Saverio Finzi My Grandfather, Sergio Finzi had made two preliminary Voyages across the Atlantic trying to establish connections and work so he could bring his wife and children over. He was a tailor, a skill he brought with him from Molfetta. They were poor. My father told of not having enough coal or wood to fire up their kitchen stove--the only heat in winter. He said he and his brother walked the railroad tracks to pick up scraps of coal fallen from passing trains. They left school in the fourth grade to help the his familia scrape a living from their new home. Many Italian immigrants suffered--and endured. We are all proof if this fact. Italian immigrants--as many immigrants from other lands--help build this country. They helped defend it. They assimilated. They became citizens. Paid taxes. Sent their kids to school. And here we are... over 100 years later and many in our country are still ambivalent or even dead against immigrants. Have we really lost sight of the fact that unless we have 100% Native American blood running through our veins, that we all are descended from immigrants? Starting in 1888, photographer Jacob Riis, a Danish immigrant, in an attempt to call attention to the suffering of immigrants, photographed the Manhattan tenement slums where Italian (and other) immigrants were living in squalor. He was followed by Lewis Hines, who photographed not only the immigrants and slums but the children who were the most helpless victims of this inflicted poverty. Enjoy the slide show... and try to remember the hardships our fore-bearers went through to get us where we are today... --Jerry Finzi On our modern Julian calendar, March is the third month of the year, but to ancient Romans, Martius (as it was called) was the first month of each new year. It makes sense when you think about it. Right now in Italy, the flowers are blooming all over the place. Things are growing, the weather is warm again and it makes sense to think of Spring as the beginning--the birth--of a new year. The Romans celebrated holidays from the first through the Ides of March (on the 15th) to bring in their New Year. The most important celebration on the Ides was to the god Jupiter, the supreme deity, but also to Anna Perenna, the goddess of the year itself. Anna Perenna was more popular with the plebeians of Rome who drank, played games and had picnics. Later, in Imperial Rome, the Ides began a week long celebration for several various festivals. The so called "Ides" of a given month refer to the midpoint of a month, for some months (like March) falling on the 16th, and on others falling on the 13th day--all governed by the phases of the moon. The Ides on the ancient Roman calendar was on the new year's first new moon. The Romans didn't use day numbers, but counted backwards from given points in the month... the Nones (5th or 7th, depending on the length of the month), the Ides (13th or 15th), and the Kalends (1st of the following month). Of course, we all know that in modern times, the Ides of March is the day that Julius Caesar was assassinated in 44 BC. Shakespeare tells the tale in his classical play Julius Caesar... Caesar was stabbed to death by a crowd of his opponents, with Brutus and Cassius at the lead. A seer foretold that Caesar would come to an end on the Ides, but when the day came he saw the seer on the street and laughed in his face, saying that nothing bad had happened, but the seer answered back, "...Yet".  Recently, researchers think they have found the exact location of where Julius was stabbed 23 times by the group of senators... at the Largo di Torre Argentina, in the center of Rome not far from the Pantheon, known nowadays to tourists and Romans alike for the tram station adjacent to the site and all the feral cats that live among the ruins. Ancient texts always claimed that Caesar was killed in the Curia of Pompey, a theater at the site, but until recently no archeological evidence could be found. In 2012 a large concrete marker was found which was erected as a monument to Caesar by his loyal followers after his death... All those cats seem to be wandering and waiting for Caesars return... You can hear their call... "miao, miao... miao..." Oh, I almost forgot... Felix Annus Novus! (That's Happy New Year in Latin.) --Jerry Finzi You can also follow Grand Voyage Italy on: Google+ StumbleUpon Tumblr |

Archives

May 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed